When the Malaysian United Indigenous Party, or Bersatu, was set up in September 2016, both Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Muhyiddin Yassin were on the same side – both rejecting Umno and the kleptocracy of the Najib Razak government. Last week, after one leader instructed his ally to sack the other leader and another leader claimed he would sack the first leader, the escalating squabble inside the party showed the public the deep split that extends beyond the two men.

At issue are personal loyalties, principles (what little remains of them), pride and power – with the latter gluttony for power a driving force. Neither man is willing to step away from the fight or their desire for control of the top position, so far.

The person who has the most to lose is Muhyiddin, who kicked a parliament vote down the road, and is now facing his first real litmus test of power – whether he can command his own party. Rather than strengthen Muhyiddin’s leadership, events so far in the Bersatu battle have undermined him and are raising the question whether the damage inflicted will leave him and the party with nothing at all.

Multiple battlegrounds

On the surface, there are two main ongoing intertwined battles taking place – for control of the party and for control of the government.

The scripts involve similar storylines, but the endings are yet unfinished. The fight over the party involves using levers of power such as the Registrar of Societies (ironically using changes that Mahathir put in place in 1988), legal battles and persuasion (both personal and financial). With Bersatu’s election and formal Supreme Council meeting weeks away, the party battle is being played out in public - in office occupations and press conferences. This will garner public attention, with Mahathir gaining ground when he is both pushing back and being pushed out.

The fight for government – an even higher stake in the political war – is a perpetual numbers game. This is largely taking place behind closed doors. The Raya period has been one of intensive meetings. Rather than share a feast around a table, the discussion has centred on who will get what share and whose feet will be in the chair at the head of the table.

Many are eating at different tables and looking at what is on offer. The question is not just the numbers – but who exactly is at which table and with whom and, importantly, their stability and acceptance by others in the various groupings. As with the party contest, the fight for government is likely to continue into Malaysia’s long Raya season – with it increasingly overshadowing the party contest as it evolves ahead.

Behind these battles is a more long-term struggle taking place over who can claim hegemony of the Malay electorate – which party in fact represents the Malays. Already PAS and Umno are claiming this mantle, although both vie for the top spot even as they collaborate with their competitor. Umno has not given up its goal of reclaiming the title.

There is little appreciation that changes among Malays – their diversity, different generational outlooks and interests and the increasing party options provide many choices to Malay voters – make an outright ‘winner’ unviable. Despite clear Malay divisions, the battle to claim to speak for and ‘protect’ them continues.

All not for one

As these battles are being played out in public, it is useful to step back and look at how Bersatu became so divided and has now become the cauldron of Malaysia’s current political trajectory.

The party came together over one man – Najib Razak. To address the perceived greed and excesses of office associated with the 1MDB scandal and to respond to how Najib treated those who challenged him – including the sacking and filing of charges against critics. The willingness to work with Najib in Umno to apparently undercut the efforts to hold those associated with 1MDB accountable has deeply divided Bersatu as it runs counter to the rationale originally used to set up the party.

From the onset, Bersatu was a party full of other contradictions. It claimed to be about reform, but created itself in Umno’s image, along racial lines and later while in government with its endorsement of patronage practices. It served as a vehicle to bring in new (and old) claimants to the widening contest for access to the spoils of holding office.

While some Bersatu rejected these practices – calling for multicultural outreach and clean government practices – others, arguably the majority, held onto the view that holding power should be a means for aggrandising wealth and distributing this wealth to loyalists. Bersatu justified these practices as the ‘new Umno’ claiming these were for the Malay community – a claim that is not justified given its greed and weak distribution networks.

Bersatu was and is also divided in its personal loyalties. Both men – Mahathir and Muhyiddin – brought in their loyalists and used the party as a vehicle to (re)gain power. Of the two, Mahathir’s cache was always larger, in that his pull served to get the party its original numbers. He was the political heavyweight. Bersatu was synonymous with Mahathir’s return to power, a vehicle to allow this to happen.

Muhyiddin was in the front passenger seat, but he was not the driver of the party. This was also the case throughout Pakatan Harapan’s tenure in office. Now as developments try to change those at the driving wheel, the party itself is at risk of a crash.

