History is not merely a record of significant past events; it is the collective memory of a nation - the repository of its struggles, achievements, values, and aspirations.

In a plural society such as Malaysia, history plays an especially critical role in shaping national identity, fostering mutual respect, and cultivating a shared sense of belonging.

When history is told truthfully and inclusively, it strengthens patriotism and unity. When it is selective, distorted, or exclusionary, it fractures society and undermines trust between communities.

History should reflect what truly happened, not what we wish had happened. It must be told with intellectual honesty and grounded firmly in evidence.

A mature nation does not fear historical complexity. Rather, it embraces nuance, acknowledges uncomfortable truths, and recognises that national strength lies not in myth-making but in moral and intellectual integrity.

As the late historian Zainal Abidin Wahid wisely reminded us in his professorial inaugural lecture at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia on Jan 22, 1991: “Students in schools must be nurtured and educated with history grounded in truth. The truth, at times, may indeed be bitter to accept. Nevertheless, it is essential to be known.”

The importance of history is well established. First, it explains how the present came to be and provides insight into the social, political, and economic structures that shape contemporary life.

Second, it helps individuals and communities develop a sense of identity rooted in continuity and context.

Third, it enables societies to learn from past mistakes and engage more wisely with present and future challenges. As Spanish philosopher George Santayana famously warned, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Fourth, history cultivates critical thinking by requiring analysis of causes, consequences, and significance based on evidence rather than ideology.

For Malaysia, these functions of history are not abstract ideals. They are urgent necessities.

Selective memory crisis in Malaysian history

Malaysia’s official historical narrative - particularly as conveyed through school textbooks - suffers from serious omissions, distortions, and imbalances.

These shortcomings are not merely academic; they have profound implications for national cohesion, inter-ethnic relations, and the development of informed citizenship.

Concerns about selective memory in Malaysian history education have prompted growing public debate among scholars, educators, and citizens alike.

In this context, my recent book, “Forgotten Malaysian History: Restoring Voices and Reclaiming Truths”, represents one contribution to a broader effort to encourage more balanced, evidence-based engagement with the nation’s past.

The book brings together themes that are rarely examined comprehensively in a single volume: early civilisations, indigenous histories, migrant communities, whose members today are proud citizens of Malaysia, constitutional debates, the May 13 Incident, the evolution of citizenship, and the contributions of lesser-known nation-builders.

It draws on authoritative sources - colonial records, census data, archival materials, and scholarly studies - while remaining accessible to the general reader.

Equally important is its inclusive tone. Its purpose is to illuminate, contextualise, and encourage understanding and mutual respect grounded in historical evidence.

Orang Asli marginalisation

One of the most serious deficiencies in Malaysia’s historical narrative is the marginalisation of the Orang Asli.

As the indigenous inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia, Orang Asli communities predate all later populations, including the Malays.

Archaeological findings, anthropological research, and linguistic evidence consistently demonstrate that they have inhabited the peninsula for thousands of years.

Yet, in contemporary secondary school history textbooks, the Orang Asli are largely absent from the national story. No explicit acknowledgement of their status as the original inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia is made.

This is particularly striking given that they were clearly recognised as “penduduk asal Tanah Melayu” in our history textbooks of the 1970s.

In contrast, the Form Four history textbook (2019, page 225) states that the Malays are the “rakyat asal Tanah Melayu”. Such an omission denies the Orang Asli their rightful place in the nation’s historical narrative.

Equally problematic is the persistent conflation of “indigenous inhabitants” with later political dominance.

Indigenous inhabitants are those whose presence predates recorded migrations and state formation, with demonstrable continuity across millennia. By this definition, the Orang Asli are the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia.

Recognising this historical reality does not diminish any other community; rather, it restores conceptual clarity and historical accuracy.

Malays as Peninsular Malaysia’s ‘definitive people’

The Malays occupy a central and defining position in the history of Peninsular Malaysia, but this role must be understood with precision.

Historical evidence indicates that Malays emerged in the peninsula through complex processes of migration, cultural assimilation, intermarriage, and political consolidation from the first millennium CE onwards.

To acknowledge that Malays were not the earliest inhabitants is not to question their legitimacy or importance; it is simply to recognise historical evidence.

The Malays are best understood as the “definitive people” of Peninsular Malaysia. A definitive people are a dominant community that has shaped the political order, cultural norms, language, governance, and identity of a land through sustained state formation and civilisational influence.

Through the establishment of Malay polities, the spread of the Malay language as a lingua franca, the development of adat, and the formation of Malay-led states, the Malays have shaped the enduring political and cultural character of the peninsula.

