We will be starting the new year with our hopes for a New Malaysia dashed by the announcement of Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mahathir that the bumiputera agenda (expiry date 1990) will continue.

As in 1971, when the New Economic Policy started, and again in 1990 when the New Economic Policy was replaced by the National Development Policy – which then morphed into the New Economic Model in 2010 – we are treated to the same ludicrous doublespeak.

Coined by George Orwell in 1984, doublespeak has been defined by some as “the ability to accept two conflicting beliefs, opinions, or facts as valid and correct, simultaneously… which may happen because of someone being willfully perverse or as a result of faulty logic.”

Consider this. In the process of announcing the continuation of this ‘Never-ending Policy’, the prime minister tells Malays to stand without the ‘tongkat’ (crutch) that the government is going to continue to provide them.

Even more doublespeak was heard with Bersatu president Muhyiddin Yassin’s pious wishthat the implementation of the new bumiputera agenda “must contribute towards economic growth with benefits enjoyed by all Malaysians.”

Why is it not possible to have an Affirmative Action Policy for the B40?

I find it remarkable that after more than 60 years of affirmative action for the bumiputera, we still cannot find intellectuals who can devise a race-free affirmative action policy.

Our scholars and intellectuals have been schooled in the best universities overseas, but still cannot come up with a policy that does not discriminate on the basis of race.

An exception is economist Mohamed Ariff, who spoke out against such racially discriminatory policies in 2013:

“The NEP had outlived its usefulness and the government must move affirmative action policies from race-based to needs-based. This policy shift will ultimately benefit the Malays as they form the bulk of 40 percent of households in the lower-income bracket.

“The government’s policies seem to be populist in nature and not focused… handouts should only be given in crises, such as famine, as they remove the incentive to work hard. The Malays would not be able to compete in a globalised environment if they continued to depend on handouts.”

Economist Edmund Terence Gomez has often questioned the race-based criteria for wealth distribution:

“Why the continuing fixation with numbers when many Malaysians, among them even members of BN component parties, have questioned the veracity of these government-released ownership figures?

“Even if bumiputera equity ownership is increased to 30 percent, would this mean that wealth has been more equitably distributed among members of this community or between them and other Malaysians?

“And, most importantly, should we continue to perpetuate a discourse on equitable wealth distribution among Malaysians along racial lines?”

At the Bersatu general assembly, the prime minister justified the continuation of this racially discriminatory policy on the grounds that more than 70 percent of the B40 are bumiputera.

If that is so, why not have an affirmative action policy for the B40, which would be race-free and would be agreeable with obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Icerd).

Why practise racial discrimination and be noted as one of the few outcast nations that has not ratified Icerd?

What happened to the slogans for ‘New Malaysia’, ‘Asian Renaissance’, ‘Malaysian Malaysia’? Have these all been empty slogans?

The other leaders of Harapan – Anwar Ibrahim, Lim Kit Siang, Mohamad Sabu, P Waythmoorthy, who have condemned racial discrimination in the past – have not said a word about the continuation of the bumiputera agenda announced by the prime minister. Does silence signify consent or indifference?

Litany of crony capitalists

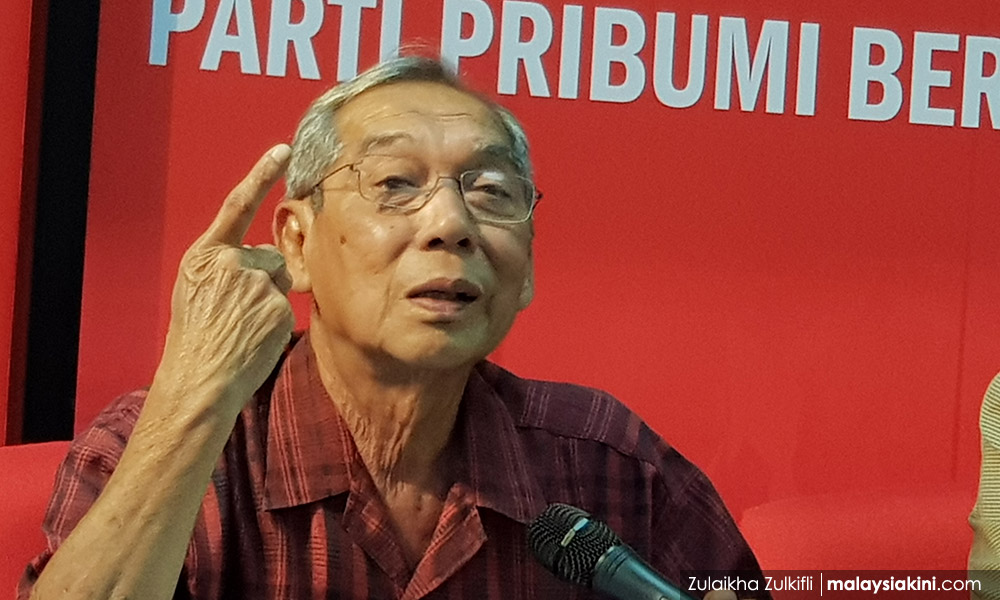

Given the Pakatan Harapan manifesto, it was shocking, though sadly not surprising, to hear Bersatu vice-president Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman (photo) supporting delegates at its general assembly by calling for government resources to help the party.

