After race, the most common lens to interpret voting in Malaysia has been the rural-urban dynamic capturing geographic space and livelihoods.

Levels of urbanisation have been politically stereotyped with urban areas seen to be centres for opposition and rural areas captured by Umno/BN.

Given historic patterns of settlement of different communities, urbanisation levels have also traditionally been used as a proxy for race.

Today, urban areas are ethnically diverse, with Malays rather than Chinese comprising the majority in many urban areas. Levels of urbanisation have also increased, with over 70 percent of Malaysia now deemed as ‘urban’.

Importantly, along with societal changes, political alliances and affiliations have radically shifted. As such, there is a need to re-evaluate the relevance of the rural-urban dynamic for understanding voting.

This third article in the ‘Beyond Ethnicity’ series looks at how levels of urbanisation influenced voting in GE15, with special attention to Felda areas. The findings show that urban-rural considerations do continue to matter, although not to the same extent as they did in the past.

Of all the factors analysed in this special series for Malaysiakini – race, gender, age, urbanisation, and class (in the next piece), urbanisation has the least explanatory power in shaping voting.

We do however see important changes taking place in voting across levels of urbanisation and persistent differences in urban and rural voting patterns: over the last two general elections, rural areas are no longer strongholds for Umno/BN. Yet Umno/BN (now +GPS/GRS) still win over large shares of rural communities, especially in Borneo.

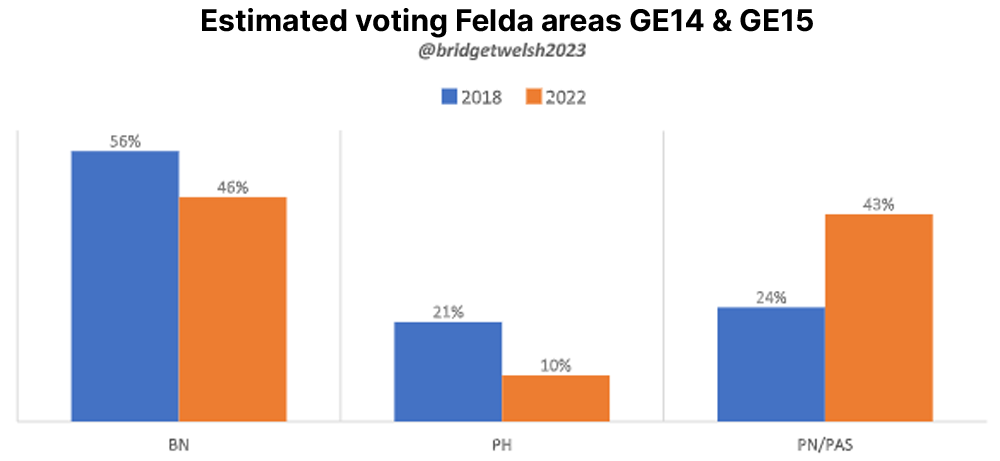

Despite Perikatan Nasional (PN)’s rising electoral strength and now dominance in rural areas as a whole, it is Umno/BN (+GPS/GRS) that won the most votes in Felda areas in GE15, for example.

In urban areas, however, Pakatan Harapan remains dominant but is facing greater challenges in its support compared to previous recent elections.

Understanding urban-rural divide in voting

Levels of urbanisation have been politically stereotyped. Early studies tied levels of urbanisation to race, a mindset that is still deeply embedded in politicians socialised before the 1980s.

This outdated view has limited scholarship that explores other factors why urban and rural areas vote as they do in more depth, including sources of information, personal networks, livelihoods, and the provision of services (and patronage) in rural areas.

Many analysts have also made the mistake of classifying seats – parliamentary constituencies - as either rural or urban.

With the exception of seats in Kuala Lumpur or rural areas in still remote parts of Sarawak, many ‘urban’ seats have rural areas (and vice versa) as well as in-between areas, what I originally labelled/pioneered in my work as ‘semi-rural’ areas over a decade ago.

