On June 27, Emilia Hanafi unwillingly surrendered herself to serve a seven-day prison sentence meted out by the Syariah Court for rescheduling a visitation date for her ex-husband, Naza group chairperson SM Faisal SM Nasimuddin, to see their children.

Criticism of the jail sentence as being excessive caused Petaling Jaya MP Maria Chin Abdullah to be charged with contempt.

The action taken against Emilia and those who spoke out for her has become a symbol for those who believe that this country’s syariah courts systematically discriminate against women.

The syariah courts have purview over Islamic family matters such as divorce and inheritance, as well as ruling on syariah criminal matters - based on Islamic laws which differ from state to state.

Those with unfavourable views of the courts accuse it of silencing women facing injustice, unfair treatment, and excessively prolonging divorce cases, among others.

Pial Khadilla Abdullah, 39, spent seven years trying to finalise her divorce through the syariah courts.

While she accepts that divorces can be simple in the syariah courts through mutual agreement, her experience was rife with what she believed was biasedness at every level.

“When one party refuses or brings up a claim then it becomes complex and herein lies the biases and prejudices.

“These biases and prejudices can start from the bottom - the staff at the counter, employees of the court, lawyers, judges - all the way to the top,” she claimed.

The biases include perceptions of a person’s wealth, religiousness and emotions, added the mother of two.

Pial Khadilla’s experience rings back to the high-profile case of Aida Melly Tan Mutalib, whose divorce was only settled in 2002 after seven years of battling in court.

Aida was unable to divorce her abusive husband as he kept appealing every petition she had filed.

Her case only came to an end after Selangor ruler Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah answered a letter she wrote to him and he advised the court to expedite the decision-making process on her fasakh application.

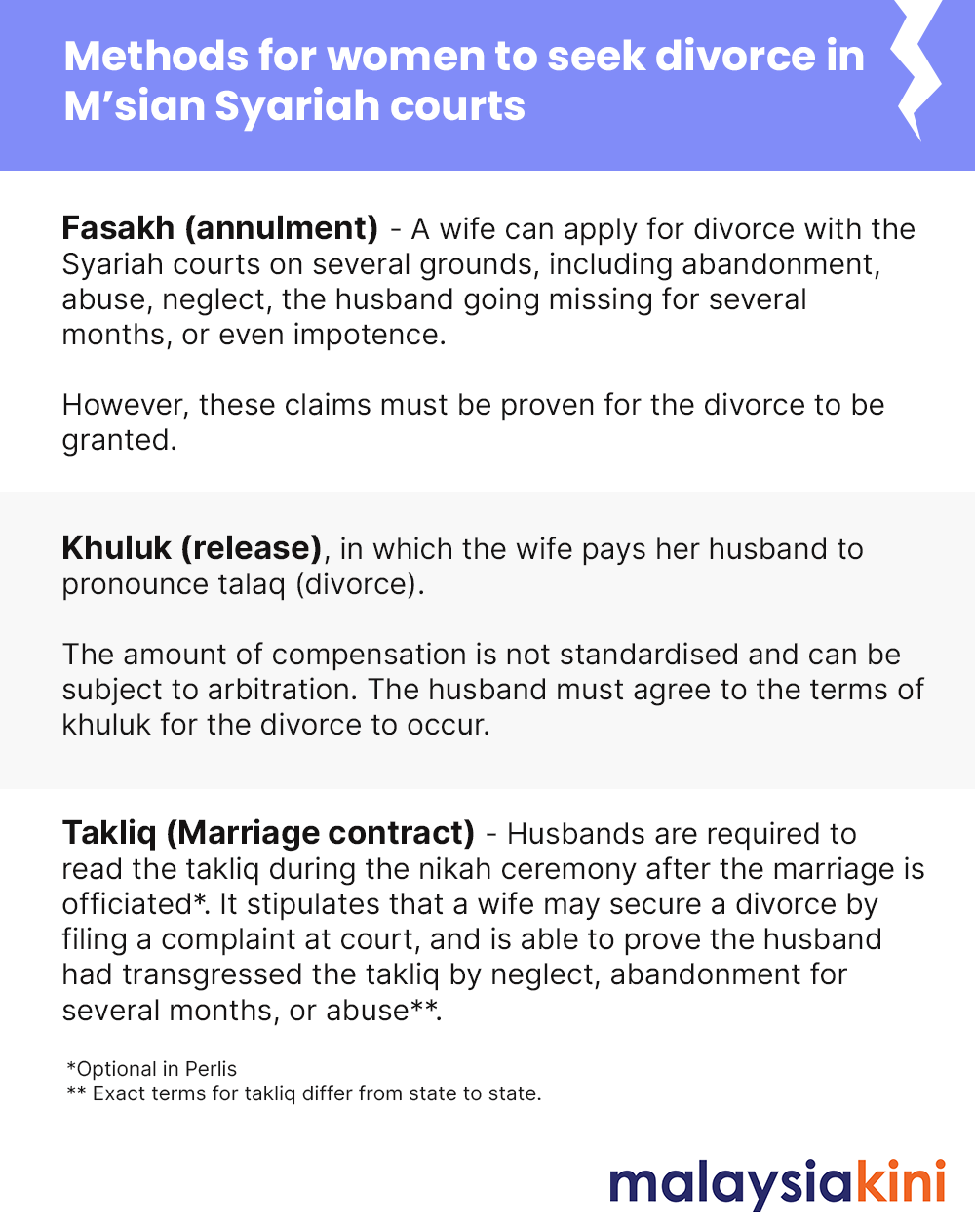

Comparatively, for men, simply saying “I divorce you” while of clear mind is sufficient in theory to end the marriage via talaq.

