Covid-19 has infected more than two million people in the country since it was first discovered in Malaysia in January 2020.

The spread of the disease has become more complicated and difficult to manage in the past year with the emergence of variants that are more transmissible and infectious.

However, a large percentage of Malaysia's population of about 32 million has been fully vaccinated since the nationwide vaccination rollout in February 2021.

Similar to the Covid-19 pandemic, the spread of misinformation and disinformation related to the disease and tonnes of conspiracy theories have appeared all over social media.

The digital space has created an infodemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined an infodemic as “too much information including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak”.

Misinformation and disinformation of Covid-19 can cause a lot of confusion and dangerous misleading information that can influence risk-taking behaviours to harm public health.

They can also cause mistrust in health authorities and the media, as well as undermine the public health response to mitigate and manage the Covid-19 pandemic.

This report shall attempt to understand better and delve deeper into the impacts of the infodemic related to Covid-19 affecting newsrooms in Malaysia over the past two years and understanding the methods adopted by newsrooms to address misinformation/disinformation.

Since 2020, the Perikatan Nasional administration pledged to take on misinformation and disinformation more seriously.

To tackle the spread of misleading information since the rollout of the national vaccination programme in February 2021, the government imposed a special emergency ordinance to combat the infodemic.

Anyone charged for spreading “fake news” faced a maximum fine of RM100,000 and up to three years in prison. The ordinance makes it a crime for anyone who “creates, offers, publishes, prints, distributes, circulates, or disseminates any fake news” that would cause fear in the public.

Although the Anti-Fake News Act 2018 was repealed in 2019 during Pakatan Harapan’s administration, the new emergency ordinance was established on top of existing laws that can be used against misinformation and disinformation.

Those laws include the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 and the archaic Sedition Act 1948.

More complicated information gatekeeping

Leslie Lau, managing editor of Malay Mail admitted that the Covid-19 infodemic has made it more challenging for journalists and editors in terms of gatekeeping information with fact-checking and verification.

“I think generally, most of us at Malay Mail, we will stick to the official sources, i.e. whether the WHO or the Health Ministry. It was only last year, it wasn't that much of a problem, it is mostly this year.

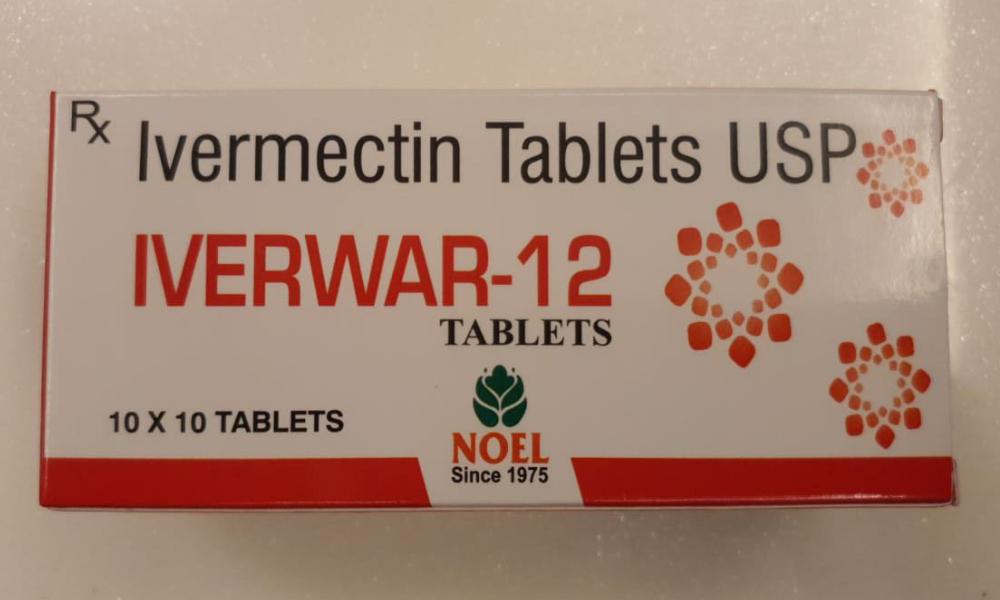

“Last year I think there was... you could sense more faith in the system but this year particularly the anti-vax and ivermectin lobbyists have grown. I'm glad for one thing that among my colleagues in Malay Mail, none of us is anti-vaxxers and that definitely helps,” Lau said.

He added that despite pressure from some readers to publish alternative treatments of Covid-19, Malay Mail decided that while freedom of speech is acknowledged, letters that came from readers or lobby groups for ivermectin would not be published in view of the public good.

During the special parliamentary session in July 2021, MPs from Pakatan Harapan were asking the Health Ministry to allow ivermectin as an off-label use to treat Covid-19.