To address the challenges of accurate analysis, my study draws from polling stations, classified as ‘urban, semi-rural/urban, and rural’ through fieldwork or local expert interviews.

Over two-thirds of the polling stations in the country are used for this analysis. Again, the method of ecological inference is used to estimate patterns of voting behaviour, for both turnout and support.

Persistent urban-rural differences

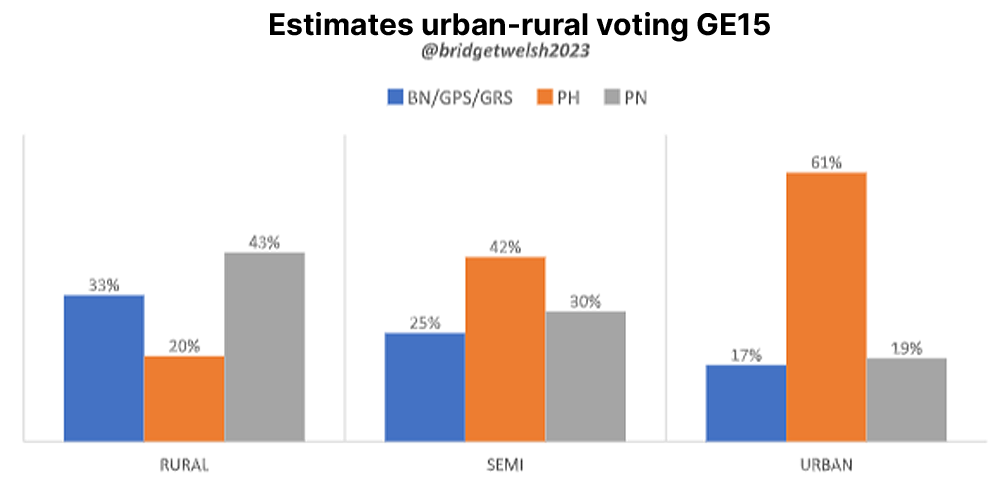

Here are the findings for GE15: Umno/BN’s support (including GPS and GRS from Borneo) in rural areas was double that of urban areas, while Harapan’s support in urban areas was triple that from rural communities.

PN follows Umno/BN, pipping that of Umno in both rural and semi-urban communities and on par with Umno in urban areas. From an urban-rural perspective, PN won over areas traditionally held by Umno/BN.

Despite the geographic divide between rural and urban areas being starker in Borneo, voting patterns by levels of urbanisation focused only on Borneo were not as wide as those in Peninsular Malaysia.

BN Sabah/GPS/GRS won an estimated 49 percent of rural areas, 50 percent of semi-rural areas, and 36 percent of urban areas.

Compared to other socio-economic factors that were weighted in their statistical impact on support, urbanisation only shaped an estimated 14 percent of voting, with other factors such as race and class considerably more important.

In terms of turnout, there was modest variation by levels of urbanisation nationally, with urban areas slightly lower at an estimated 71 percent turnout compared to an estimated 75 percent in rural communities. With regard to turnout, urbanisation differences were even less impactful.

The declining influence of the urban-rural divide on voting should not be a surprise, as it brings to light underlying drivers accounting for this division in voting that are also changing.

With greater internet coverage in more rural areas (although by no means enough), there is greater access to alternative sources of information. Also, with weaker political parties, patronage ties are weakening in rural areas, and changing as state governments take on more distributive roles.

The new generation of voters is less ‘grateful’ for the transformation that many rural areas credit BN in terms of better access to services/quality of life.

Many rural and semi-urban areas are particularly facing the problem of poor maintenance of facilities, from health to roads, and less favourable to credit incumbent governments like Umno/BN for services.

PN Felda shift

Rural and semi-rural areas however remain heated battlegrounds – and will be so in the coming state elections. One particular battle which I have regularly highlighted is Felda areas. Here I look at polling stations in Felda communities across Malaysia.

