Young Malaysians are under siege. Covid-19 has created a perfect storm of economic, social, and political pressures that will have long-term implications for an entire generation of young Malaysians, and for the future of the Malaysian economy and society as a whole.

Economic hardships

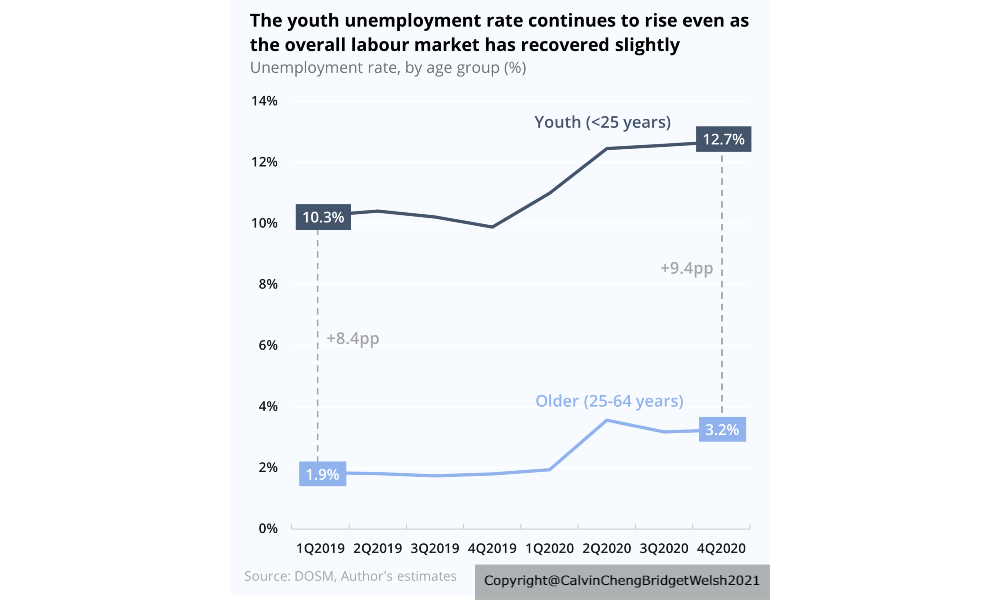

It is well-known that young Malaysians have been disproportionately affected by Covid-19. Overall, young workers have suffered far higher rates of job losses than older workers while also being pushed out of the labour market in record numbers.

The youth unemployment rate (for jobseekers below 25 years of age) is now at about 12.7 percent - far higher than the unemployment rate for older workers, which is sitting at about 3.2 percent.

Compared to a year ago, there are about 283,000 fewer young Malaysians who have a job, while about another 234,000 have exited the labour market entirely. Those who managed to hold on to their jobs are overwhelmingly more likely to have their work hours and/or wages cut and are also likely to face increased job precarity.

New Malaysian graduates entering the workforce only add to an ever-growing stock of unemployed youths, as bad labour market conditions and an uneven economic recovery continue to deepen the youth unemployment crisis.

Even when Malaysia’s economic growth returns to pre-pandemic levels, these economic pressures youth are facing will be stubbornly long-lasting. A large body of research warns that being unemployed while young for extended periods of time has sweeping long-term consequences for young workers, creating significant effects on future income, employment prospects, and mental wellbeing for decades down the road.

For too many young Malaysians, the inability to earn money now will affect their ability to have financial security over the long term, including the ability to purchase a home and comfortably take care of their families.

There is also evidence to suggest that elevated levels of youth unemployment can have important socio-political implications as well, leading to social unrest and higher crime rates.

Importantly, while youth unemployment may have been magnified by the pandemic - its roots run far deeper. There is a whole host of underlying structural inequities that younger workers face that have contributed to the pandemic’s disproportionate economic effects on Malaysia’s youth.

For instance, young workers, in general, are far more likely to have precarious jobs in demand-sensitive industries particularly vulnerable to the pandemic, along with persistently contending with higher rates of unemployment and underemployment.

In general, many youths are first-time labour market entrants and have yet to build the requisite information, social networks, and human capital to compete with the average experienced, older worker.

There is a misconception that Covid-19 is temporary. But unless ameliorated and addressed, the reality is that Covid-19 will indelibly shape the lives of Malaysia’s young cohort and the economic hardships they are experiencing now will extend far into the future.

Social issues

Beyond the burden of a pandemic-stricken economy, Covid-19 lockdowns have also generated underappreciated social ramifications for Malaysia’s youth. For younger Malaysians still in school, the shift to a full year of online schooling has been tumultuous.

For one, online schooling has laid bare the wide disparities between access to the internet and digital amenities between different households and regions. It is well-known that many underdeveloped or remote areas in Malaysia lack access to stable, high-speed internet - but access to sufficient internet-enabled devices per household have been impediments to learning too.

A family with two school-going children will require at least as many spare laptops/phones for each child to use for an entire day of online schooling - a luxury that many households cannot afford.

Online school has proven to be an inadequate substitute for many students. Recent research suggests that prolonged disruption of normal schooling can cause disproportionate learning losses for already-underperforming students and may increase the risk of students dropping out entirely.

Additionally, the second-order social impacts are even greater, especially for those without access to resources and adequate supportive social networks. In short, inequalities are widening as access to quality education is effectively being denied to those who need it most for social mobility and to provide for their families in the future.

