The old adage ‘Where there is smoke, there is fire’ is apt. Over the last few months, rumours of backroom deals to restructure the composition of the government have intensified to the extent that they have been publicly addressed by political leaders.

Discussion centres on a potential ‘backdoor’ government – a government not directly chosen by the people, but instead the product of elite negotiations for power. To understand the risks of these manoeuvres, it is necessary to step back and look at the drivers of this deal-making and the potential impact these have on Malaysian politics.

I argue any betrayal of the GE14 mandate will leave a lasting imprint, one which will deepen political polarisation and foster instability. Despite the cavalier attitude of leaders to engaging in such deals, ‘new’ Malaysians will not forget easily.

Money still the key driver

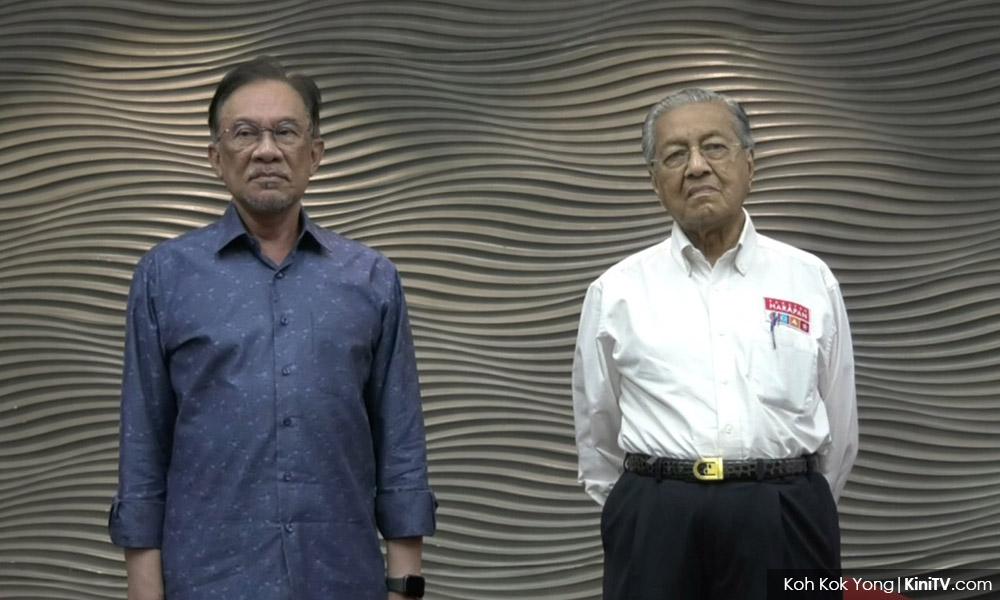

At its core, Malaysia’s ‘backdoor’ dealing revolves around the Dr Mahathir Mohamad-Anwar Ibrahim axis, support for different leaders, and is tied to different views of the political transition. It builds on the distrust that has plagued Pakatan Harapan since its conception, and which has continued to fester.

At issue is not only a power leadership contest, but access to patronage and resources. Money is still a driver in Malaysian elite politics, as oligarchic (and vested bureaucratic) interests remain strong. The elite want to be on the winning side, to secure their positions and access to contracts and coffers. In feudal fashion, some members of the elite believe their followers will accept their manoeuvring as long as they are in power.

Traditionally, coalitions elsewhere break apart due to policy differences. Disproportionally, what has distinguished pressures within Harapan has been primarily personality and personal interest, not policy. This said, two underlying issue areas have exacerbated tensions – different views on race/religion and, to a lesser extent, perceptions of political and economic reform.

A ‘backdoor’ government comprised of a Malay supermajority is being justified on racial grounds. Calls for ‘unity’ and ‘dignity’ are being galvanised by the elite to serve these interests – staying, returning or getting into federal power. This is premised on the racialised view of representation that Malays should comprise the overwhelming majority of positions. Hierarchical notions of citizenship and exclusionary views of nationhood underlie this approach.

Unlike the now-defunct Barisan Nasional (BN) where there was the (original) idea of power-sharing, a unity government is seen to marginalise non-Malays (essentially what has happened to the BN before it was voted out of office or even earlier). All sides are buying into the notion of Malay dominance and trying to win over Malay support, but vary over the extent they will marginalise non-Malays. The layering of religion over race has deepened the exclusionary trend.

The second difference is about reform, reflecting disparate world views. Harapan is comprised of both conservative and liberal parties, ideological differences which have contributed to the reversals, resistance and inconsistencies in bringing about structural political reforms and in the economy. Some in Harapan see the problems the country is facing narrowly as the product of Najib Abdul Razak’s leadership rather than being more systemic and broadly.