This distinction - between indigenous inhabitants and definitive people - allows Malaysian history to be narrated with nuance rather than ideological simplification.

It affirms the historical primacy of the Orang Asli while recognising the foundational role of the Malays in shaping Peninsular Malaysia’s identity.

Clarifying the ‘pendatang’ narrative

Few terms have caused as much harm to national cohesion as “pendatang”.

In public discourse, it has been used to label entire communities - often Malaysians whose families have lived here for generations, including the Baba-Nyonya, Malacca Chettis, and Portuguese Eurasians - as outsiders or immigrants.

Historical scholarship shows that migration is a universal human experience, including that of the Malays themselves, while constitutional citizenship is a separate and decisive legal status.

Based on authoritative research, the Malays have historical migration roots in Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and other neighbouring islands.

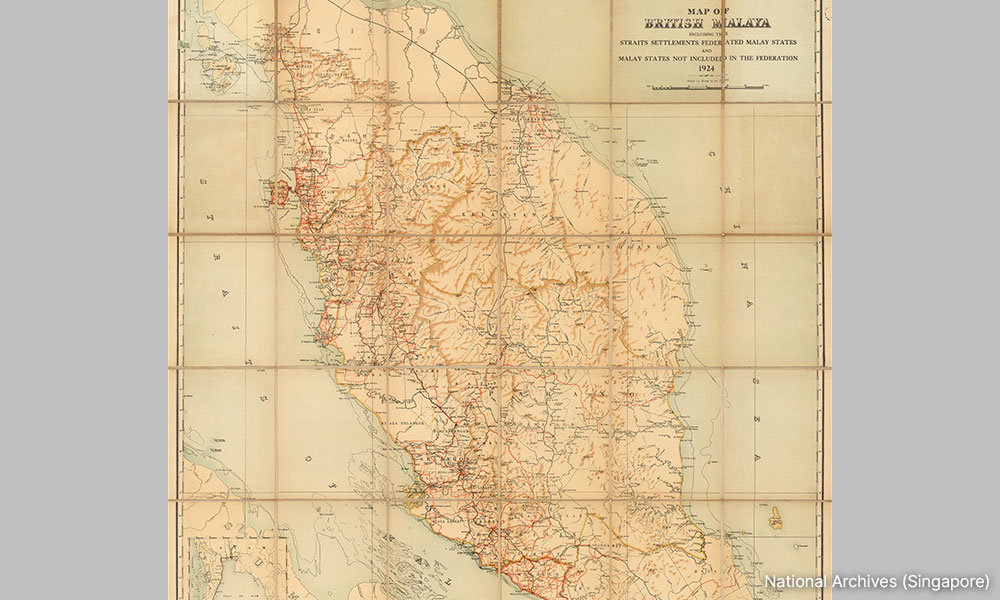

According to CA Vlieland, the Superintendent of the 1931 Census of British Malaya, and other leading authorities, including Rupert Emerson and Alexander K Adelaar, most Malays who migrated to the Malay Peninsula trace their origins to Sumatra.

Indeed, Parameswara himself, the founder of the Malacca Sultanate, was a refugee prince from Palembang, Sumatra.

Interestingly, in 2013, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, then the home minister, reportedly declared that “over half of Malayan ministers are of Indonesian descent” (Antara, Sept 2, 2013).

The Chinese, Indian, Eurasian, Ceylon Tamils, and other communities were not passive arrivals but active participants in nation-building - developing mines, plantations, towns, schools, hospitals, trade networks, and civic institutions long before independence.

As the late eminent historian Professor Emeritus Khoo Kay Kim rightly emphasised, we are all citizens of Malaysia, and none of us should be labelled as “pendatang”.

Anyone who holds Malaysian citizenship cannot be deemed a pendatang; by definition, a pendatang is not a citizen (Malay Mail, June 1, 2019).

Forgotten builders and erased contributions

Another serious distortion in Malaysia’s national narrative is the systematic downplaying of non-Malay contributions to nation-building.

Few examples illustrate this more starkly than the treatment of Yap Ah Loy, the third Kapitan Cina and builder of Kuala Lumpur.

Historical records - British administrative reports, contemporary accounts, and municipal documents - clearly establish Yap Ah Loy as the key figure who transformed a struggling tin-mining settlement into a functioning town.

He constructed roads, markets, and public infrastructure, maintained order during periods of conflict, and led the rebuilding of Kuala Lumpur after its devastation during the Selangor Civil War (1866-73) and the fire and flood of 1881.

Without his leadership, Kuala Lumpur might not have survived to become the capital city of Malaysia.

