THE idea that wars could be fought not only with bullets and missiles but through rain, drought, and manipulated rivers may sound like science fiction. However, history and contemporary conflicts demonstrate that environmental systems have long been viewed as strategic tools of warfare.

Weather modification and water weaponisation challenge established norms of international law and ethics, while posing serious risks to civilian populations.

For Malaysia, a country increasingly exposed to climate volatility, flooding, and water stress; ignoring these unconventional forms of warfare would be a strategic blind spot.

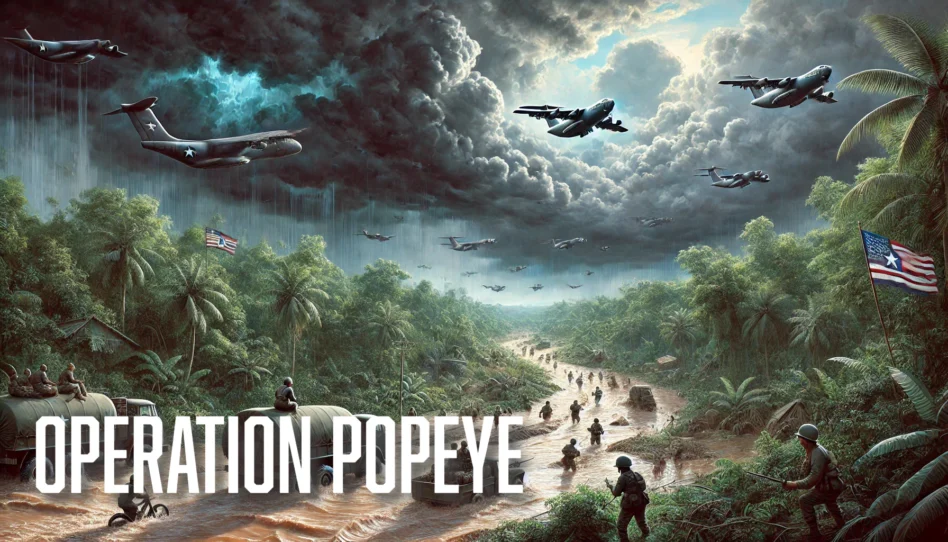

One of the clearest historical examples of weather warfare was ‘Operation Popeye’ during the Vietnam War between 1967 and 1972. The United States conducted a covert cloud-seeding programme aimed at extending the monsoon season over key supply routes used by North Vietnamese forces.

By inducing heavier and prolonged rainfall, the objective was to turn roads into mud, flood river crossings, and disrupt logistics without direct battlefield engagement.

Although the tactical effectiveness of the operation remains contested, its exposure shocked the international community and revealed that weather modification was not merely theoretical, but operationally deployed.

This episode ultimately led to the adoption of the 1977 United Nations Environmental Modification Convention (ENMOD), which prohibits the hostile use of environmental modification techniques.

Despite ENMOD, the strategic temptation to manipulate environmental systems has not disappeared.

Technological advances in atmospheric science, climate modelling, and geoengineering have revived debates about whether weather can be shaped deliberately for strategic advantage. The danger lies not only in intentional use, but in the dual-use nature of these technologies.

Civilian cloud-seeding programmes intended for drought mitigation or agricultural support can, under different circumstances, be repurposed or perceived as hostile acts.

Weather systems are inherently unpredictable, and any attempt to weaponise them risks unintended cross-border and long-term ecological consequences.

Closely related to weather warfare is the concept of ‘water weaponisation’, which has a much longer and more visible history. From ancient sieges that poisoned wells to modern conflicts where dams, canals, and water treatment facilities are targeted, water has repeatedly been used as a tool of coercion.

Recent wars have highlighted how controlling or destroying water infrastructure can cripple civilian life, undermine food production, and destabilise entire regions.

Unlike weather manipulation, water weaponisation is often more direct and immediately observable, but its humanitarian consequences can be equally devastating.

A comparative view of weather warfare and water weaponisation reveals important distinctions. Weather warfare relies on atmospheric interventions: cloud seeding, aerosol dispersal, or climate modification technologies whose outcomes are uncertain and often uncontrollable.

Water weaponisation, by contrast, focuses on tangible infrastructure such as dams, reservoirs, and rivers, making its effects more predictable but no less destructive.

Legally, ENMOD explicitly bans hostile environmental modification, while attacks on water infrastructure are governed by international humanitarian law, particularly rules protecting civilian objects.

Yet enforcement in both areas remains weak, especially in conflicts involving non-state actors or grey-zone strategies.

For Malaysia, these issues are not abstract. The country’s geography and climate make it highly dependent on predictable monsoon cycles, stable river systems, and functional water infrastructure. Flooding, landslides, and drought already impose heavy economic and social costs.

In such a context, any deliberate interference whether through hostile weather modification or attacks on water systems would magnify existing vulnerabilities.

Moreover, Southeast Asia’s interconnected climate systems mean that environmental disruptions in one country can easily affect its neighbours, increasing regional instability.

Malaysia’s critical infrastructure further amplifies these risks. Hydroelectric dams, irrigation networks, and urban water treatment facilities are essential to national resilience.

Disruption to these systems whether through kinetic attacks, cyber interference, or environmental manipulation could quickly escalate into food insecurity, energy shortages, and social unrest.

In an era of hybrid warfare, where state and non-state actors exploit non-military domains to achieve strategic goals, environmental systems represent an attractive but dangerous target.

Geopolitically, Malaysia operates in a region where major powers are increasingly active, and where competition often unfolds below the threshold of open conflict. Advances in climate science and weather technology among global powers raise legitimate concerns about transparency, trust, and intent.

Even the perception that a state is manipulating weather or water resources could inflame tensions. Malaysia must therefore approach this issue not only as a defence concern but as a diplomatic and governance challenge.

Rather than pursuing any form of offensive environmental capability, Malaysia’s strategic response should prioritise resilience, law, and cooperation. Strengthening domestic legal protections for water and environmental infrastructure is essential.

At the international level, Malaysia should advocate for stronger monitoring and confidence-building measures related to weather modification technologies, building on the principles of ENMOD.

Transparency and data-sharing can reduce suspicion and prevent misinterpretation of civilian environmental programmes.

Investment in climate resilience and early-warning systems is equally crucial. Robust meteorological monitoring, flood management infrastructure, and water governance reforms can reduce the impact of both natural and deliberate disruptions.

By strengthening its adaptive capacity, Malaysia makes itself a harder target for any form of environmental coercion.

Finally, regional cooperation is indispensable. Environmental systems do not respect national borders, and neither do the risks associated with their manipulation.

Malaysia should work within ASEAN to develop a regional framework on environmental security, encompassing shared data, joint responses to extreme events, and collective norms against the weaponisation of weather and water. Such cooperation would not only enhance security but also reinforce regional trust.

Weather and water are foundational to human survival and economic stability. When they are turned into instruments of warfare, the consequences are indiscriminate and enduring. History shows that environmental manipulation is not a theoretical danger but a demonstrated reality.

For Malaysia, acknowledging this risk and preparing accordingly is not alarmism but it is prudent statecraft in an era where climate and conflict are increasingly intertwined.

R Paneir Selvam is the principal consultant of Arunachala Research & Consultancy Sdn Bhd (ARRESCON), a think tank specialising in strategic national and geopolitical matters.

The views expressed are solely of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of MMKtT.

- Focus Malaysia.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.