It was 1963 and I was a mere six-year-old. There I was, with three of my siblings, having the run of the place outside our estate bungalow in Gomali Estate, near Segamat.

We were playing 'police and thief' with our Hindu neighbours' children, when an itinerant holy man or sadhu, clad in a saffron dhoti, meekly strolled into our game.

He had a silver tray with him, which hosted the figurine of a Hindu deity, some holy ash (vibuthi or thinoor in Tamil) and fresh petals of jasmine.

The Hindu children ran to him as if he was Santa Claus, but my three siblings and I watched as he blessed our playmates with vibuthi on their foreheads.

As the sadhu looked in our direction invitingly, our friends urged us to receive the ash, but we were reluctant until someone cajoled, “Receive the ash. Ghosts will not disturb you if you have it on your forehead.”

That was all we needed (the ghost part) to be encouraged to receive the sadhu’s ash, much to his delight. As he turned to go, we dashed into our courtyard for a drink of water.

The rebuke

Lo and behold, there she was, my eldest sister, Anne, who was our chief guardian then. Seeing the ash on our foreheads, she went ballistic.

“Who told you all to put that ash on your forehead? See how you have defiled yourselves,” she screamed. “We are Christians and more so, Catholic!” she continued.

“Go and wash yourselves, kneel down at the altar and beg God for forgiveness,” she said, in the typical tone of a Mother Superior. Without relenting and in equally stinging tenor, Anne rebuked: “Confess this sin to the priest on Sunday, you pagans.”

Not knowing what sin we had committed, we briskly brushed off the ash from our foreheads and hurriedly retreated to the bathroom to cleanse ourselves of this so-called cardinal sin.

Even our little Hindu friends quickly obliterated the ash from their foreheads and bolted for dear life.

We surrendered to the corporal punishment before the altar with rosary in hand.

I was confused and hurt, and pondered my first 'knowledge' of the differences between religions – that Hindus and Christians, and all the more Catholics, are children of different Gods.

That they can play together, that they can share a meal at each other’s table, but when it comes to keeping the hantu away, different gods have different weapons. The Hindu God has vibuthi and the God of the Christians has holy water.

What a rude awakening it was for a tender six-year-old to unwittingly come to grips with early lessons on “comparative religion.”

When my dad arrived home from work, he was surprised to see us kneeling at the altar. Before he could say anything, Anne stepped forward and presented her case, stating the reason for the punishment.

Being the staunch and stern Catholic that father was, we were terrified and braced for the grandest beating of our lives, but dad surprised us this time.

He gestured for us to get up from our kneeling position and said to no one in particular: “They are too young to understand these things… perhaps, they will, when they grow older.”

Case dismissed! What a joyful reprieve it was for us little beings, embroiled in this “clash of religions” so early in our lives.

Today, when we meet, and when this vibuthi incident is mentioned, we laugh at ourselves over this caper, along with big sister Anne who is now 78.

New narratives from Rome

Ironically, while this vibuthi flashpoint got us siblings in trouble, over in Rome an assembly of bishops was in session, having commenced in 1962.

This meeting (or Vatican Council II) was called by Pope John XXIII and the reason he summoned the world’s bishops to his citadel were, in his own words: “To discuss ways on how to let some ‘fresh air’ into the Church.”

By “fresh air,” the late pontiff had discerned that certain aspects of Church life needed a “makeover.” He believed that it would be in good order for the Church to resonate with the changing landscape of the modern world, and for it to live the new signs of the times in an air of rejuvenated sanctity.

At the conclusion of the Council in 1965, 16 decrees, declarations, constitutions and doctrines were proposed and accepted.

Among them was one titled “Declaration on the Relationship of the Church with Non-Christian Religions (Nostra Aetate),” which I found relevant for us Catholics living in a multiracial and multi-religious landscape.

The declaration read (paraphrased): "The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in non-Christian religions, and emphasised that any discrimination based on race, colour, religion or condition of life is foreign to the mind of Christ."

Profoundly, one of the most noticeable changes that came with Nostra Aetate was the disappearance of the unpalatable term “pagan” from the lips of Catholics. The derogatory term was replaced with the more charitable collective term, “people of other faiths.”

Religiosity’s inviolable harmony

Growing up and living in Malaysia offers every citizen the perfect social, as well as psycho-spiritual, template to appreciate Asia’s multifaceted religiosity in all its inviolable beauty.

I recall the time, when I lived with a Hindu family in the Section 5 area of Petaling Jaya, where a daily rendition of mixed liturgical chorales, whether sung, chanted carolled, intoned or recited, came as blissful music to my ears.

The muezzin’s daily cantor of the azan, rolling out liltingly from the nearby Section 3 mosque is the first euphonious lyrics to sanctify my day. “Allah-Hu-Akbar! Allah-hu-Akbar! Ash-hadu-an la ilaha illa Allah. Wa ash-hadu-anna Muhammad-ar-rasulullah. Haiya alas-salaah. Haiya alal-falaah. Allahhu-akbar. Allah-hu-akbar. La ilaha illa Allah.”

