The campaign for the state polls is in full swing; walkabouts, ceramah, debates, streams of WhatsApp messages and new TikTok videos galore.

Despite the activity, in this mega state elections, politicians are finding the electorate more disengaged and discerning. In fact, the words being used to describe the hustings are “cool” and “cold”.

Trust in politicians has seriously eroded in the past few years, from former prime ministers Najib Abdul Razak and Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Muhyiddin Yassin to current deputy prime minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, large sections of the population don’t trust any of them, with others only trusting one or two of them.

The betrayal of the Sheraton Move of 2020 still lingers in the minds of many voters, especially in urban areas.

Perhaps with the exceptions of caretaker Kedah menteri besar Muhammad Sanusi Md Nor and Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s loyalists who put their faith in him, the days of political heroes are ending.

Push and pull of Anwar

The campaign in these polls reflects the ongoing changes taking place in Malaysian elections. I highlight these related to the campaign in my ninth piece on the mega state polls.

The first transformation involves the views of the prime minister. Usually early on in a term, Malaysia’s prime minister is given a voter boost, a sweet reception from the electorate as part of a political honeymoon of new leadership.

This appears not to be the case in these state polls to the degree it has been in the past. Anwar has been receiving different reactions on the ground.

In some places, such as Penang and to a lesser degree, Selangor, he is a pull for voters, but in other places such as Negeri Sembilan, Kedah, Terengganu, and Kelantan there has been a push factor.

The polarisation of the electorate feeds into different views of the prime minister.

It is not uncommon to centre a state election campaign around the national leadership - Muhyiddin did this in Sabah 2020, for example. Yet, what is happening this time is that the push away from Anwar is stronger in some states than the pull factor, tipping the balance in some highly competitive seats.

More generally, centring the state campaigns around the prime minister so emphatically has risen the stakes for Anwar’s government in the outcome. This feeds into making these state polls more significant for the future of national politics.

Defensive posture

A second ongoing change is in campaign messaging. What is striking in this campaign compared to those since 1999 has been the largely missing discussion of reform on the part of Pakatan Harapan.

While there are broad calls by Anwar that corruption will be addressed, this promise does not sit well when one of his deputies is facing multiple serious corruption charges. The Zahid factor remains salient for many voters.

Generally, Harapan’s campaign has been on the defensive, centred on defending themselves in power as the incumbents in key states and at the federal level (with Umno). There is a lack of consistent and clear messaging.

Voters are finding it hard to connect to an unfocused stream of announcements, even if some of these offer promise investments and lay out policy directions, as did Anwar’s late-announced economic programme.

As such, Harapan’s campaign so far has largely resonated only with its base, rather than extended its reach to undecided voters and those who voted for Perikatan Nasional (PN).

Unlike previous BN campaigns that had a clear theme and integrated the theme into its strategies, Harapan’s campaign as the federal incumbent is more ad hoc and its messaging is not well-integrated into the campaigns of individual states, including those where it is the incumbent.

Harapan is simultaneously facing challenges holding onto some of its base over its yet unfulfilled promises.

