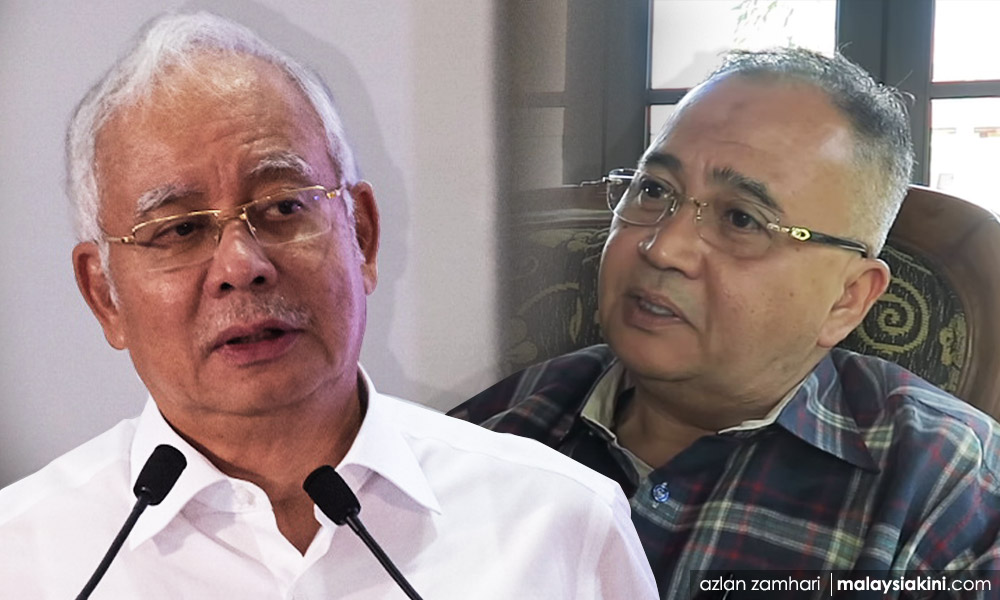

The news that former deputy prime minister Ghafar Baba's grandson, Zahid Mat Arif, from Bersatu is Pakatan Harapan’s choice to contest Umno president Najib Abdul Razak in Pekan enjoys a certain symbolism.

Bersatu has been mulling who best to take on Najib in the Razak family redoubt, and after sifting through a slew of potential nominees has settled on Zahid.

The choice possesses a certain symbolism, though it is doubtful that in these times of a dearth of historical consciousness among the people, enough of them would be aware of the antecedents that make Zahid an echo of times past.

It used to said that when Malaysia's second prime minister Abdul Razak Hussein (September 1970-January 1976), prime initiator of the raft of policies to uplift the Malays, wanted to see how some policy of his would go down with that demographic, he would skip round the table of the Umno supreme council meeting to ask for Ghafar's opinion.

To Razak, Ghafar was the Malay “Joe Public”.

If Ghafar felt good about a Malay-centric policy, Umno president and prime minister Razak would be certain his latest initiative on behalf of the Malays would have a good reception.

Ghafar Baba was regarded as the embodiment of the generic Malay person, such that a government wanting to court that demographic would have to reckon with Ghafar's opinions.

His schoolteacher beginnings had equipped him to be a listening post for sentiments on the Malay grapevine.

A costly refusal

Malaysia's first prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman (1957-70) wanted to send Ghafar, chief minister of Malacca for most of Tunku's premiership, to England to read for a degree, but Ghafar was not keen: Somebody with a good feel for the pulse in an occupation where you could be borne along on endless billows is apt to disdain a long pause to take in the academic round.

But Ghafar's refusal would cost him.

In early 1976, when newly-installed prime minister Hussein Onn, cast around for a deputy, Ghafar, as the senior-most Umno veep, was the safest choice to be deputy.

But Hussein, who wanted Umno supreme council member Ghazali Shafie as deputy, was told by the three party veeps – Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, Ghafar Baba and Dr Mahathir Mohamad – that adherence to tradition entailed a choice of one of them for the vacant No. 2 role.

A constrained Hussein then chose Mahathir, reckoning that Ghafar's lack of tertiary education disqualified him and that Razaleigh's youth (he was 39) was an encumbrance.

Nevertheless, Ghafar was appointed deputy prime minister when Musa Hitam resigned the post in February 1986, his lack of a tertiary qualification not then viewed as disabling, perhaps because then prime minister Mahathir was so dominant a head honcho, any deputy had to be a mere cipher rather than contender for top honours.

Even as a political nondescript, Ghafar did not lose his potency as a barometer of Malay sentiment, though rapid changes in the socioeconomic status of the Umno rank and file by the onset of the 1990s meant that a leader bereft of a tertiary finish to his education was going to be regarded as irredeemably lightweight.

His humiliation in the party polls of 1993 when a tidal wave of support carried Anwar Ibrahim to the No. 2 position drove that point home starkly, if a mite cruelly.

Ghafar withdrew to lick his wounds.

It was left to the MCA to assuage things by reminding the public of Ghafar's worth when, every February when Ghafar's birthday came round, the BN's second biggest party's leadership cohort, past and present, would come round to celebrate the occasion with a birthday cake in Ghafar's honour.

It was an earnest of MCA's gratitude for Ghafar's mediation in the strife that pitted the faction of then acting MCA president Neo Yee Pan against vice-president Tan Koon Suan's one in the 1980s. Ghafar's ministrations had helped heal the breach.

The MCA's annual doffing of the hat to Ghafar was a nice touch in the sometimes cruel game of politics.

How would Ghafar feel?

Which brings us to the question of what Ghafar would have felt about the current situation in Umno.

Sure, he did not do anything when the Tunku addressed a poignant 'Dear Ghafar' letter to the then deputy prime minister in the late 1980s, imploring him to intercede in the matter of Lord President Salleh Abbas' impeachment.

Perhaps that was a matter that would have required a cerebral take on the issues arising, which perhaps would have been beyond Ghafar's ability; the present situation, however, would have occasioned something visceral in the man.

One thinks Ghafar would have been loath to accept the current situation in Umno.

Which makes the nomination of his grandson to contest Najib in a battle for the salvation of the nation a thing of pith and moment.

TERENCE NETTO has been a journalist for more than four decades. A sobering discovery has been that those who protest the loudest tend to replicate the faults they revile in others. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.