Yet in our school textbooks, Yap’s role has been reduced, diluted, or stripped of its foundational significance. This revisionism does not elevate any other group; it merely erases historical truth.

A nation secure in its identity should have no difficulty acknowledging the achievements of those who contributed decisively to its urban and economic development.

The marginalisation of South Indian contributions represents another major omission. South Indians played an indispensable role in developing the rubber industry, which formed the backbone of Malaya’s colonial economy.

Beyond plantation labour, South Indians were deeply involved in infrastructure development, including the construction of roads, railways, bridges, drainage systems, hospitals, and public buildings.

Historical estimates suggest that more than 750,000 Indians lost their lives in the arduous process of opening up treacherous jungle tracts for rubber cultivation and infrastructure development.

They also served as clerks, teachers, hospital assistants, surveyors, and technicians, contributing significantly to the administrative and social foundations of modern Malaya.

Yet their historical presence is often reduced to a narrow and decontextualised portrayal of estate labour, detached from the broader narrative of economic development and nation-building.

To forget these contributions is to forget how Peninsular Malaysia was physically built.

Parameswara, Malacca, and the distortion of early history

The misrepresentation of Parameswara, the founder of Malacca, further illustrates the problem of myth supplanting evidence.

The 2017 Form Two history textbook (page 82) perpetuates the long-disputed myth that Parameswara converted to Islam in 1414 and adopted the name Megat Iskandar Shah.

However, reliable sources from Ming Dynasty China, specifically the Ming Shih-lu, unequivocally show that Parameswara and Megat Iskandar Shah were father and son.

Closely related to this distortion is the systematic downplaying of Hindu-Buddhist civilisation in the Malay Peninsula.

Up to the 14th century CE and before Islamisation, the peninsula was deeply embedded in the Hindu-Buddhist cultural world of South and Southeast Asia.

This influence is evident in political concepts of kingship, legal traditions, art, architecture, language, and ritual practices. Sanskrit inscriptions, archaeological remains, and early texts testify to a rich pre-Islamic civilisational layer.

Acknowledging this heritage does not weaken Malay history. It strengthens it by demonstrating continuity, adaptability, and cultural sophistication.

To erase or minimise this period impoverishes the national narrative and deprives Malaysians of a fuller understanding of their civilisational roots.

Reclaiming the Malaysian story

Restoring balance to Malaysia’s historical narrative requires deliberate and principled reform.

First, history textbooks must be written by qualified historians drawn from diverse ethnic backgrounds, possessing a broad and integrative understanding of Malaysian history rather than a narrow specialisation within a single subfield.

A plurality of perspectives enhances accuracy and guards against ideological bias.

Second, Form 1-5 history textbooks must be subjected to rigorous peer review to ensure factual accuracy, internal consistency, objectivity, and evidentiary balance. History education should not be a vehicle for political messaging but a discipline grounded in evidence.

Third, history books should be devoid of value judgments and moral labelling. The role of the historian is to explain, contextualise, and analyse - not to glorify or vilify.

Fourth, the national narrative must adequately reflect the whole federation, including East Malaysia.

A peninsular-centric framework distorts national history and marginalises Sabah and Sarawak, whose histories are integral to the Malaysian story.

Fifth, the teaching and learning of history must move beyond rote memorisation. It should cultivate deep learning, critical thinking, information literacy, and communication skills.

Students should be trained to analyse sources, assess evidence, and engage thoughtfully with competing interpretations.

Finally, history should be taught in a lively and engaging manner using diverse instructional strategies. Students should not be passive recipients of information, but rather active participants in historical inquiry.

Working with primary sources, oral histories, and local narratives reconnects national history with lived experience and community memory.

A new year reflection for 2026

National unity cannot be built on selective memory of a nation’s past or historical denial. Only through honest engagement with the past can patriotism be deepened, unity strengthened, and the foundations of a just and inclusive nation secured.

As Malaysians enter 2026, the appeal is simple yet profound: to think and act as Malaysians - not as fragmented identities inherited from history, but as a confident nation united by shared values and common purpose.

As Perak ruler Sultan Nazrin Shah observed (The Edge Malaysia, Aug 12, 2024), “Our inclusivity - our celebration of diversity - is absolutely integral to our continued prosperity as a nation. Malaysians of all races, religions, and geographic locations need to believe beyond a shadow of doubt that they have a place under the Malaysian sun.” - Mkini

RANJIT SINGH MALHI is an independent historian who has written 19 books on Malaysian, Asian and world history. He is highly committed to writing an inclusive and truthful history of Malaysia based upon authoritative sources.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.