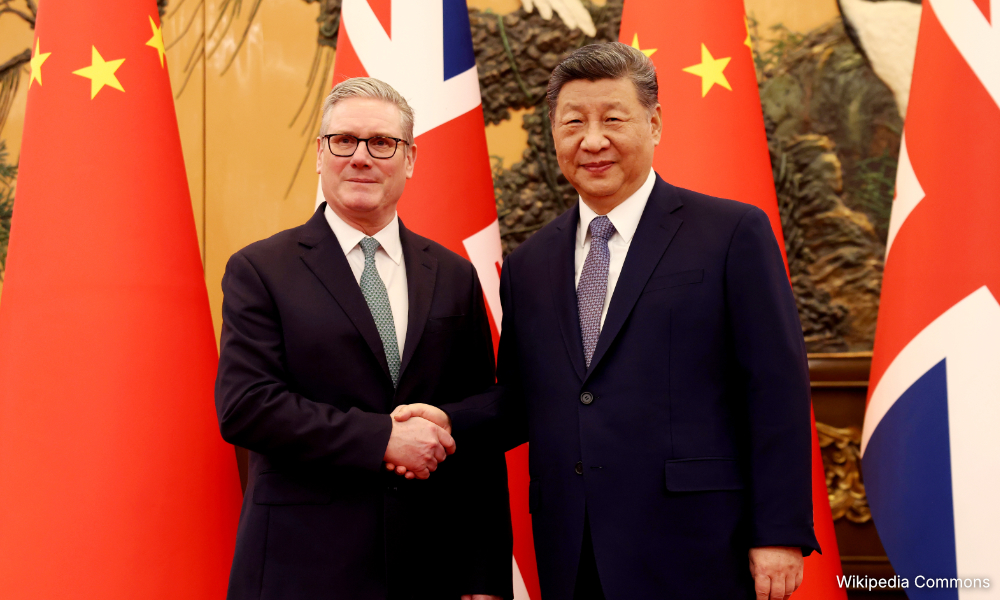

The United Kingdom’s recent reset in relations with China marks a significant recalibration of British foreign policy, one that extends beyond bilateral diplomacy and reshapes the wider architecture of the UK’s engagement in Asia.

After years of strained ties characterised by security concerns, human rights disputes, and political distrust, London has signalled a pragmatic turn toward economic cooperation and structured dialogue with Beijing.

This shift reflects economic necessity as much as strategic calculation.

Facing sluggish domestic growth, post-Brexit trade pressures, and global uncertainty, the UK is seeking renewed access to Chinese markets in trade, services, finance, and green technology.

Yet this recalibration is not simply about restoring commercial flows; it also represents a repositioning of Britain’s global identity as it attempts to balance economic engagement with strategic caution.

In this evolving context, Malaysia emerges as an important secondary actor whose bilateral relationship with the UK may be subtly but significantly reconfigured by the UK–China reset.

At its core, the reset signals a move from ideological confrontation to managed competition. The UK government has emphasised the need for a “sophisticated” relationship with China; one that protects national security while advancing economic interests.

This balancing act mirrors broader European trends, where governments increasingly pursue “de-risking” rather than decoupling from China.

For Britain, the logic is clear: China remains one of the world’s largest economies and a key player in global supply chains, climate negotiations, and technological development.

Total disengagement would be economically costly and diplomatically isolating. However, re-engagement carries reputational and strategic risks, particularly in relation to allies who remain wary of Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions.

This duality: engagement without endorsement defines the complexity of the reset and frames its downstream implications for Southeast Asia.

Strategic middle ground

Malaysia, with its long-standing ties to both the UK and China, occupies a strategic middle ground in this recalibrated landscape.

Historically linked to Britain through colonial legacies, educational networks, legal traditions, and defence arrangements, Malaysia also maintains deep economic integration with China, which is its largest trading partner.

Kuala Lumpur’s foreign policy tradition emphasises non-alignment, pragmatic multilateralism, and diversification of partnerships. In many ways, Malaysia has already been practising the kind of balancing act that the UK now seeks to adopt.

As Britain reopens channels with Beijing, it may find in Malaysia a partner that understands the intricacies of navigating great-power competition without formal alignment.

Economically, the reset could generate indirect benefits for Malaysia-UK relations. A more commercially confident UK presence in China may encourage British firms to adopt a broader regional strategy across Asia, using Asean states such as Malaysia as complementary hubs for manufacturing, services, and digital innovation.