Evidence shows the wellbeing of young people has also deteriorated since the onset of the pandemic. Many younger people, particularly adolescents, are increasingly susceptible to mental health issues like anxiety and depression as lockdowns have led to increased stress, uncertainty, and social isolation which are all especially disruptive for young people in their formative social years.

Worryingly, there are also cases of suicide among youth that reinforce the need to decriminalise suicide and to broaden access to counselling and support for children. Safety for children in schools and outside of schools urgently needs more attention.

Political side-lining

At the same time, already reeling from the economic and psychosocial impacts of the pandemic, young Malaysians are also increasingly denied political representation.

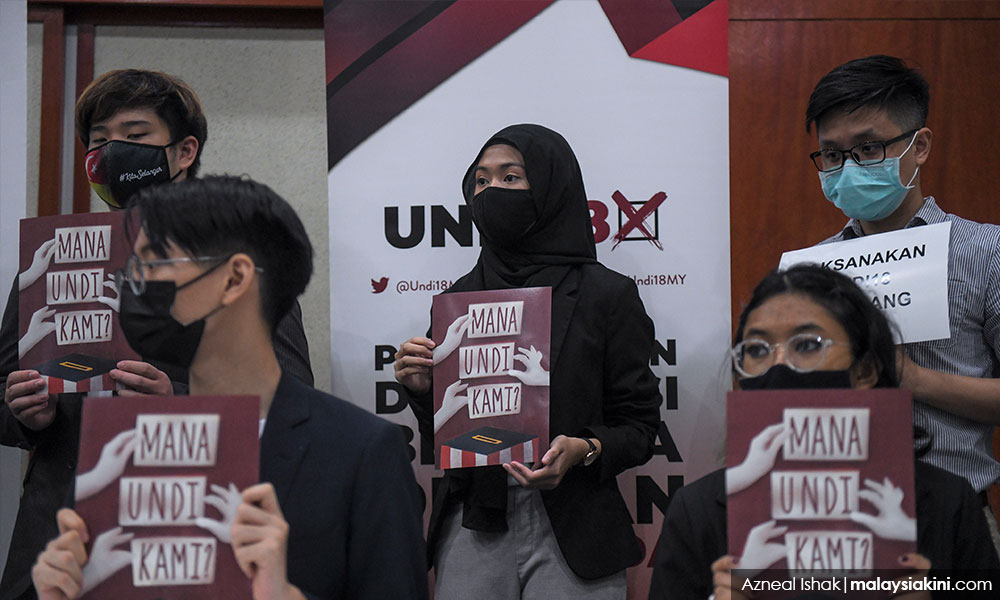

The government has delayed implementing the constitutional amendment to lower the voting age to 18 and confer voting rights to over 1.5 million young Malaysians; while youth-centric parties like the former youth minister’s Malaysian United Democratic Alliance (Muda) have been denied registration as a political party.

Statements from senior politicians over the past few months downplaying the struggles young workers are facing have only made matters worse. In response to rising youth unemployment and dwindling wages, cabinet ministers have repeated paternalistic narratives about the youth being "picky" and advising graduates to be "grateful" even if they barely make minimum wage.

No longer should young adults be treated like young children, disrespected, and their views and contributions ignored. Indeed, Malaysia’s youth have been politically side-lined for too long.

There is a need to change mindsets and recognise how outdated paternalism contributes to inequalities - a system that inherently marginalises the young in favour of age, experience, and patronage. In the next election, voters under 40 will be the majority (even with the delay in allowing voters aged 18 to 21 to vote.

One of the most important political developments of Covid-19 has been the growing political activism of the youth. Mobilisation in Thailand, Indonesia, and Myanmar may have captured headlines and inspired others with their bravery but in Malaysia, the same kind of frustration and discontent is growing.

Galvanised by the success of the youth-led Undi18 initiative and the important role that youths played in the election of the Pakatan Harapan government, youth dissatisfaction with political elites across parties is fundamentally changing national politics.

From speaking out on rape culture in schools to the recent Buka Puasa, Buka Parliament protest, youth political engagement has dominated the headlines and been the most decisive form of political mobilisation nationwide.

These changes are meaningful. The young are redirecting the narrative towards the challenges Malaysia is facing and stimulating productive discussions of solutions.

The youth-centric Parlimen Digital initiative is illustrative. Malaysians like Veveonah Mosibin and Ain Husniza Saiful Nizam who have managed to draw attention to important socio-economic issues of inequality and security to great effect are emerging as voices to make a better Malaysia, often overshadowing those of the political elites.

Covid-19 is a pivotal moment in Malaysian history. Denied a voice in Parliament, new voices are emerging and becoming increasingly prominent. The youth are leading. The economic, social, and political hardships that youths are facing cannot be ignored.

There need to be substantive policies to alleviate these negative effects and a more long-term vision to appreciate the structural challenges that Malaysia’s youth face. Without proactive measures, the continued marginalisation of youth puts Malaysia as a whole in peril. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur.

CALVIN CHENG is an Analyst in the Economics, Trade and Regional Integration programme at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (Isis) Malaysia, where his research interests centres around economic development and social assistance. He tweets economics and more at @calvinchengkw and can be reached at calvin.ckw@isis.org.my.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.