There was a time I could say confidently, let politicians say what they will and drive the wedges between the races repeatedly to further their insidious intentions, the basic bonds between all Malaysians will hold and we will come together again.

I am not so sure anymore. I despair that a lack of interaction among our young caused by a number of factors, chief of which is declining educational standards and parochialism in the government education system, may make that quite impossible.

Unless we take drastic action now. First, some history.

There was a time not that long ago - no, it was long ago, a lifetime away - the early years after independence in 1957, the early 1960s when education at a government school was priced because it was the gateway to education and a better life.

And so, no matter who you were, Chinese, Indian, Malay and anything in between or beyond, the aspiration was to get a good education and grasp the opportunities for a better life through a higher-paying job.

Government schools provided the opportunity.

Winds of change

But things changed, the winds were gusting, driven by a flaming nationalistic fervour fanned by opportunistic politicians and an impatience for the pace to pick up. The unfortunate, probably partly planned, riots of May 13, 1969, hastened the process and Malay nationalism came to the fore instead of a multiracial one.

Frightened minorities barely put up a fight when crushing changes were imposed and control passed to bumiputera more quickly than they should have. Standards were lowered to push not only employment opportunities for bumiputera but also to fill educational vacancies with bumiputera too quickly.

The latter was what perhaps did the most damage as educational standards dropped too fast. In the eagerness to embrace the national language - Malay - English was cavalierly and indiscriminately discarded. We are now in danger of losing competence in the language to our utter detriment.

New Islamic consciousness fuelled by religious teachers returning from countries preaching a different brand of Islam who flooded back from overseas led to a push for Islamic values system-wide, including in schools.

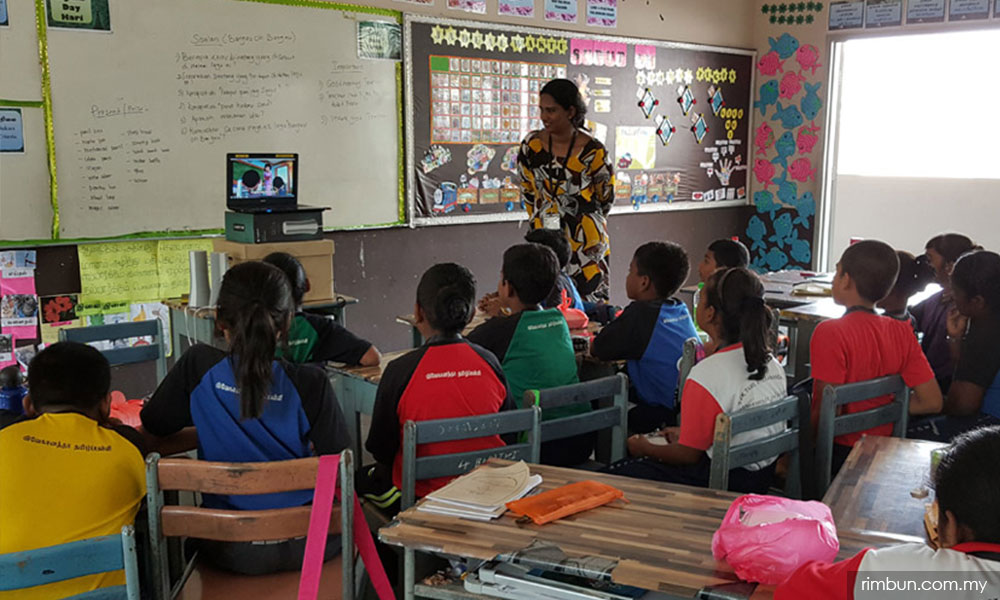

This, accompanied by the very palpable decline in teaching standards, caused primarily by a decline in teacher standards in government schools, spooked non-Malays and led to an exodus out of what was once the educational institutions of choice for all, giving rise to alternative systems in Mandarin, Tamil, Islamic and international schools.