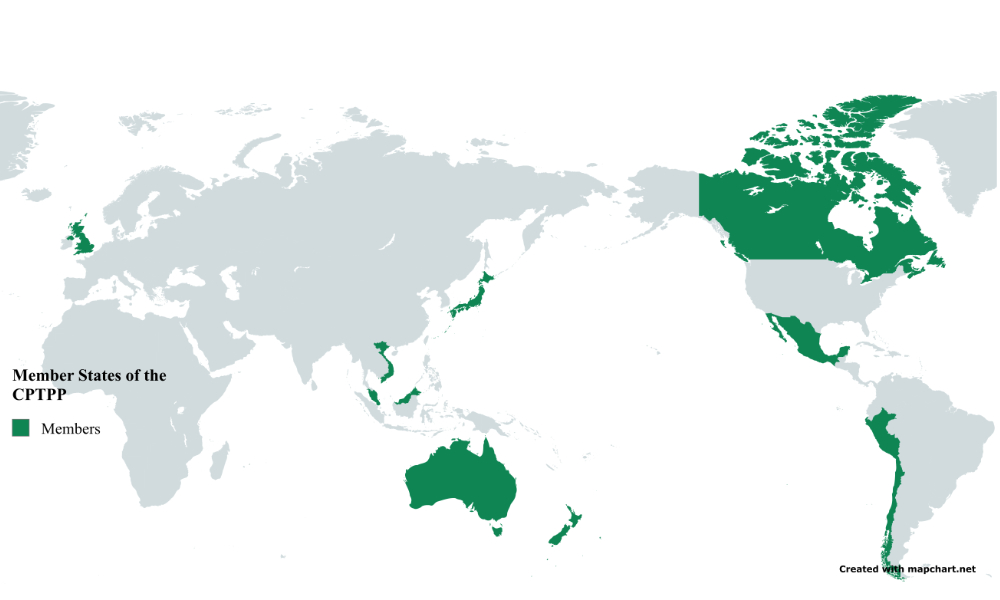

Malaysia’s membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), now joined by the UK, strengthens institutional linkages and provides a multilateral framework for expanding bilateral trade.

Rather than viewing China and Asean as competing arenas, Britain may increasingly treat them as interconnected components of its Indo-Pacific economic strategy.

Malaysia could therefore serve as a stabilising platform for UK investment diversification, especially in sectors such as renewable energy, Islamic finance, higher education, and advanced manufacturing.

Beyond economics

However, the reconfiguration is not purely economic. Strategic signalling also matters. The UK has sought to maintain an Indo-Pacific tilt, reinforcing defence dialogues and participating in regional forums to demonstrate continued commitment to maritime security and rules-based order.

A warmer relationship with China might raise questions among regional partners about the consistency of British commitments.

For Malaysia, this creates both opportunity and caution. On one hand, a UK less overtly confrontational toward China may be seen as a constructive interlocutor capable of engaging multiple sides.

On the other hand, Malaysia must ensure that closer UK-China ties do not dilute Britain’s support for Asean centrality or undermine collaborative approaches to South China Sea tensions.

The recalibration thus requires diplomatic finesse on both sides to prevent misperceptions.

Critically, the reset also exposes structural limits. Economic cooperation with China may improve trade flows, but it does not erase systemic competition in technology, security, and governance models.

The UK’s desire to attract Chinese investment while safeguarding critical infrastructure will inevitably produce regulatory tensions.

Malaysia, which has faced similar dilemmas in managing Chinese infrastructure projects and foreign investment, may interpret Britain’s experience as validation of its own cautious pragmatism.

In this sense, the reset does not radically transform Malaysia-UK relations; rather, it creates space for deeper dialogue on managing strategic risk in an era of interdependence.

Ensuring Asean’s interests

Another dimension concerns diplomatic bandwidth. As Britain invests political capital in stabilising ties with Beijing, there is a possibility that Southeast Asian concerns receive comparatively less attention.

Malaysia may need to actively engage the UK to ensure that Asean priorities: economic integration, digital transition, climate resilience remain visible within British policy frameworks.

Yet this challenge also presents opportunity: by positioning itself as a reliable, moderate partner, Malaysia can shape how the UK conceptualises its broader Asian engagement beyond China.

Ultimately, the UK-China reset does not represent a dramatic pivot away from existing partnerships but rather a recalibration within them. For Malaysia, the implications are evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

The reset encourages a triangular dynamic in which Malaysia leverages its balanced diplomacy to strengthen bilateral ties with Britain while maintaining robust engagement with China.

If managed carefully, this configuration can enhance economic diversification, reinforce multilateral cooperation, and sustain regional stability. If mishandled, it could create ambiguity about strategic commitments and dilute mutual trust.

The future of Malaysia-UK relations, therefore, will depend less on the symbolic warmth of UK-China diplomacy and more on the practical ability of both London and Kuala Lumpur to align economic ambition with geopolitical prudence in a complex and shifting Indo-Pacific order. - Mkini

R PANEIR SELVAM is the principal consultant of Arunachala Research and Consultancy Sdn Bhd, a think tank specialising in strategic national and geopolitical matters.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.