I am stilled into silence each time I listen to the azan, solemnly intoned in slow measured cadence, then rising to a crescendo and slowly fading off into a sullen pitch of tranquil calmness.

But the abrupt silence ceases, as the birds of Gasing Hill chirpily sing their morning lauds, while I recite Psalm 95: “Let us come before Him with thanksgiving and exalt Him with music and song.”

Psalm 95, is a praise song that extolls God as being great and the King of His people. It reads so closely to the proclamation in the azan, Allahu Akbar (God is great), a decree that will be affirmed four more times in the day by the muezzin.

No sooner as I conclude my morning devotion, the radio from this Hindu household rolls out the Gayatri mantra – a sacred chant that demonstrates the unity that underlies manifoldness in creation.

The hymn attests that it is through recognition of this unity that humankind could fathom the multiplicity and plurality of things and beings.

Then, as if on cue, the pealing of church bells could be heard, tolling with the chiming decibels raised by the monks. The Catholic faithful have gathered at the nearby St Francis Xavier’s Church for Saturday’s sunset Novena, the organ striking the first high notes of the quaint 'Ave Maria'.

Not to be outdone, the myriad canticles of the world’s pieties continue to ring out at the Sri Sithi Vinayagar Temple on Jalan Selangor as the sun slowly drops beyond Petaling Jaya’s skyscape. The temple’s gopuram captures the reflection of the fading celestial body in a sheen of multiple hues.

Here, Hindu devotees have convoked to celebrate a pooja – where the mellam (drum) and nadhiswaram (clarinet) fight for attention.

Bells, and more bells, ring out as the ritual comes to an end in a chorus of Om – accentuating a sublime salute to the dynamics of the day’s sanctities.

What divides Malaysians?

Various threads have kept the fabric of Malaysia from unravelling – from the struggle for independence to the constitution, from democracy to Harimau Malaya, and from murukku to P Ramlee movies.

That these modules add up to an equation that unites Malaysians is good reason for every citizen to rejoice and be glad.

However, every so often, this equation is confronted by an opposing matrix that threatens to sow the seeds of division. We have a history of hurts, which are almost and always caused by religious and racial agitation.

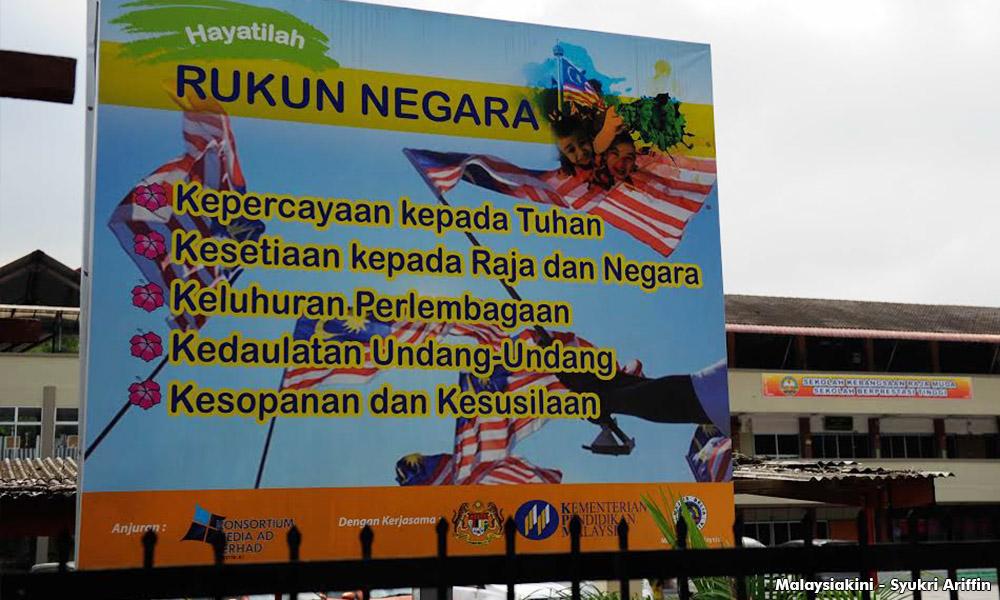

In response to the race riots, the Rukun Negara was put in place by the government as a way of fostering unity among the many races in the country.

Magnum opus or wall decoration?

It is 50 years today since the May 13 riots and 51 years since the first time the Rukun Negara was proclaimed on Merdeka Day in 1970, but has anything changed?

Today, as we citizens proclaim the Rukun Negara, do we sincerely berikrar (vow) to live by its principles, or do we just recite it mundanely as a set of beautifully written statutes – a magnum opus that serves better as wall decoration?