However, in practice, this must be verified by the syariah courts as well - leading to some cases in which men deny what they have pronounced divorce.

But even seemingly straightforward talaq cases are often dragged out in the country’s Islamic courts, as was experienced by Aliya (not her real name).

Aliya was divorced in 2020. However, the courts delayed hearing the talaq case for six months due to the lockdown - allegedly because it was “not important”.

Worse yet, she claimed the lawyer she sought help from cheated her and billed her every time the court date was postponed.

Her legal fees quickly added up to RM5,000.

Towards the end, she could no longer afford to pay for the lawyer’s services, resulting in her dropping her application for alimony from her ex-husband.

“It is shocking, do they (the courts) know that women are left just like that, stranded without mental support? It is stressful.

“It makes me sad because it is said that Islam always fights for women’s rights, but I do not see that in the country’s Syariah Court system.

“I felt cast aside and stranded,” she told Malaysiakini.

Poor knowledge of Islamic law

Like Aida, Aliya too had to seek intervention in order to get her case heard, this time from her state’s chief syariah judge.

Syariah lawyer Saiyidah Izzati Nur, however, believes negative perceptions towards the syariah legal system are not entirely true and stem from poor knowledge of Islamic law.

“I used to be one of (those) people (who did not know much about syariah law), but after I started practising syariah (law), I learned more about the laws and how it can easily be misjudged as unfair to women specifically.

“In my opinion, the Syariah Court system treats everyone equally, (it) listens and gives opportunities to both men and women to present their cases regardless whatever the grounds or cause of actions are,” she told Malaysiakini.

However, the Shah Alam Muda member acknowledged that the Syariah Court system is slower in comparison to the civil court system and may induce more stress on those who are in the system - regardless of gender.

“You are not going to believe the statistics of abused husbands who filed their application for a separation or divorce in both (syariah and civil) courts throughout (the lockdown) period, it affects both genders.

“The system discriminates against both genders. But yes, it is easy to be biased by saying it affects women worse than men,” she said.

Saiyidah added that she has not witnessed any form of purposeful targeted discrimination during her three years of practice.

Late procedures a form of discrimination

Still, administrative delays and hurdles can be a form of discrimination against the more disenfranchised party in a divorce case, said newly elected PKR Women’s chief Fadhlina Sidek.

Fadhlina, who is also a syariah lawyer, believes that the courts are slowly becoming more progressive but issues such as late procedures, rights of a woman post-divorce, and child maintenance remain unaddressed.

“When talking about discrimination, the process (of court proceedings) is also a form of discrimination. Because a woman leaving a household is then faced with the battle of filing (many) cases.

“For example, if she is a survivor of domestic violence, she has to file for divorce, interim child maintenance, interim custody, custody and an injunction.

“Who has the money to submit five applications if there is no access to justice? There is limited legal aid (for syariah courts),” she said.

Unlike the civil courts which are established by the Federal Constitution, the Syariah Court falls under the jurisdiction of each state.

Inability to navigate court system, afford fees

Further, the Syariah Court system has not gone through a similar digitalisation process as the civil courts in Malaysia, advocacy group Sisters in Islam (SIS) said.

“There are no auditory or video recordings in the court, which may result in discrepancies between the lawyers’ records as well as the courts’,” it said in a statement.

Last year, SIS’s legal aid office Telenisa, which helps women and men navigate the Syariah Court system, served a total of 426 clients, of which 92 percent were women.

A total of 90 percent of SIS clients sought legal advice from the NGO, whereas 5 percent requested legal representation in the Syariah Court.

According to SIS, 56 percent of their clients consisted of support staff and homemakers in the B40 income group.

Like Aliya, SIS noted that their clients find it difficult to afford the legal fees, as the fees are not regulated and are usually too expensive for them.

Due to long waiting lists at legal aid centres or the urgency of cases, most of the clients would often resort to self-representation in the Syariah Court.

“However, this would usually bring our clients to a disadvantage as they are not well-versed or they do not have the experience with court procedures and applicable laws.

“Although access to justice seems apparent, there are still barriers to overcome in ensuring a fair and just legal system,” SIS said.

‘Don’t make prosecuted women beg for sympathy’

Syariah lawyer Nizam Bashir said there appears to be a reticence from the Syariah Court when responding to letters and a slow turnaround time where file searches or court record requests are concerned.

To him, this is contrary to the proper functioning of a court.

“I hear from clients that syariah courts take a long time to deal with their divorce cases, are slow in resolving custody issues, and don't move quick enough or effective enough in issues of maintenance.

“When you hear these things often enough, it's cause for concern. To allay these concerns, perhaps the syariah courts should be more transparent with their data so that relevant stakeholders can be more constructive with their views,” he said.

However, he noted that some states have taken steps to remedy this issue.

“Ultimately, it pays to keep in mind that syariah courts - while deserving of respect - at its simplest provide a ‘service’ to the public and we need to be mature enough to be able to accept criticisms in stride vis-a-vis the delivery of that ‘service’.”

He said it could be as simple as making sure there are more brochures in place to guide single mothers on how to claim child support, and by allowing applications for typical family law claims to be made online.

A good example, he said, was the Singapore Syariah Court where individuals visiting the court website are directed to areas which apply to them instead of having to figure it out on their own as in Malaysia.

After struggling to navigate the court system to finalise her divorce, Aliya feels the Syariah Court urgently needs to be simplified.

She also feels more lawyers should provide pro bono services in the Syariah Court, and for the court to make this service known to those in need.

“Any women, especially single mothers who are abused, cannot afford to pay for the services of lawyers up to thousands of ringgit.

“Don’t make persecuted women beg for sympathy,” she said.

Malaysiakini has contacted the Syariah Judiciary Department and Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Religious Affairs) Idris Ahmad for comments. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.