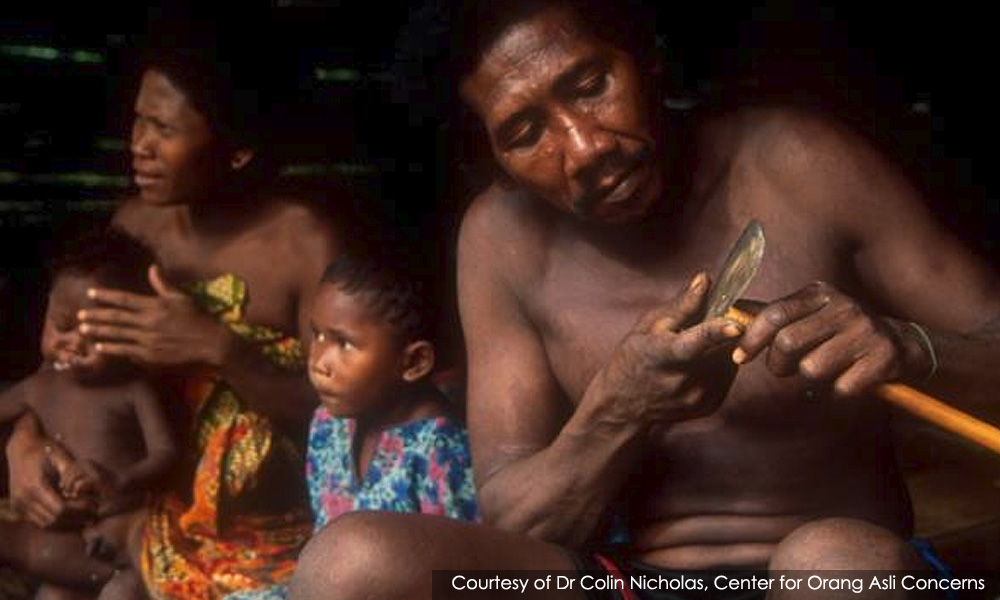

We have many examples of racism in Malaysia. But could one of them be against the most 'bumi' of the bumiputera?

The word 'bumiputera' comes from Sanskrit, and means 'sons of the soil.'

Yet ironically, discrimination could be facing the Orang Asli, a Malay term translated as the “original people” of this land.

At a forum in Petaling Jaya recently, five of the panel speakers lamented that there has been discrimination against the Orang Asli, and this had contributed to the recent tragedy where 15 Bateq tribespeople died in Kuala Koh.

The panellists included two academics, a doctor, a lawyer-activist and the director-general of the government department for Orang Asli "development" (Jakoa).

Ivan Tacey, an anthropologist from the University of Exeter who has studied the Bateq tribe for over a decade, described how the community was largely healthy circa 2008, with lush forests all around them.

But by 2014, the forests had been completely logged, the temperature had increased, while soil erosion affected river water supply.

"The forest was cooler, healthier, whereas life in the government resettlement village (of Kuala Koh) was harder.

"After being pushed off their (original) land, iron mining began (nearby)," Tacey told the What Led To Kuala Koh Catastrophe forum on June 28.

The forum was held in a bungalow in Petaling Jaya surrounded by trees, which houses the Centre for Malaysian Indigenous Studies (CMIS), part of Universiti Malaya.

Tacey explained that the Bateq were scared of going to government health clinics in town because some of them had encountered racism.

"They were worried about leaving their children there (at the clinics)," he said, adding that doctors did not regularly visit Kuala Koh itself.

Tacey recalled a sad experience when several members of another Orang Asli group, the Jahai, were sick.

"The doctors treating them used racist language (on the Jahai).

"An Italian anthropologist who was with us intervened, saying this was not right. Only then did the doctors' attitude change," he said, adding that there have also been some very good doctors who have treated the Orang Asli with respect.

Tacey pointed out that the Bateq village of Kuala Koh was not in some remote, inaccessible place, but was just less than 1km from one of the entrances to Taman Negara.

He said that while nearby Felda schemes had access to health clinics, schools and electricity, it seemed ironic that Kuala Koh was deprived of such facilities.

"The Bateq people have lived in the forests of Terengganu, Kelantan and Pahang longer than any humans, indeed before these three states even existed.

"They have their own sewang (communal feast and ritual singing ceremony) and religion, which is most peaceful and egalitarian. Their souls don't need to be 'saved' by others."

Official narrative

Adding to the anthropological view was that of a medical professional. This came from another panellist, Dr Stephen Chow, the leader of the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners’ Associations Malaysia (FPMPAM) medical outreach programme, which has provided healthcare to the Orang Asli since 2010.

Chow visited Kuala Koh on April 28, just a week before the crisis became national news, with a team of doctors and nurses, after being told of a ‘mysterious skin disease’ affecting people there.

"Actually, there was a small 'klinik kesihatan' (health clinic) building in the village, but it looked forlorn.

"There were cobwebs. It looked like it had not been used for a long time. There was no water to mop or clean the place."

Still, the team managed to set up a medical camp and examined 140 patients.

They found many cases of worm infestation, bacterial and fungal skin infections, lung infections (URTI) and cough, diarrhoea and malnutrition.

"But we did not find any cases of measles. We can diagnose measles. Any doctor who can't should go back to medical school."

This seems to contradict what Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad (photo) said on June 17, that the cause of the deaths among the Bateq was measles.

Another issue is the pollution of water supplies.

On June 14, Deputy Prime Minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail announced that tests showed that water samples were not contaminated with manganese from a mine about 3km from Kuala Koh, nor were there pesticides or herbicides in the water flowing off neighbouring oil palm plantations.