Rebels without a cause

Mahathir apparently had grand ambitions for the party – believing the party could replace Umno. Bersatu was supposed to be the party to capture Malay support. He disproportionately gave Bersatu leaders higher numbers of cabinet seats and control of multiple state governments, despite its lower performance in terms of seats in GE14.

These ambitions to be a new mass-based party did not materialise. Bersatu’s efforts to build its party machinery never gained ground, as member numbers remain low. This was shaped in part by the fact that many Bersatu members themselves were more committed to securing their own position rather than building the party. Umno’s post GE14 revitalisation – albeit uneven and nowhere near its earlier years – also undercut Bersatu’s outreach. The competition for the Malay electorate is a crowded field, with PAS and other Harapan contenders as well.

One of the most important issues was that Mahathir-led Harapan was never a ‘Malay government’ despite efforts by Bersatu to project his image as a ‘protector’ of the Malays. In Mahathir 2.0 as Malaysia’s ‘saviour’, Mahathir never held this mantle due to the fact that Bersatu’s level of support among Malays (a quarter of the community in GE14) was always less than its Malay-based competitors – Umno and PAS.

Harapan’s policies, communication weaknesses and Bersatu’s minimalist outreach did not alter this status. In fact, Malay support steadily eroded as the more Bersatu and Harapan reached out to Malays, the more of its base left.

Mahathir also miscalculated in assuming that the Malays who in fact voted for Harapan were mainly interested in ‘Malay’ issues rather than overall economic performance and reform. The outdated lens to see Malays as all alike – a unified voting bloc with a similar vision – is blind to the varied realities and ideals among different generations of the community at large. Mahathir also mistakenly assumed the Malay support given to Harapan was for him, rather than for the broader cause of change or other leaders in Harapan, notably Anwar Ibrahim.

Muhyiddin is making the same mistake of misreading Malay support as unified as he touts the need for political stability and Malay protection but faces serious worries about how his government is (or is not) able to manage the economy and Covid-19 challenges. The focus of many is on deliverables and livelihoods across races.

Eroding electoral base

To address the inability to grow Bersatu through mass membership, Mahathir took another route. This was the route of accepting defectors. This has been a fatal mistake for Bersatu’s future and is playing a large role in the ongoing battle inside the party.

There are two groups in the party – the original 13 who were elected to parliament – all of which, including Mahathir and Muhyiddin, got into office riding on the idea of reform and accountability for 1MDB. All contested in three-corner contests that split the vote.

Only one leader won the most Malays in his constituency – Mahathir. Using polling station results of Langkawi, it is estimated Mahathir won 53% of Malay support. He secured the majority of non-Malay support in this seat, an estimated 92% Chinese, 53% of Indian, and 66% of Other voters.