The former Election Commission chief said Bersatu must do all it could to win elections “by hook or by crook.” He said, “Looking at the situation now, we cannot defend our position as the governing party because the division chiefs are being left out of contracts.” Right, so contracts for the boys!

And was it surprising that throughout the years of the bumiputera agenda, Malaysia has featured high on The Economist‘s crony capitalism index.

Uncontrolled rent-seeking has allowed politically well-connected billionaires to double their wealth, thereby posing a threat to the free market, The Economist said. These rent-seeking industries include those easily monopolised, and that involve licensing or heavy state involvement, which it said was “prone to graft”.

This skewed bumiputera agenda is at the heart of the kleptocracy problem the Harapan government claims it wants to fix after the 14th general election.

From the 1980s on, Mahathir’s privatisation of state assets ensured the divestment of state capital into the hands of favoured Malay crony capitalists.

The success of the NEP in restructuring capital has, in the process, increased class differentiation within the Malay community. Thus, instead of targeting and providing strategic aid to the poor of all ethnic communities, the Umno ruling elite has continued to use the tried and trusted strategies of race-based cash aid and uplift plans aimed at bumiputera.

Authoritarian populism of the Malaysian state

The truth is, as Anne Munro-Kua has analysed in her book, the Malay ruling elite in Malaysia has relied on an authoritarian populist style of rule to stem the possibility of the peoples from different ethnic communities uniting into a class-based political force, and to simultaneously ensure the continued political domination of the Malay-led coalition.

A communal populist approach continues to be used to deflect the economic grievances of the Malay labouring classes against capitalist exploitation into a race-based ideological allegiance to the Malay ruling elite.

The GE14 results will further ensure Harapan rely on such populist policies to try to capture the Malay rural votes.

While bumiputera policies are intended to benefit all bumiputera, the reality is that these policies have been usurped by the privileged Malay elite, whose weak enterprise culture and expertise has had damaging consequences for the economic health of the nation.

The bureaucracy has grown in tandem with the populist measures by the state capitalist class to carve out bigger and bigger slices of the rural and urban economic pie.

Institutional obstacles to attaining high-income status

According to an IMF working paper, Malaysia, as compared to other Asian countries, faces a larger risk of slowdown stemming from institutional and macroeconomic factors.

A recent Asia Foundation Report also points to a compelling need for Malaysia to shift from a race-based to a needs-based policy in order to address imbalances in society, and improve the democratic process to ensure good governance and that the rule of law prevails.

It points out that poor institutions could deter innovation, hamper the efficiency of resource allocation and reduce the returns to entrepreneurship.

The report goes on to reason that despite the numerous bold policy measures and long-term plans introduced by the government over the years, Malaysia’s economic progress continues to be plagued by a lack of innovation and skills, a low level of investments in technology, declining standards in education, relatively high labour cost and sluggish growth in productivity.

These lagging factors can be traced to the continuation of a backward racial discriminatory policy.

Thus far, Malaysia’s education system has failed to produce the skills and talent required to take the country’s economy to the next level. A key obstacle lies in the government’s failure to promote a fair and open economy.

The bumiputera policy and insufficient checks and balances continue to hamper the country’s economy, leading to poor practices in governance. Reforms, especially the replacement of racial discriminatory policies with race-free inclusive policies, are critically needed to rally the nation to achieve its economic objectives.

Affirmative action based on need, not race

In Malaysia, since the passing of the deadline for the NEP in 1990, it makes developmental sense to implement a new socially just affirmative action policy based on need or class or sector.

Thus, if Malays are predominantly in the rural agricultural sector, the poor Malay farmers would be eligible to benefit from such a needs-based policy while the rich Malay land-owning class would not. Only such a race-free policy can convince the people that the government is socially just, fair and democratic.

The cost and consequences of the racially discriminatory policy in Malaysia have been immense especially since the NEP in 1971. It has caused a crippling polarisation of Malaysian society and a costly brain drain.

While the Chinese middle and working classes in Malaysia have largely adapted to this public sector discrimination by finding ways to make a living in the private sector, this has not been so easy for working class Indians.

Many Indian Malaysians have found themselves marginalised, much like the African Americans in the US were, especially after the destruction of the traditional plantation economy.

The cost of preferential treatment has also seen greater intra-community inequality, with higher class members creaming off the benefits and opportunities.

More potentially dangerous and insidious is the effect this widespread racial discrimination has had on ethnic relations in this country. Unity can only be promoted through an affirmative action policy based on need, sector or class – but never on race.

KUA KIA SOONG

– M’kini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.