Thus, there are differences over how willing different mebers of the elite are to cooperate with those outside Harapan. In the ‘backdoor’ dealing, principles about reform are taking a back seat as there is open engagement with former BN component parties and the Islamist party PAS.

Public politicking

The process of ‘backdoor’ dealing has been quite open – both the underlying conflicts and alliance making. There has been a litany of attacks on individuals/parties, from alleged sex tapes to direct and indirect criticism of parties and leaders. These have escalated in frequency, and denials have lost credibility in the sea of non-stop politicking.

Malaysia’s political system allows for considerable political fluidity. There are no penalties for changing party loyalties (frogs). Since GE14, 20 MPs have changed their political affiliations (with two of these becoming independent and one changing the name of their party (from United People's Party, UPP, to United Sarawak Party, PSB, in 2019) and 17 joining different parties in Harapan.

There have been two main waves of defections – initially after GE14 and subsequently surrounding changes within Umno, notably the party leadership contest. In recent months, a few of those who were in independent limbo have been allowed to join parties, as part of the intensification of ‘backdoor’ jockeying.

Loyalty changes have also happened within parties – support moving from PKR deputy president Azmin Ali to party president Anwar, for example, and within Umno, as the party is deeply divided and split into two major camps. More recently, there have been ‘loyalty’ declarations, and, importantly, the formation of new alliances, such as the Umno-PAS Unity Charter.

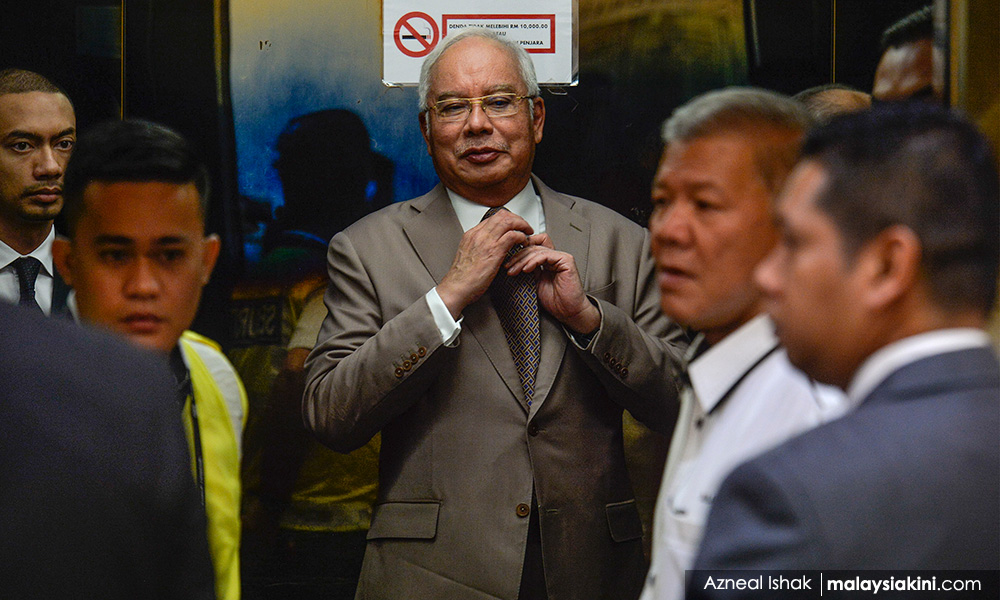

The latest of these is the supposed ‘third force’ by Umno president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Malaysia’s most criminally charged politician. These public events have been complemented by alleged private meetings seeking support. Increasingly, who the new members (and what they may have done) are less important than their loyalty pledge in the elite contestation.

A fluid numbers game

The assessments of loyalty vary sharply, as both sides are claiming an ‘upper’ hand. The fact is that both Mahathir and Anwar have a significant core group of support in any reconfigured government scenario, with Mahathir perceived as having the advantage in numbers over Anwar.

There are different powerbrokers, with the most important of these being the Umno camps, PAS, GPS, and Warisan. Each of these ‘kingmaker’ groups will expect deliverables, with those ranging from removing criminal charges to greater autonomy and resources. The impact of having PAS in any new government will be a greater accommodation to a more conservative religious agenda.

A key issue would be the choices of Sabah and Sarawak parties, whose numbers are crucial for any federal government, and whether they will be willing to partner with PAS. This issue is a pressing one for GPS, who will have to face the electorate before the end of 2021. Those who change loyalties will have to justify this to the electorate, a difficult task if the process is seen to be driven by personal interests and whose new allies can alienate their own political base.

