In the 1990s and the noughties, a sign of progress and development was to make a big statement by building large, tall buildings.

Malaysia joined that bandwagon with the Twin Towers and still has not quite got over that old obsession, as we have yet another in the form of TRX.

But it is time to move on and start building the city of the future for the eight million residents of Kuala Lumpur. We need more high-rise buildings with cavernous underground car parks like a ballet dancer needs his toes amputated.

We need something very different, a city that rewrites the books on how tropical cities should be made truly liveable. A tropical city where the improvements in the quality of life are akin to a smoker needing a fresh pair of lungs.

and largest Botanical Metropolis, one where if you wanted to you could walk uninterrupted in leafy and shady botanical corridors rich in biodiversity from Petaling Jaya to Bangsar to Brickfields to the Central Market.

Imagine a city with 25 such corridors and many other minor botanical pathways which also serve as feeder walkways from light rail transit stations to residential areas such that you would not need a cab to get home.

All of this is possible and achievable in 20 years. The good news is that there is a champion for it. In a recent speech, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim remarked that tall buildings are not enough for Kuala Lumpur to be proud of.

In his view, there is a need for more parks and other people-centric amenities. He is right, and there is a real need to turn his vision into reality, or we risk making many parts of this city into hot concrete monoliths as climate change takes hold.

The vision of making Kuala Lumpur the world’s first botanical city is that and much more. It is not about parks dotted across the city as glamourous landscaping projects, but a gigantic natural park that spreads like a healthy symbiotic fungus across the Klang Valley and plays several critical roles in this era of climate change and diminishing natural areas in urbanities.

The need for people to be in contact with nature for their well-being is more important than ever.

Making it a reality

Kuala Lumpur’s botanical richness has long been recognised as one of the greatest characteristics of the city. Anyone who has had a view of the Klang Valley from the top of the KL Tower will immediately be aware that the city is surrounded by lush forests.

Sadly, we had an era extending over half a century during which we paid little attention to the damage of unrestrained development. Many of us have woken up to all the ills that modern-day urbanisation has inflicted upon us.

But it does not have to be this way and the next 20 years should be committed to reversing the damage and thereby building the global blueprint for designing and running tropical cities.

So more than ever, this grand vision is about reclaiming the city’s botanical roots while seizing one of the most acute developmental opportunities for the people of Kuala Lumpur.

This is not some new-age hippy endeavour. It is an opportunity to leverage the latest advancements in nature-based solutions for urban planning and living.

All it needs is foresight and the will to ensure the arrangement, health, and type of vegetation can be managed with competence by public bodies with support from the communities who will be the ultimate stewards of this botanical park.

Yes, money will be needed but there are many ways to overcome this, including building public-private partnerships as well as redirecting funds allocated to expensive showcase parks towards this vision.

The transformation into the world’s first “Botanical City”, will also create a slew of new job opportunities, open new areas of research and development, improve public health, increase tourism, provide low-cost climate change mitigation strategies, and enable entirely unique urban designs.

It will also compel changes in how our surface waterways are managed and provide opportunities to solve several age-old urban conundrums. Part of this will be putting in place a comprehensive sewage treatment system with a target of zero discharge of pollutants to all surface waters creating even more jobs.

Imagine being able to sit in the shade of a botanical corridor along the banks of the Klang River and not be overwhelmed by noxious odours while having satay and noodles. If Tokyo, Seoul, and Singapore could do it, so can Kuala Lumpur.

Very importantly, it will be an opportunity to help change the mindsets of the population and allow them to become the proud “citizen-stewards” of this unique botanical city. Who needs eco-warriors when everyone is a botanical citizen?

Extensive greenery

What does this Botanical City vision look like? It is one that incorporates extensive greenery – not just ornamental plants - and plant life into all aspects of urban planning as a tool, and not just an aesthetic afterthought.

It is not about developers being compelled to build little parks adjacent to buildings and planting a few trees to compensate for the planned destruction of forested areas, even if they are secondary forests.

And it is not about the facile greening of facades and expensive parks built on rooftops of multibillion ringgit buildings. Here are several aspects that can be used to frame the development of the Botanical City, and these will be subject to consultation with all stakeholders:

No further developments that result in a net loss of nature or reduction in green spaces. Geographic information system technology can be easily used to manage this, and political will is all that is needed to implement it.

Multistakeholder commitment to the protection and preservation of all existing botanical gardens, parks, and green spaces. Zero tolerance for indiscriminate removal of the aforementioned.