In GE15, Umno/BN held on to these areas, winning an estimated 46 percent of support, but just barely so. PN was close on its heels, winning an estimated 43 percent of support. PN made gains from both Harapan and Umno. Harapan lost an estimated 11 percent over the last two elections in Felda areas.

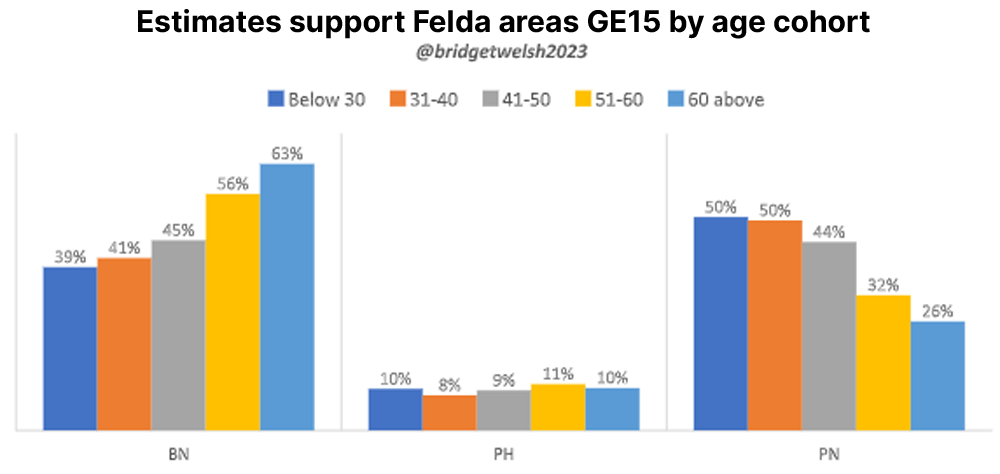

The findings clearly show there is a generation difference taking place in Felda communities, as found in my earlier studies. The young supported PN to a greater extent than older voters. This was reversed for Umno.

Harapan was not able to capture a significant share of Felda voters across age cohorts. While Umno may have had a slight advantage in GE15, it is towards PN where the trend favours for the future.

Policy gaps along urban-rural lines

From evolving Felda patterns shifting to PN to changes taking place in urban areas where PN is also making headway from Harapan, GE15 voting patterns along the urban-rural divide may not provoke any surprises beyond the declining influence on the voting of this social cleavage.

Varied support patterns and trends along levels of urbanisation, however, reinforce the need for the current government to have better policies to address the unique conditions of different communities.

So far, the Anwar Ibrahim government has just reinvented the Umno wheel for rural areas, continuing subsidies to farmers and fisherfolk in the hope that this will evoke support.

Umno continues to hold onto most positions in government bodies that address rural issues, including Felda, with minimal appreciation that its policies to promote social mobility have been failing for decades.

There has been scant attention to new (and sustainable) rural development policies, to the pressing need to fundamentally rethink how these communities can prosper as Malaysia’s economy becomes less competitive regionally.

A focus has been on digitalisation, sorely needed, but with major gaps in implementation. The most rural part of Malaysia, Borneo, is especially suffering the most from this lack of rural focus.

In the interim, Anwar has also cut opposition constituency allocations which disproportionately hurt rural communities that comparatively are more in need of these funds, especially in lower-income areas and with poor (and poorly maintained) infrastructure.

Also being left behind are Malaysia’s semi-urban areas, especially beautiful smaller towns/cities such as Taiping, Sibu, Kuantan, Batu Pahat, Kota Melaka, Kudat, and Kuala Perlis (to name just a few). There is no limited recognition of their challenges, from connectivity to capital investment.

For urban areas, there has similarly been inadequate attention to building transportation systems and ‘smart’ cities, despite more rhetoric on these issues. Urban areas, however, continue to be favoured in attention and revenue, as the spending on the MRT project shows.

While the urban-rural divide may not be as impactful in shaping voting as in the past, these voters do have their own voting patterns and the issues of their spaces, and their communities, require greater recognition of the unique challenges these different communities face. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute (Unari). She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.