The beauty of Arabic calligraphy that adorns the grand mosques in Dubai and Delhi, in Agra and Surakarta, in Kuching and Kuala Lumpur, fascinates me. But I know little about the history of khat, even though they are emblazoned on our coat of arms and printed on the ringgit notes.

Little knowledge does cause confusion – and protests - with sensitive controversies such as the ongoing khat kerfuffle. Hence, I researched the different interpretations of the ‘problem’, starting with KiniGuide’s comprehensive explanation.

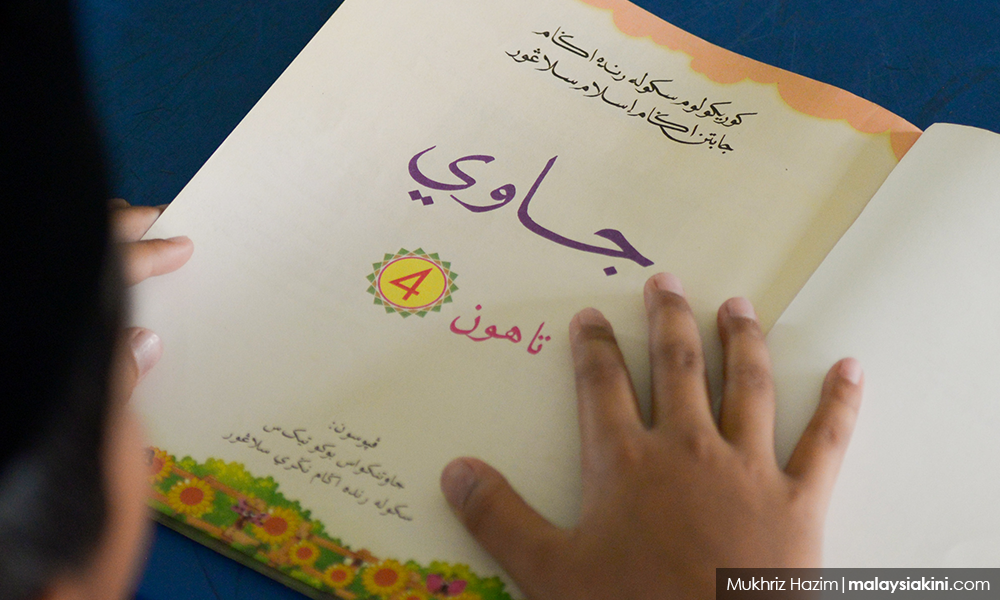

My premise is simple. The educational benefits of children learning khat, or any new language and script art, far outweigh the imagined fear of the adults in losing their non-Malay heritage, their language, their identity, and so forth.

Reactions to the khat issue are unsurprisingly fractious. Because the teaching of khat is seen as a racially driven ideological issue, an Islamic imposition, the reactions are likewise racial, ideological and polarised. We shouldn’t be surprised at the resultant politics given the racialised environment we live in today.

However, if teaching khat were perceived as simply teaching a third or fourth language in primary schools, one would look at the principles of multilingual pedagogy and its benefits, and clarification of its learning outcomes.

Learning khat or Jawi piecemeal without definitive objectives and learning outcomes simply muddies the rationale and defeats the purpose of introducing khat in the first place.

This kerfuffle certainly falls at the feet of the multilingual education minister, MaszleeMalik (above), who is of Hakka-Chinese and Malay descent, who speaks “fluent Arabic and English, moderate French, German, simple Mandarin and Hokkien”.

The 44-year-old minister’s execution of the khat idea may simply be what falls within his sphere of internal coherence. Indeed, “we are a sum total of what we have learned from all who have taught us, both great and small.”

According to Wikipedia, Maszlee had taught at the International Islamic University Malaysia, studied Islam and the Middle East. His doctoral thesis at Durham University is titled "Constructing the Architectonics and Formulating the Articulation of Islamic Governance: A Discursive Attempt in Islamic Epistemology”.

Some analysts attribute the ‘khat’ kerfuffle to the perceivably unpopular minister’s lack of clarity in explaining the rationale for including khat as part of the Malay language syllabus.

Non-Malay educationists interpret the proposal as an extension of Islamic ideology which, according to one of the academics that drafted the curriculum, is grossly mistaken.

Another article attributes the ‘fuss’ to the intrusion of ethnicity, religion and ideology into the Malaysian education system.

In questioning the proposal, the author cautions that "schools have to be safeguarded from political and religious influence, be it Jawi (regarded as a language) or khat. It is still closely associated with the glory of Islam and is a scripture closely related to Islamic teaching and the Quran.”

A well-researched article, however, dispels the public ignorance about Jawi with reference to the evolution of great languages and scripts to what they are today, for instance, the Romanisation of old Chinese characters to pinyin for easier articulation and usage.

The Chinese author sums up the thinking of Malaysians who value the wisdom of learning a new language: “Islam, as a religion, has been around for 1,400 years, yet there are still Christians among Arabs (who) are still using the same Arabic script as their Muslim peers to write their language … claiming that learning Jawi would make a non-Muslim convert to Islam is as ridiculous as claiming that using Latin script would make one convert to Christianity.”

A former ambassador who calls for the khat proposal to be reconsidered and the education system reformed to be more inclusive (and progressive), notes: “When will our policymakers learn to respect Malaysia’s minorities enough to consult with them and seek consensus, instead of simply foisting controversial policies on an already sullen and suspicious population? Is it ignorance or arrogance?”

A fellow columnist makes similar arguments about giving parents and their children the option of deciding whether appreciating khat and writing Jawi is relevant to their learning needs in the cyber age.

Which brings me to a related critical issue – the issue of implementing practical measures to improve the standards of education and language teaching at all levels.

Ultimately, it is less about the medium of instruction – nor learning khat or wearing black shoes - but more about explaining to parents the rationale of multilingual pedagogy and affirming the nobility of the teaching profession.

Developing cognitive and emotional intelligence in primary school children is only possible if we have teachers who are well trained in innovative pedagogy and critical or computational thinking. Entrance requirements for teaching programmes should be raised to ensure that applicants possess numeracy and literacy skills, and certainly high proficiency in the English language.

Retain the talented teachers who are demonstrably innovative in their teaching methods to mentor junior teachers. This means higher investments in teachers are needed to raise the prestige of the teaching profession.

While every Malaysian should master the national language, it should not diminish the importance of English as the medium of learning for the simple reason that English is the main language used online, in spite of Google translate, to access the world’s literature, philosophies and research across all fields.

English was the medium of instruction during my time. I remember the government abolished English for Malay as the teaching language in the 70s to unite the rakyat. Inter-racial mistrust, however, lingers to this day.

A national language or learning khat is less a ‘Malaysianising’ factor than the rule of law, good governance, fair access to economic opportunities, shared life goals, sincere inter-racial engagement, and, as the humanist would say, our duty to do right by each other.

ERIC LOO is a Senior Fellow (Journalism) at the School of the Arts, English & Media, Faculty of Law, Humanities & Arts, University of Wollongong. He is also the founding editor of Asia Pacific Media Educator. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.