Growing a well-designed web of botanical corridors across the Klang Valley, all of which are connected and allow residents to access recreation and other reasons to walk long distances without having to leave the corridors.

Cultivating only native species from all over the country and served by a highly qualified team of scientists. An opportunity to build a world-class centre for the study of tropical rainforest protection and a gene pool of diminishing botany - right in the heart of the Klang Valley.

High integration of green cover with clear tree canopy targets.

Minimum 600 sq m of publicly accessible green space per person and every citizen to have access to green space within five minutes of their home.

Efficient water conservation and wastewater management strategies using vegetation.

Increased walkability and public transport interconnectivity.

Stringent laws and enforcement on cutting, logging, and damage to urban trees and forested areas.

The use of all vacant spaces into mini community parks or gardens including turning large roundabouts into mini botanical gardens.

Reaping the rewards

Malaysia’s botanical richness is simply not thought about at this level of utility yet. It has instead been thought of as a hindrance to development.

Of course, Kuala Lumpur’s trees have made the news recently, but not for the right reasons: with the recent wave of tropical thunderstorms, there have been incidents involving uprooted trees, which in one case tragically resulted in the death of a motorist.

However, this should not be seen as a signal to further reduce tree cover in the city. It should be used as an opportunity to revamp the role that Kuala Lumpur’s botanicals tangibly play in improving people’s quality of life - and not just for aesthetics.

The prime minister clearly understands this. In response to the recent uprooting of trees, he has “instructed the mayor that for every tree that has to be cut down, 100 new trees must be planted.”

Let us have a master plan and use the vision of the Botanical City to achieve these targets and more.

The prime minister’s statement is backed by extensive reasoning. Malaysia has reached record-high temperatures and is now slated as the seventh-hottest city in Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur is experiencing an ever-rising urban heat island effect in the range of four to six degrees Celsius.

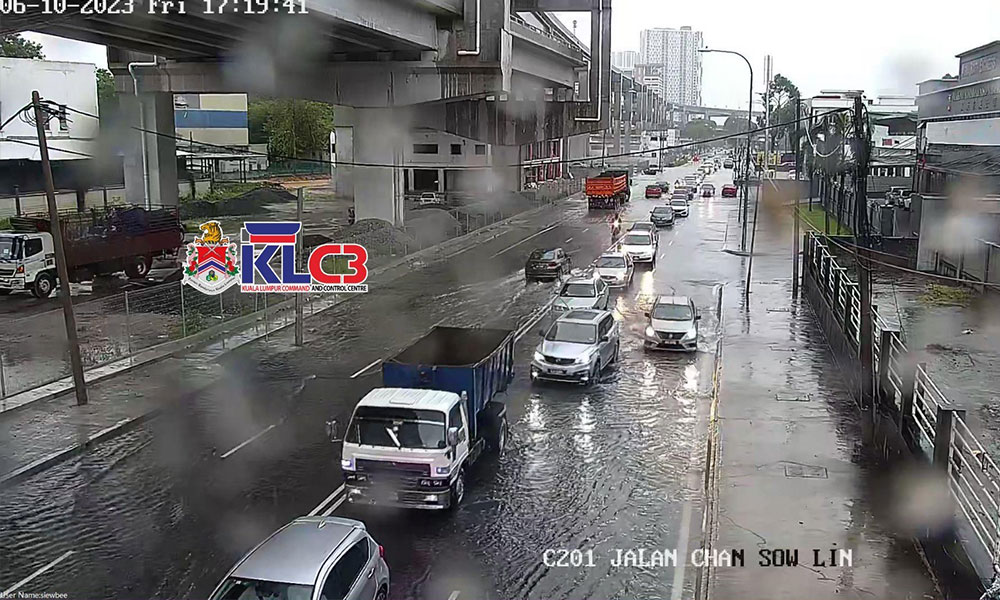

The federal capital has also seen a significant rise in the frequency and intensity of flooding and landslides. We have the opportunity to make it the coolest - in more ways than one - tropical city in the world with this vision.

These impacts are connected. With more concrete, more tarmac, fewer trees, poor drainage systems, and less soil, the lag time between rainfall and flooding is dramatically reduced. In addition, heat is being reflected to make outdoor life very uncomfortable.

Public health benefits

The answer cannot be more air-conditioning. Water bodies are more readily polluted. Air quality is becoming worse without the filtering effect of tree leaves - during times of haze, spending a full day outside is the equivalent of smoking nine cigarettes.

Clearly, there are numerous public health benefits to a Botanical City and that should be a key driver for change. Tree cover can lower the temperature of the city by several degrees, while leaves clean the air and roots filter groundwater.

