In July, Malaysia’s Department of Statistics (DoS) released a population estimate report for 2023, sparking social media discussions.

The invention of population data is a legacy of the Enlightenment in 18th Century Europe - a period which brought modernisation and rationalisation to statecraft.

This era also saw the separation of society and the state. The former became an object that could be objectified, simplified, abstracted, engineered, controlled, and transformed.

Population statistics include various demographic characteristics such as gender, health and disease, and education levels. Other areas covered include literacy rates, occupation, life expectancy, labour participation rate, and productivity. Such statistics, which facilitate taxation and social governance, are a tool of modern statecraft.

Malaysia too underwent significant state-building, especially under colonial rule. This included a transformation in governance practices, such as the introduction of population statistics, birth records, and death registrations.

The colonial era saw the introduction of topography. The data provided information on modern facilities like roads and railways. It also showed the distribution of crops and natural resources, such as rubber plantations, forest reserves, minerals, and rivers.

Such data facilitated colonial capitalism’s exploitation of natural resources in the colonies. Similarly, land surveys allowed for the development, distribution, and privatisation of land.

All this, as well as architectural drawings and other technologies, were used to objectify society and the natural environment.

The colonial administrators established the Statistics Bureau, the predecessor of the DoS, after World War Two. Initially, the bureau collected and recorded only trade data in Malaya. Other data was recorded and published by various administrative departments.

After independence, the functions of the Statistics Bureau gradually expanded to include the collection of demographic and economic data.

Such data includes population estimates, age structure, literacy rates, the labour participation rate, the (un)employment rate, wages and the development of various sectors.

Statistics may be useful for research and advocacy, especially in policymaking.

However, many social studies have pointed out that population and other large-scale national data are not neutral tools. This is because statistical techniques themselves embody the perspectives and values of state administrators.

How to define a certain social characteristic and which aspects of things should be measured and recorded - all this constitutes a specific perspective, even though implicit, on how to view society. It is a socially constitutive tool.

The colonial administrators’ population statistics divided the people of Malaya into different ethnic groups, illustrating the colonial construction of race.

Over time, Malaya’s culturally heterogeneous colonial society crystallised into an oversimplified notion of different ethnic groupings, as imposed by the colonisers.

These evolved into predetermined ethnic labels and reduced the population into ethnicised or racialised communities, which we take for granted today.

This racial classification continues to be an essential tool of state administration under the post-colonial ethnocratic regime. Unfortunately, it limits our understanding and imagination of what Malaysian society is.

Pointing out the notion that statistics is not a neutral tool but one that always comes with an implicit perspective is not to oppose the use of statistics but to reflect on how to engage statistics more consciously.

Some policy researchers argue that interpreting population statistics is as socially consequential as population data collection. How statistical data is interpreted and used is itself a form of agenda setting, which constructs a certain perspective of society; hence it is socially consequential.

Not just a numbers game

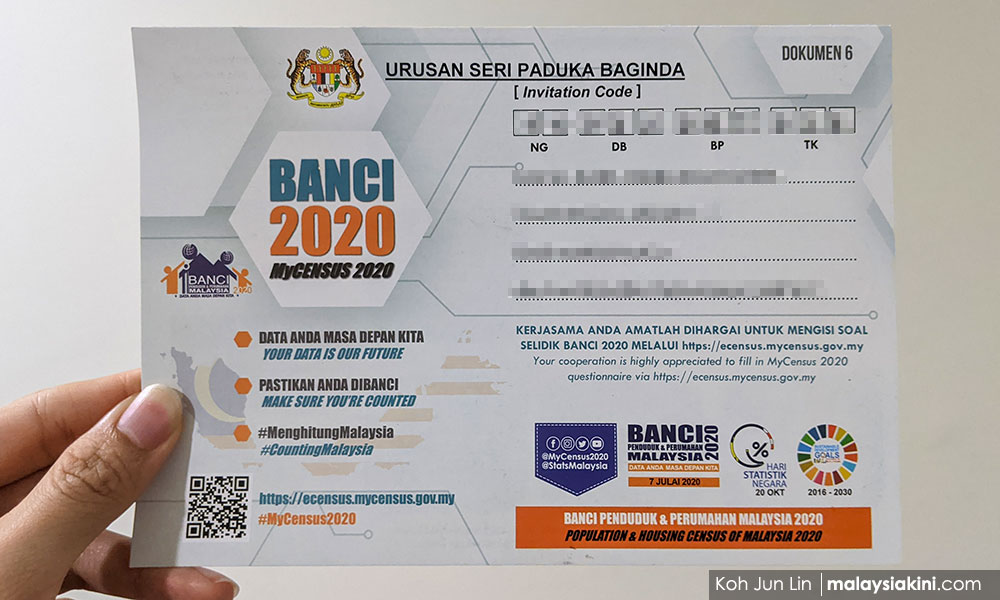

Now let’s turn to the 2023 population statistics mentioned at the beginning.

