Sunway Group’s backpedalling on its promise of an animal-friendly mall reveals something deeper than a corporate policy reversal.

It exposes Malaysia’s unresolved discomfort with dogs in public space; a discomfort that is selective, inconsistent, and shaped less by practicality than by anxiety, optics, and unresolved debates around religion and modern urban life.

When dogs are deployed in search-and-rescue operations, we celebrate them. We share viral videos of K9 units pulling survivors from rubble, sniffing out drugs, and locating missing persons. Dogs, in these moments, are heroes: disciplined, loyal, and indispensable.

But place the same animal on a leash in a park, a mall, or a train station, and suddenly it becomes a problem. Complaints surface. Concerns are raised. Management retreats. Policies are “reviewed.”

This contradiction is not accidental. It reflects how Malaysia has chosen to tolerate dogs only when they serve the state or perform a clearly defined function.

A working dog is acceptable. A companion dog, especially one belonging to an ordinary citizen or a blind person, walking calmly beside its human, is not.

I have travelled widely in cities like London and Paris, where dogs are not exceptional presences in public life. They ride trains. They sit under cafe tables. They nap quietly in bookstores and parks.

Not because Europeans are uniquely enlightened or because dogs there are magically better behaved, but because public space is understood as shared space. The assumption is not that a dog is a nuisance, but that it is part of someone’s daily life.

In these cities, the burden is on the owner to be responsible, not on the animal to justify its existence. Leashes, training, and social norms do the work; not blanket bans driven by fear of backlash.

So what, exactly, is the problem in Malaysia?

The usual answer comes quickly: religion. Dogs are considered najis mughallazah in Islam, and therefore their presence in public spaces is said to cause discomfort to Muslim communities.

This concern deserves to be acknowledged, not dismissed. Malaysia is a Muslim-majority country, and public policy cannot ignore religious sensibilities. But acknowledging religious concerns is not the same as allowing them to become a blunt instrument that shuts down discussion.

Islam itself is not monolithic. Across Muslim-majority countries such as Turkey, Morocco, Bosnia, and parts of the Middle East, dogs exist in public life without the level of panic or prohibition we see here.

Jurisprudence varies. Cultural practice varies. But accommodation is possible.

What we are dealing with in Malaysia is not theology alone, but a particular interpretation of religion entangled with social control, moral policing, and an increasing discomfort with ambiguity.

The dog becomes a symbol of westernisation, of liberal values, of boundaries being blurred. It is easier to ban the animal than to have a difficult conversation about pluralism and coexistence.

Sunway’s speedy retreat

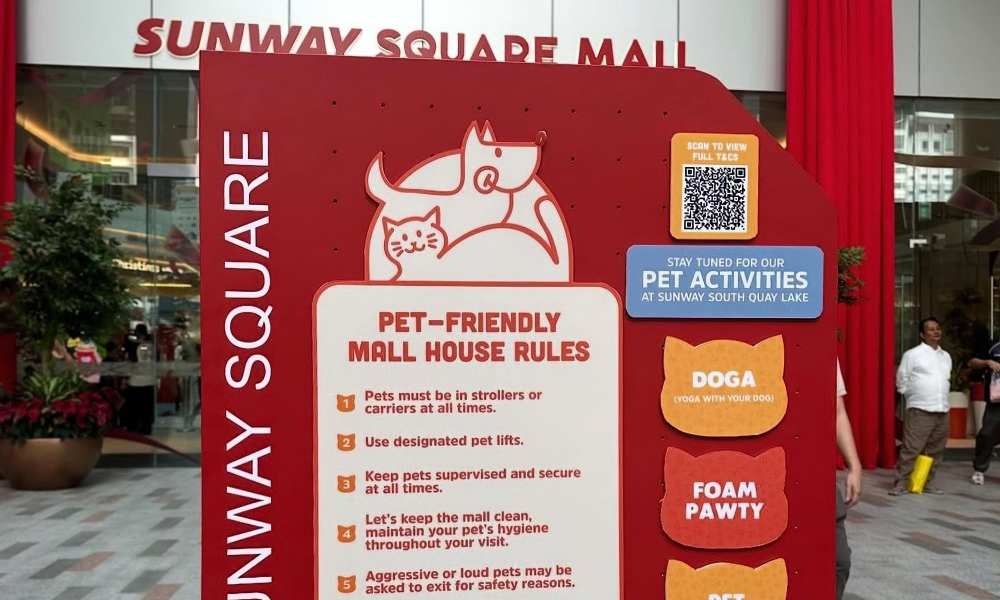

Corporate actors like Sunway Group are especially revealing in this context. When Sunway initially positioned its mall as animal-friendly, it was celebrated as progressive, inclusive, and in step with global urban trends.

When backlash emerged, the retreat was swift. This is not just about dogs. It is about how corporations in Malaysia respond to pressure: not by facilitating dialogue or designing thoughtful compromises, but by pre-emptively surrendering to the loudest objections.

In doing so, they reinforce the idea that public space must always default to the most restrictive interpretation of comfort.

Yet public space, by definition, is shared. It is meant to involve negotiation, tolerance, and a degree of discomfort. Dogs are not uniquely disruptive. A leashed, well-behaved dog poses no greater challenge than many things we already accept as part of urban life.

The refusal to even attempt accommodation is telling. Designated zones, clear signage, education campaigns, leash requirements, and time-based access are all tools used in other cities.

They require effort, yes. They also require trust: in citizens, in dialogue, in the possibility of coexistence.

Only tolerated when useful

Instead, Malaysia defaults to prohibition, and prohibition has consequences. It marginalises pet owners. It isolates people who rely on companion animals for mental health and emotional support.

It sends a message that certain ways of living, often associated with urban, younger, or non-Muslim populations, are perpetually suspect.

It also entrenches a deeply instrumental view of animals. Dogs are valuable when they serve power structures: as police tools, rescue assets, and security equipment.

They are suspect when they serve companionship, care, or joy. This hierarchy mirrors how we often treat people, too: useful bodies are tolerated; autonomous ones are policed.

The irony is that Malaysia prides itself on diversity. We market ourselves as multicultural, hospitable, and globally connected.

But diversity cannot exist only at the level of food and festivals. It must extend to how we design and govern shared space and how we allow different lives to unfold alongside each other without panic.

The question is not whether everyone must like dogs. The question is whether dislike should dictate exclusion. Whether discomfort, rather than harm, becomes the standard by which access is denied.

Sunway’s backpedalling may seem like a small corporate decision. It is not. It reflects a broader unwillingness to imagine public space as flexible, negotiated, and genuinely shared.

Until we move beyond fear-based policymaking, whether driven by religion, politics, or public relations, Malaysia will continue to shrink its commons instead of expanding them.

Dogs in public spaces are not a threat to society. They are a test of it. - Mkini

MAHI RAMAKRISHNAN is a veteran journalist turned rights advocate and consultant, who believes the world is vast enough to accommodate all beings and abhors hypocrisy.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.