The Rukun Negara was and still is a noble idea. However, regrettably, it has failed to achieve one of its major objectives - to foster religious and racial harmony among the nation’s citizenry.

Its virtuous precepts encounter opposing crosswinds every so often, largely from political and sectarian narratives - rendering it meaningless and impotent.

Acts of intolerance

The infamous 2001 Kampung Medan incident, purportedly caused by a wedding, a funeral and a misunderstanding over a smashed car windscreen, caused clashes between the Malay and Indian communities living in the area. The incident took the lives of six people. and scores were injured.

Long before this incident, in the little village of Kerling in Selangor, statues of Hindu deities in a temple were smashed by Islamic zealots.

In the August 1978 incident four men were killed when they returned to smash more statues at the temple, but were confronted by Hindu men guarding the premise.

On August 28, 2009, a group of Muslim men protested the planned relocation by the Selangor government of a Hindu temple from Shah Alam’s Section 19 to a new location in Section 23, a Muslim majority enclave.

The protest, held in front of the Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah Building, was infamously dubbed the 'cow head protest' as the protestors brought along the head of a cow, an animal sacred to Hindus. They then proceeded to stomp on the animal’s head and spat on it before leaving the site.

More recently, on Nov 27 last year, clashes happened at the Seafield Sri Maha Mariamman Temple in USJ 25.

In this incident, devotees, who had gathered at the temple to protect it from impending demolition were reportedly accosted by an outside group, sparking scuffles. The incident unfortunately ended with the death of firefighter Muhammad Adib Mohd Kassim.

In 2010, several churches in the country were attacked with petrol bombs following a court decision on the usage of the term “Allah” by Christians in their worship and literature.

Apart from the churches, a surau in Klang was also hit in apparent retaliation, while a Sikh gurdwara in Sentul also took a hit. (Sikhs too use the term “Allah” in the Punjabi language during worship.)

These incidents and others such as the seizure of Bibles by the authorities, the threat to burn the Christian holy book by certain individuals, the desecration of the Catholic Holy Communion by two Muslim journalists from the Al Islam publication, and a string of attacks on Hindu temples in Penang in 2016, should never have happened if we had held on firmly to the precepts of the Rukun Negara.

The Rukun Negara, among others, pledges to achieve unity among Malaysians and to ensure a liberal approach towards the country’s rich and varied cultural traditions. So, where did we go wrong, what are the fault lines?

Perhaps these acts of intolerance boiled over from our hidden guile of sectarian sentiments – when push came to shove – triggered by narratives from certain people, pressure groups, institutions and politicians being perceived by the masses as unjust and unfavourable?

Ample space for all

I have shared some personal interfaith encounters in this story to highlight a point made by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa.

When he was heckled by a white supremacist and ordered to step off the pavement which was reserved for the white community only, Gandhi meekly responded: “There is ample space for all of us to walk along together on this pavement. Come, let us walk together.”

Ours is a nation of many races and people of many faiths. However, harmonious living does not come from thin air. It has to be engineered, taking into account ethnic differences and divergent expectations.

As a nation, we cannot afford to take goodwill and societal peace for granted even if the precepts of the Rukun Negara has ordained a recipe for the unity of races.

In order for us to walk together on the same pavement, each generation has to explore fresh ways to build bridges and deepen inter-religious understanding.

Certain unpalatable narratives such as the mere sighting of the holy cross – the universal symbol of Christianity – can weaken the akidah (faith) of Muslims in this country – or that the teaching of non-Islamic religions in schools may “impact negatively” on the Muslim populace should have no place in our plural society.

We can all appreciate the fact that each religious group may have fundamental core beliefs which may be different and opposed to the theologies of another religion.

But does that mean devotees of one religion cannot develop meaningful bonding across religious lines?

Evangelist Zakir Naik (photo) repeatedly prides himself as being a student of religions during his preaching rallies. He has enormous knowledge of the many religions of the world, and yet he remains a fervent Muslim with his akidah very much intact.

Though I think some of his take on non-Islamic faiths are theologically defective, I have gained voluminous knowledge and understanding of Islam through exposure to his preaching.

Having learnt so much about Islam from this preacher, I still remain Christianly Malaysian because my akidah too is strong and intact.

Every year during Ash Wednesday, I have ashes dabbed on my forehead by a Catholic priest to remind me of the fragility of life. Ash Wednesday, which translates in Tamil as Vibuthi Thiruvilla, also reminds me of the ashes placed on my forehead by the Hindu holy man in 1963.

It is fascinating that there are similarities in worship and 'ritual forms' among world religions. Perhaps, the transition that we have to effect is to 'celebrate' the similarities and 'respect' the differences.

In this way, we can find ample space for ourselves on the common pavement, and be able to embrace the world.

JOSEPH MASILAMANY is a veteran journalist. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.