Some argue that this latest data has a couple of significant implications for the ethnic Chinese community in Malaysia.

First, it reveals a negative growth of the Chinese population for the first time. Second, the population of ethnic Malays in Penang now surpasses that of the Chinese for the first time; the Malays have become the largest ethnic group in the state.

The DoS population statistics follow the colonial classification of ethnic groups as the main social categorisation of the population.

But they also include other social categories, such as gender and age. These categories are very useful for policymakers to estimate age trends in the population. These trends are important for policymaking on welfare for senior citizens and women and on caregiving for older adults in an ageing society.

Unfortunately, those lamenting the negative growth of the Chinese population and how they have been surpassed by other ethnic groups focus solely on the ethnic classification of the people.

They interpret changes in the national demography as indicators of changes in the status, rights, or power of a certain ethnic group.

Such laments completely ignore other more significant messages and information in the population statistics. They reflect the commenters’ preference for a narrow racial perspective or their lack of appreciation for the functions of statistics.

Interpreting population data this way reinforces the narrow racial perspective and racial politics imposed by the ethnocratic authoritarian regime. It also reveals the commenters’ refusal to see democratic politics as a multi-layered process of negotiations and struggles.

These commenters see the population numbers as key to safeguarding minority rights. They appear anxious about the drop in the ethnic Chinese population, but they are actually envying the dominance of the majority ethnic group.

They have also made a factual error. The number of Malays in Penang has long surpassed that of the Chinese, since as early as 2013, instead of in 2022.

Anxious patriarchal desires

A strong sense of racial anxiety may offer no insights in countering racial politics in the country. It is but a continuity of the past rhetoric by many Chinese organisations, which encouraged the Chinese community to “make more children to safeguard the rights of the community”.

Such rhetoric reflects the unspoken instrumental assumptions about women’s bodies and reproduction. It takes for granted the sacrifices of individuals for the collective interests of the ethnic community.

An oversimplified notion of democratic politics often views it as just a game of numbers. Such a notion ignores the fact that population changes involve long-term social transformations.

Democratisation is a process that involves both short and long-term struggles. It involves the rights of ethnic minorities and even the rights of individuals. It cannot be understood as a “birth rate” competition.

Calling for more births is but an act of self-consolation. The “make more babies” slogan is but community-led social engineering premised on patriarchal assumptions. Such concerns are a manifestation of intellectual poverty among those commenters who came up with such a narrative.

Ageing communities

So, what is the important message of the latest population statistics?

According to the DoS open database, people aged 65 and above made up 7.4 percent of the population at the end of 2022. Compared to the global average of 9 percent in 2019, Malaysia’s population is considered young.

However, inspecting the demographic differences between ethnic groups, the proportions of people aged 65 and above among the ethnic Malays, Chinese, and Indians are 7 percent, 10 percent and 8.1 percent respectively. So the ageing trend is most serious among the Chinese.

But ageing itself does not imply disability and should not be discriminated against or be automatically considered a “social problem”. Specialised care is needed only for older individuals who lack the ability to care for themselves.

Declining birth rates and the migration of younger generations complicate the long-term care issue for disabled elderly members of the Chinese community even more.

This issue, rather than “the number of ethnic Chinese is lower than a certain ethnic group”, is the real and urgent issue that requires attention.

The current market price for long-term care services for the elderly ranges from RM2,500 to RM8,000 per month, depending on the degree of disability, the facilities, and the level of comfort of the nursing home.

Well-off families can afford to hire caregivers at home or send older family members who cannot take care of themselves to nursing homes.

However, middle and low-income households cannot afford this. The responsibility of caregiving often falls on family members - the spouse, unmarried children, or more marginalised family members.

Without policy intervention by the state or collective efforts from the community, families with disabled elderly members will face multiple challenges alone.

In several more developed Asian nations, reports have surfaced of family members who are caregivers ending the lives of those they care for due to isolation and unbearable mental pressure.

In Japan, “kaigo rishoku” refers to the situation where an individual leaves the job market to care for an elderly family member - a situation which often ends in deep poverty for both the caregiver and the care recipient.

All this is due to the lack of social and institutional support.

State intervention is needed not only to provide financial support and affordable care. It is also needed to provide professional training to caregivers and to ensure an adequate supply of professional elderly care workers and fair remuneration for them, many of whom are women.

Apart from relying on the state, it is also important to create a sustainable and self-sufficient community elderly care system.

A smaller population should not be a concern for the Chinese community. A lack of sociological reflection on population statistics and a lack of perspectives beyond the ethnic lens are more significant problems.

Yes, statistics is a tool of statecraft which aims to engineer, transform and control society and the population from the top down. But it can also be an important tool for civil society to monitor government performance from the bottom up and press for reforms.

This way, we can collectively build a welfare state and a caring society that provides for the care of vulnerable groups. - Mkini

POR HEONG HONG, an Aliran executive committee member, is a social scientist by training. This article was first published in Aliran.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.