By now, we all know Malaysia is the most overweight country in Asean, due in part to the populace’s dislike of walking between locations due to intense heat. Tree cover, combined with well-maintained walkways, provides the most cost-effective way of encouraging a more pedestrianised and walkable city.

Foliage also provides cost savings. Green spaces absorb rainwater, thereby mitigating flood risks and helping to prevent damages to public and private property.

Green roofs and walls provide natural insulation and reduce the costs associated with the energy consumption needed to keep the building cooler – one North American study found foliage reduced energy use in cities for cooling by 7.2 percent.

Climate change resilience

Then there is the element of drawdown of carbon dioxide. Given that Malaysia’s greenhouse gas emissions have experienced an 11,632 percent increase since 1991, a Botanical City would serve as a testament to the government’s aim for net zero emissions by 2050 and improve Malaysia’s resiliency against climate change.

Large companies with significant carbon footprints like Petronas can be invited to invest in various parts of the botanical city with the possibility of even earning carbon credits depending on the scale and other specifics of their involvement.

A Botanical City would even enhance national food security. Malaysia already possesses the agri-tech needed for rooftop and vertical farming, and efforts to expand its usage are underway.

To position Kuala Lumpur as a food hub, additional incentives can be sanctioned to implement the technology throughout the city and not simply resort to buildings.

Ample amounts of poorly utilised land can be absorbed into these botanical corridors in which food is also grown. It requires imagination, efficient management, and importantly, can create jobs.

Communities can be encouraged and organised to grow certain vegetables and fruits and these areas can also be integrated into the web design of inter-connected botanical corridors.

This then stimulates the agri-tech and horticulture industry. By zoning in on fresh, locally sourced, and ethically farmed produce, Kuala Lumpur and the Klang Valley as a whole can begin to move towards some degree of self-sufficiency and fortify itself against shocks in the food supply chain.

Leafy neighbourhoods also push up property prices. There is added aesthetic value from greenery in densely grey urban areas.

Take Desa Parkcity, for instance. There are vibrant parks, designated pedestrian walkways and trees line the streets, making it extremely walkable and cooler. The cheapest Desa Parkcity property currently on the market is valued at RM570,000, while their larger properties can go up to at least RM12.5 million.

There’s a clear financial incentive, but richer segments of Kuala Lumpur shouldn’t be the only ones to benefit from this.

Let’s get started

The process of transforming Kuala Lumpur into a Botanical City would create tens of thousands of jobs for the public and private sectors alike, from urban designers to arborists, scientists, nurseries, gardeners, composting firms, construction companies to sanitation planners, engineers, and technicians.

If advertised properly, it will undoubtedly become a tourist attraction – simply look at Singapore’s “City in a Garden” vision. Kuala Lumpur can create its own unique model for a tropical city, which can be used as inspiration for other cities around the world.

More than 1.3 million trees were planted throughout Penang in conjunction with Earth Day 2024 – in just one day. Why can’t this be emulated in KL, on a regular basis? To turn Kuala Lumpur into a Botanical City would probably require several million trees to be planted over a period of a decade.

We can do this. Get started.

Realising the Botanical City vision will take a great deal of organisational competency on behalf of the city and federal government. But the key is having a vision and the political will.

Transparent public investment will have to ramp up. New regulations will have to be established to prevent the continuing degradation of the city’s natural environment, while incentives will need to be provided to encourage the private sector to co-create the Botanical City vision alongside the government.

To manage this process, a new government body could even be created – the Department for Botanical Cities – a world-first in creating the cities of the future. To kick start it a pilot area should be identified as the hub where the seeds of the Botanical City are planted and from where it blooms across the Klang Valley over the next 20 years.

Lessons will be learnt, and these will help build new insights and skills.

These changes are entirely possible. Malaysia is located at the heart of one of just three rainforest regions in the world, and this is without doubt one of the country’s greatest competitive advantages.

Yet it seems this is only understood in the context of the agricultural and extractive industries. When it comes to integrating this advantage into our cities, greenery must move beyond an aesthetic luxury for rich communities to become a fundamental part of the urban fabric.

With the right leadership, Kuala Lumpur can establish itself as a pioneer in urban innovation and environmental stewardship as a Botanical City, and benefit residents and the economy simultaneously. - Mkini

CHANDRAN NAIR is the founder and CEO of Global Institute for Tomorrow and the author of “Dismantling Global White Privilege: Equity for a Post-Western World”.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.