A clinical trial on the use of the anti-parasitic drug was initiated by Malaysia's Health Ministry and the Institute for Clinical Research (ICR).

“We did cover minimally these ivermectin lobbyists but definitely from the standpoint of the Health Ministry’s response to it, rather than being seen as promoting or helping them.

“My feeling was that a lot of these guys were just desperate. I received phone calls from people I least expected to promote ivermectin and say why are we so negative about it or not covering it. I think in a way, it wasn't difficult. This is unproven, this is not science. It was just nonsense,” Lau said.

Meanwhile, Hussamuddin Yaacub, owner and managing editor of Malay-language newspaper Sinar Harian said their policy is to avoid breaking news.

He said as most of their ad revenue comes from their print version, they don't have to compete with other digital outlets to publish news the fastest.

“We have to verify the stories, and that is why now for Sinar Harian, we are more cautious with this.

“I think in a way this is also positive, we let other people make blunders. If you want to see the truth, wait for Sinar's reports,” he said.

Hussamuddin explained that print media organisations were conditioned in an environment where the industry was governed by the Home Ministry for many years.

Under the Printing, Press and Publications Act 1984, the Home Ministry and its minister have the power to revoke or award printing licenses to media companies.

He also said print media have operated for so long knowing that the Home Ministry may call up their writers, editors, printers, or distributors for questioning if there were to be any misreporting or sensitive reports.

This, he said, led to their policy of exercising more caution in dealing with misinformation and disinformation.

“We have been trained to support the government of the day so we have to refer to the official source. For example, if you see the editorial stand of Sinar on anti-vaccines, from day one, we tried to avoid controversies.

“We build the company to this level and we should not make mistakes. We are a bit conservative. We don't really go for number one, because to be number one, you have to break every rule. The fear factor governs us. The company's reputation is supreme,” Hussamuddin stressed.

Limited access of information for journalists

The Covid-19 pandemic in Malaysia saw at least three different implementations of nationwide lockdowns and restricted movements of people to curb the spread of the infection.

This situation complicated the work of journalists and media organisations to verify queries and information related to Covid-19.

Ng Ling Fong, the managing editor of Malaysiakini, said there was a lack of transparency and access to relevant authorities like the Health Ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office during the previous Perikatan Nasional administration led by former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin, which only allowed selected media organisations particularly official government media to access ministers and ministries.

“When there are fewer press conferences, we will have less opportunity to meet, to get information, to clarify certain issues especially on Covid-19 related information with the person in charge from the ministries.

“Although some may argue that we can still contact them through phone calls or emails, it's up to them whether they want to reply or not. They will pick and choose the information they want to reveal to the media.

“Unless you ask during a press conference, the journalists can still continue to pressure them to answer should they try to avoid it. We noticed that the frequency of press conferences held by the Health Ministry started to move from daily to weekly, it has become less and less (frequent),” Ng said.

In the beginning, Ng mentioned that government press conferences related to Covid-19 were open to all and the press were allowed to ask questions freely.

Soon after that, the press had to submit the questions earlier to the person-in-charge in the Health Ministry to choose the questions to be asked during the press conference.

Malaysiakini has also published a series of explainer stories called “KiniGuide” in an attempt to provide more in-depth reporting and descriptive explainer articles focusing on the Covid-19 pandemic and the vaccines.

The articles were also translated into Malay, English, Mandarin, and Tamil.

Malay Mail’s Leslie Lau echoed the sentiments from Malaysiakini that the restrictions of movement during lockdowns made it more difficult for newsrooms and disrupted the process of news gathering in the midst of the pandemic.

He said the situation caused newsrooms to become more vulnerable to fake news.

“Sometimes when you let your guard down, you end up publishing news that is not quite accurate. This was the case even before Covid-19, but I think it has accelerated especially because of how news media companies are under tremendous financial strain.

“To give you an example, I saw on social media, people taking photos of homeless people in KL, and in normal situations, you would send reporters down there to find out whether it is true or not. Which I did, but they are difficult to find (due to movement restrictions),” Lau added.

He also said it was difficult to get access to people for interviews and the concern was to protect journalists from getting Covid-19.

Coupled with fewer reporters and having to work longer hours, Lau said such a scenario made it more difficult to keep track of what was happening on the ground.

“It's really difficult because editors do not have enough time to monitor (news) and we do not have enough resources to see what is happening out there.

“I think it is a tremendous strain but it presents a conundrum (of what) traditional journalism means.

“You need the time and space to work and find the real stories. Right now with the competition out there and the challenge of verifying these stories, it's really tough.” - Mkini

This article first appeared on mediamalaysia.my.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.