By the late 1970s, this was happening already, with the tide turning to a flood in the 1980s, 1990s and beyond. An estimated more than 90 percent of Chinese in Malaysia now send their children to Chinese primary schools as indicated in this statement by a Chinese education group.

Malays were concentrated in the national education system and increasingly in religious schools. Indians split themselves between generally ill-equipped and poorly funded Tamil schools and national schools despite their shortcomings.

There is a different kind of change taking place. There is the rise of Chinese schools - a trickle now but could become a flood - which is attracting other races because of far better quality.

Exclusivity

And then there is a little forgotten segment - expensive private and international schools, some more costly than overseas education in top universities in terms of fees.

Here, the children of the elite - Malays, Chinese, Indians and others - mingle in truly multiracial form in a school system where the use of English predominates and values are far from Malaysian.

But they are divorced from contact with the needy and the poor, living in an idyllic cocoon of their own where everyone’s parents have plenty of money and students vie and compete over different kinds of things.

That’s another problem all its own where those embroiled have the means to sort it out themselves.

One can hope that things will change at the higher educational level but alas, it’s not so. A quota system in all government universities and an exclusively bumiputera institute, Universiti Teknologi Mara or UiTM, have further polarised education.

UiTM is massive. According to its website, it has a gigantic enrolment of 180,000 students (yes, that’s right) and has over 500 academic programmes, making it the largest comprehensive university by far in Malaysia and large even by world standards.

But when it restricts entry to bumiputera, it promotes racial polarisation.

Thus non-bumiputera who can afford it gravitate to private universities which have the great advantage that their degrees are better recognised.

This widens the gap between bumiputera and others, especially since standards have dropped precipitously in public universities. Graduate unemployment, especially among Malays, has soared.

How can such an education system do anything but polarise races and cause disunity? The public education system has failed as a tool of national integration, ruined by overzealous politicians who still can’t see the forest for the trees.

Restoring quality

Is there a solution to this truly horrific situation? Do you have one?

I can only speak in the most general of terms but that has to be the case for vast, seemingly insoluble problems. While alternative school systems may offer respite, the only viable way is to restore the quality of public schools and universities to previous levels and beyond, more easily said than done.

Handle the basics first - get primary education rolling - train new teachers who are good and retrain the old ones. Cut class sizes and revamp the syllabus.

And yes, reduce the emphasis on religious education - leave that to the parents. Extend this to the secondary schools and then on to the universities.

How does one do this? Consider each school to be a corporation. Get a good CEO (headmaster or headmistress). Empower him/her, if not to hire then at least to sack, to raise funds, to assess each teacher under his watch and set key performance indicators (KPIs) for them.

Train your CEOs - intensive courses during school breaks and ongoing courses during alternate weekends. Encourage them to crack the whip to set standards for his teachers, including KPIs, watch them, encourage them, motivate them and work with them.

We all know the power of the CEOs to change the course of companies. Do the same for HMs and the schools. And then move a step forward and do that for all public universities - great vice-chancellors, professors and lecturers. Import judiciously if necessary.

And for God’s sake, depoliticise education and use all the expertise from all races. This is the most dire of emergencies after all with far-reaching effects that will eventually affect each and every Malaysian one way or another.

And how long will it all take? To improve headmasters and teachers - five years at least. To flow this up into higher education in the form of competent students, another five years. And then to produce a new crop of great students at primary and secondary level, 10 years at least.

Give or take 20 years - the same time it took for us to ruin one of the best education systems in Asia at one time. A start has to be made somewhere. We are fast running out of time.

For all this to happen, we need exceptional education and higher education ministers. Oh, that would require a fantastic, brave prime minister who is prepared to push limits and boundaries to achieve the impossible.

Ah, we can hope, can’t we? - Mkini

P GUNASEGARAM, a former teacher, says that education is one area we must not tinker with lightly, as we are now finding out.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.