Chow then showed a copy of a press report, with the headline that the area was "mostly free from pollution," even though a water expert, Dr Zaki Zaninudin, agreed that the levels of iron and manganese "exceeded" Health Ministry safety levels.

"How high are the levels?" asked Chow. "You won't give this water to your son."

"Yet the deputy prime minister says the water is up to national standards (for raw drinking water)."

Chow said that preliminary analysis of three water sources around Kuala Koh in June showed that it was graded "Class 3" and not suitable for use as drinking water without extensive treatment, adding that his team will soon be releasing their own water test results.

His suspicions were further raised because his team found two patients with neurological symptoms.

One had slurred speech, and was confined to bed, while another could not walk properly.

"These could be signs of manganese poisoning, which affect the brain," he said.

"Further postmortems are needed, as an analysis of bone marrow can show if there was manganese poisoning."

Chow said, "The (official) narrative doesn't seem to fit (the reality)."

'Them' vs 'us'

While these kinds of forums are normally the preserve of academics and activists, it was a welcome surprise that Juli Edo (photo), the director-general of Jakoa, showed up to speak.

Juli, who is an Orang Asli himself, recalled, "When I visited Kuala Koh, there was clearly a divide, a 'them and us' situation.

"The relationship between us, the government service providers, and the Orang Asli was 'tak mesra' (not warm)."

Juli admitted that "the majority" of Jakoa staff were "not passionate" about their work, and were there just to "makan gaji" (earn a salary). He also lamented the "ethnocentric attitude" of the staff.

"The thinking is, we are of a high culture, and they (the Orang Asli) are of a low culture. Yes, I try to provide services to them, but they are dirty."

To make matters worse, Juli said the Health Ministry and Jakoa were "tolak menolak" (pushing around) the responsibility for healthcare onto the "other" side.

"Jakoa is a low-priority government department. We asked for RM23 million to take care of 45,000 Orang Asli students, but we only got an RM90,000 allocation.

"As for houses, we only got 150. I don't know how to distribute these among over 800 villages.

"So please, don't just 'hantam hantam' (attack) me. Ask the government too.

"We don't want to fight the government, but we only want to correct what is wrong. I ask our friends in the government, private sector and NGOs, please don't just criticise, give me two alternatives for every problem."

He said that the new government had given space for him to "cakap celupar" (talk frankly, even if it causes offence).

"So, I will speak up," he said, adding that he has stopped reading his WhatsApp just six weeks into his job because there are too many messages slamming his department.

"As for myself, I have retired (but was recalled). I can resign."

It was sad that the Jakoa director-general admitted there was discrimination and "ethnocentric" (the fancy word for racist) attitudes towards the Orang Asli.

No respect

Lawyer-activist Siti Kasim (photo) agreed that the Orang Asli were often treated without respect.

"I remember a case when an Orang Asli was suspected of having tuberculosis. He was put into isolation, in a back room with bird shit."

She said these kinds of attitudes made the community reluctant to go to hospitals.

She also lamented that leaders like PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang had once said, "How long more will the Orang Asli 'merayau' (be nomadic)?"

"That is wrong. The Orang Asli should be free to choose what life they want," Siti said.

However, she welcomed the fact that since Juli became Jakoa chief, he had made many positive statements.

"Before this, Jakoa was not on the side of the Orang Asli, but on the side of the government, especially to Islamicise them," adding that she may be taking on a case where the Bateq of Merapoh allege that they had been converted without full, informed consent.

Root cause of crisis

Colin Nicholas (photo), the executive director of the Centre for Orang Asli Concerns (COAC), highlighted that the root cause of the crisis was because the community's rights to their traditional jungle lands were not recognised.

Nicholas said that when he visited Kuala Koh ten years ago, the Bateq people were healthy, they had their forests and the river water was clean.

"They were in control of their lives and happy. They would play their guitars and sing."

"But between 2011 to 2012, the forests were stripped away by the Kelantan state government, first by logging, and then for oil palm plantations and mines.

"Without access to their traditional jungle resources, the Orang Asli have become malnourished."

Instead of forest fruits, some have ended up eating junk or high-sugar foods, leading to lower resistance to diseases, so much so that lung infections or diarrhoea can become fatal.

While there is talk of "relocating" the Bateq people from "unhealthy" Kuala Koh, Colin noted that this ignored the fact that they had already been resettled!

"In 2012, the Bateq were asked to leave the forests, and PPRT houses (for the poorest peoples) were built for them here."

If they are to be relocated (again), Nicholas suggested that they are allowed to return to a forest environment across the Pertang river inside Taman Negara.

"What is most important is that we must ask them if they want relocation and where. Everybody has the right to be who he or she wants to be."

Another issue was that the Health Minister had blamed the "nomadic" lifestyle of the Bateq for the lack of measles vaccinations. But Nicholas pointed out that Kuala Koh is a semi-permanent settlement.

"The Bateq are not fully nomadic. People take turns to go into the forests, others stay in Kuala Koh, which is like a base camp where they can meet outside traders."

Colin warned that Kuala Koh was not the only case where Orang Asli health is vulnerable after losing their forests.

"There are other areas along the Perak-Kelantan border, and even in (former prime minister) Najib Abdul Razak's area of Pekan," he said. "There are many ticking time bombs."

Given all that the speakers had said in this forum, one could be forgiven for concluding that there is discrimination, marginalisation and – dare we say it – racism, against the Orang Asli.

One year after the elections, while the politicians are busy grappling with racial-religious politics, a resurrected and shameless 'bossku', alleged gay sex videos and shadowy power plays, the most bumi of the bumiputera may still be wondering if their lives will be better in Malaysia Baru.

ANDREW SIA is a veteran journalist. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.