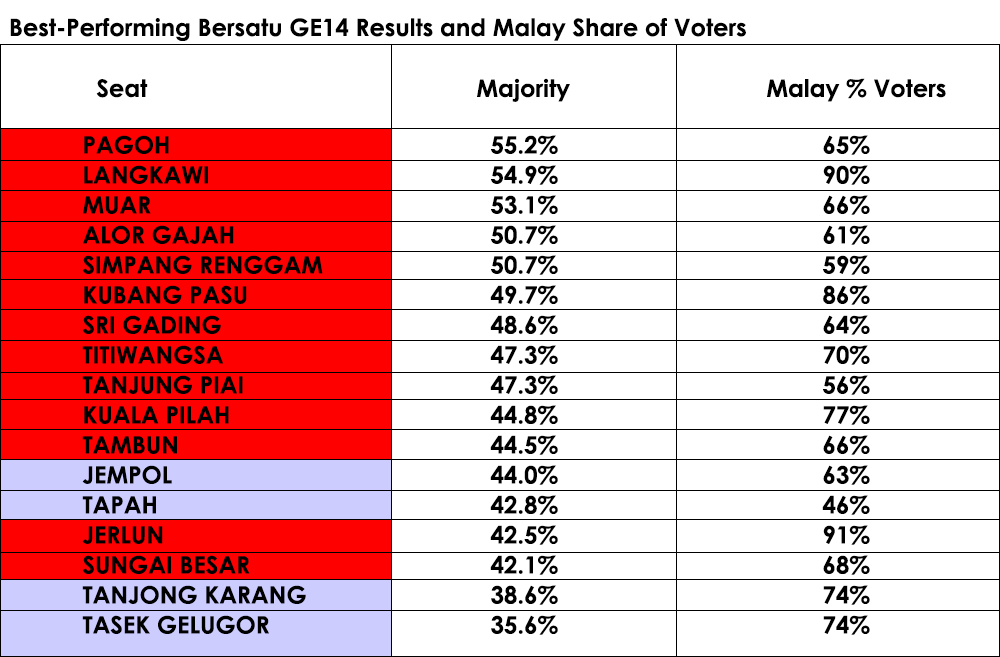

Only three won a clear majority of the overall vote – Muhyiddin (Pagoh), Mahathir (Langkawi) and Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman (Muar), but these were not large majorities. All the other seats won were by very slim majorities of pluralities, winning the most votes in three-cornered contests. The chart below shows the best-performing seats for the party in GE14 and the share of the Malay electorate in these seats.

To keep these electoral results in mind, the level of support for Bersatu nationally was small – 6% of the popular vote – and shaped by the context. Bersatu does not have a base of voters to rely on. More often than not in GE14, they were spoilers affecting the fortune of Umno and PAS rather than victors.

The party’s decisive support came from multi-ethnic support, especially in Johor and even in Kedah, among younger voters and in some seats lower-class voters. As the post-GE14 by-elections show, especially Tanjung Piai last November, they have lost ground among these voters.

It is important that among those openly loyal to Mahathir in the Bersatu party contest are among the original 13 and others who joined the party when it was first formed but did not get elected. All of these 13 originals elected representatives face the prospect of losing an election if polls are called, including Mahathir and Muhyiddin. This underscores the intensity of the elite party fight – and also suggests that they do indeed face an uphill struggle to keep the party electorally viable.

Real Bersatu? Real loyalties?

It is important to appreciate that Bersatu in parliament is now not the party was elected in 2018. Bersatu now claims to have over 30 MPs through two waves of defection – from Umno and from the Sheraton Move power grab, largely from PKR. The exact status of some of these MPs in the party is not certain, due to ambiguity around their membership and, for some, their loyalties. Rather than build the party through membership, the route was elite inducements.

Among these numbers of new entrants in Bersatu are Umno MPs – many not closely tied to Mahathir, but joined the party nevertheless. Many of these new entrants now hold key leadership positions in Muhyiddin’s cabinet and in Bersatu itself. It is however not clear whether their loyalties are to Bersatu or Umno or to themselves. The ambiguity of loyalty extends more broadly than inside Bersatu itself.

Be assured that those loyal to Umno recognise Bersatu as a threat to the electoral fortunes of their party and the fortunes of leaders in that party who they may or may not still be loyal to. There remains considerable resentment in some quarters in Umno over Bersatu in GE14 and the positions they still hold, as they continue to hold large shares of the cabinet. There is even more resentment of the new PKR entrants coming into (although not finalised) the Bersatu fold.

All rot or all for rot

As the battles for Bersatu and national government unfold, many are exhausted by the political theatre while others remain riveted. Bersatu’s divisions – like Umno’s in earlier decades – are shaping national politics in both similar and different manners.

Similar in the political and legal tools to engage in the challenge. Similar as the battle is predominantly personality-driven and testing loyalties and powers of persuasion and appetites for power. Similar in that the contest is expanding and the outcome yet unclear as there will be many skirmishes ahead.

Yet, this time and in these Bersatu-tied battles, the key difference is that the main party involved, Bersatu, faces its own elimination. Ironically, the party whose image Bersatu was made, Umno, and whose purpose was to challenge, seems to be making ground in terms of removing Bersatu as a political threat. Bersatu’s electoral future is precarious. The internal battles only worsen the party’s fortunes.

Given that Bersatu has always been a vehicle for the larger national battle – on who should govern Malaysia – it may not matter if the party survives as a party or in what shape the party survives. What will be important is who is the man occupying the top office in Putrajaya.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.