There is a considerable number of ‘soft’ supporters and undecided who are being wooed and pressured by different sides, arguably at least 15 percent of the parliament. Party loyalty is being tested, even within parties, with voter loyalty increasingly getting short shrift. Every seat will count and the situation is one of high stakes and fluidity.

Democratic betrayal

The consequences of a ‘backdoor’ government will be serious. It is not just about who gets power. At issue is a contraction of democracy and further destabilisation – both of which will transform Malaysian politics.

Malaysia is unique in that it is one of the few countries in the world where coalitions are formed before it goes to the election. Importantly, voters vote for the coalition – the collective of its leadership and parties. It was the combination of all the parties that allowed the first change of federal government in Malaysia’s history.

Despite the prominence of Mahathir’s leadership, the GE14 mandate was for Harapan in its totality, not the individual leader(s). Mahathir and his party Bersatu would not have won power on its own. This is also the case for Anwar and PKR. And for the other parties as well – DAP, Amanah and Warisan (which stood on its own and whose numbers allowed Harapan a larger majority). A significant reconfiguring of the governing coalition will violate the GE14 democratic mandate.

Parties form and re-form alliances. Malaysian history is riddled with examples, notably after the 1969 racial riots and in the changing alliances in the opposition, including in the evolution of Harapan itself. There are bound to be changes in coalitions, as this is the nature of coalition governments. A radical ‘backdoor’ configuring of a coalition government in office, however, would be a new threshold for Malaysia. It would reflect a hubris and disregard for voters among the political elite that would be unprecedented.

The impact would be potential destabilisation. Any ‘backdoor’ government would have to figure out how to work together, and arguably have similar cooperation problems that have plagued Harapan, without a public mandate. Without elections, it will be seen as illegitimate by a large share of society. The issues of future leadership in any new arrangement will also remain unresolved, and this will deter investment in Malaysia and contribute to further power jockeying. At 94, Mahathir cannot govern in perpetuity and Malaysia has to face the issue of who will succeed him.

A potentially new racialised and exclusive composition of a ‘backdoor’ government will also affect markets and capital flows. A Malay nationalist ‘unity’ government could negatively affect Malaysia’s global reputation and economy, a fact that is underappreciated in the increased racialised rhetoric in recent months. The prospect of capital flight and reduction of investment is real. One needs only to look at the impact of the coup in Thailand in 2014 to see the negative effects of contracting democratic space.

The most potentially destabilisation impact will be further polarisation of society along ethnic lines. This trend in recent months has escalated emotive ethnic tensions in society, and if tested further, will increase the risks in Malaysia itself. The impact of persistent attacks along ethnic lines and the rise of demonising hate speech across racial groups has ratcheted up emotions. There will be spillovers to Sabah and Sarawak as well, with greater calls for autonomy as many in these states reject the peninsula-based race-based formula of politics.

Anger and uncertainty

The risks extend beyond those noted above – the violation of a democratic mandate, minority and regional exclusion, reputational implications, economic contraction and destabilisation – they also have the potential to evoke strong reactions in society.

Malaysians remain angry with abuses of power and frustrated with government responses to address persistent problems. This anger has not gone away. In fact, a ‘backdoor’ government formed behind closed doors has the potential to get Malaysians out their front door to mobilise. Any betrayal of trust could seriously delegitimise leaders and parties. Malaysians are not likely to forget or ignore this sort of double-dealing. One does not need to look far to see how protests are reshaping politics in Asia.

The recent student protests in Indonesia reflect deep resentment with oligarchic manoeuvring.

Minimally, a ‘backdoor’ government will increase cynicism, as trust in leaders and faith in the electoral process will be damaged. In the longer term, a process of delegitimation of parties will deepen, increasing the demand for new political forces to emerge. Keep in mind, Thailand’s opposition Future Forward emerged as a new political force in less than three months.

To date, the ‘backdoor’ government option has increased political uncertainty and undercut Harapan. For the opposition, this is the only viable immediate path they have to national power, but it is also a vehicle to undermine the legitimacy of Harapan and distract it from governing.

From the onset, the opposition has worked toward dividing Harapan. Some in Harapan are opting to exacerbate these divisions. Herein lies a key problem, the destructive politicking. This is undercutting Malaysia as a whole. The ‘backdoor’ process will strike a blow to the nation’s democracy with transformative potential spillover effects.

If Harapan is to move forward, it needs to move away from such ‘backdoors’ and put its house in order. It needs to reduce risks and work for the country as a whole – to put Malaysia, rather than elite interests, first.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.