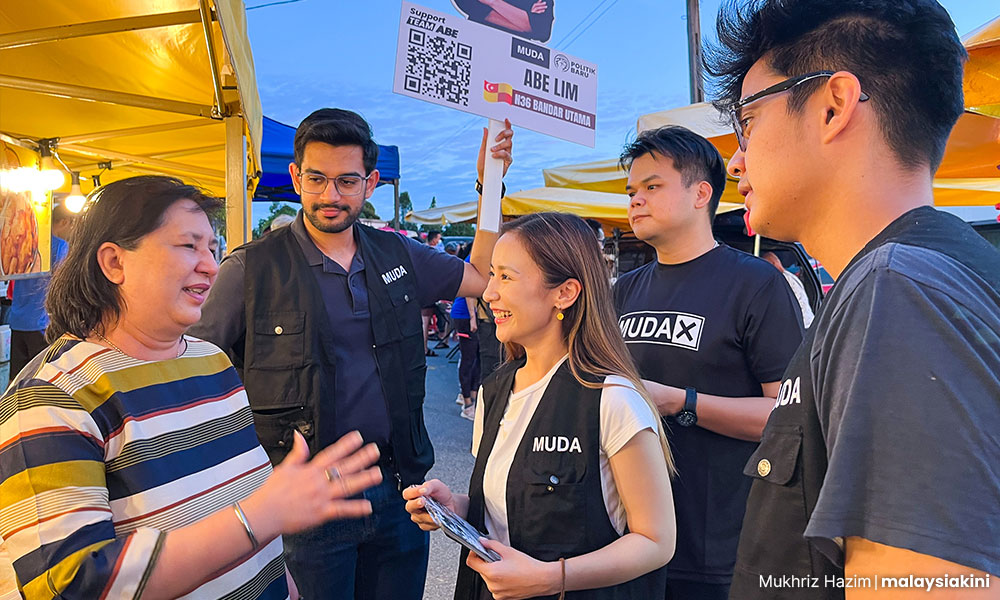

Muda’s campaign message has aimed to tap into these sentiments, to focus on reform and reach out to the young, to capture some of those wanting to maintain attention to strengthening governance and inclusion.

Muda faces a difficult time, in part because Harapan has focused its energy on deflecting this challenge to its core support rather than focusing on the rising power of PN.

Another area where Harapan faces problems is among non-Malays, especially Indians. Many non-Malay voters are less enthusiastic in these elections than in GE15.

There is a sense that they have been ignored by the Anwar government, and some perceive a lack of respect for the struggles minorities experience.

The prime minister’s response to a young Indian girl asking about quota systems in education does little to counter these sentiments.

It remains unclear if and how much these sentiments will translate into changes in turnout and support.

Umno’s lack of messaging

At the same time, Umno, a partner in the federal coalition government, has not promoted a substantive campaign narrative at all.

While party workers still loyal to the party are campaigning hard, they are finding more rejection and silence than before. A distancing from the party continues, especially in places where openly Zahid-favoured candidates have been fielded.

What has not happened to date is the articulation of a convincing narrative to the Umno grassroots on why they should be part of the coalition government.

Also, unlike in previous elections such as Malacca and Johor where Umno’s shared interest in “survival” has dampened infighting, differences persist on the ground as the focus is on individual survival.

The effect is that political support is eroding. While the parties in the coalition are cooperating more than they ever imagined, the campaign to date is not only defensive but disjointed.

Offensive messaging

On the other side, the opposition PN - as oppositions do - have continued to be on the offensive.

While they have lost the complete dominance of the campaign narrative they had at the start of the official campaign period, their messaging is more consistent and on the offensive.

PN continues to channel discontent, appealing to emotions; anger and resentment are mixed with a dose of fear and disappointment.

The offensive racialised dimensions of PN’s campaign are more muted compared to GE15, except in incidents like those in the treatment of the Gerakan candidate in Bayan Lepas in Penang.

Yet the core messages of neo-Malay nationalism tied to both race and religion are connecting with a growing base.

PN’s campaign is reaching out beyond its traditional supporters. What has happened is that the opposition coalition has pivoted its campaign to focus more on concerns with the economy.

This time around they are not in the federal government so they can target Anwar’s administration, which they are doing quite effectively with simple price-focused messaging aka Harapan in the 2013 GE.

PN has a clear goal to change political power. It is promising its supporters they will be able to change the federal government and the governments of Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Penang, promises that are capturing the attention of those wanting change.

The delivery of these promises will come with costs; a change in government in any of these states will trigger greater political uncertainty in these states and nationally.

There is stark irony between the PN posters professing stability, with messages and campaign aims that will increase political instability.

For many urban voters, the PN campaign about changing power triggers reminders of the Sheraton Move, seen to destroy their hopes for change.

PN is still comprised of the same leaders who were involved in this takeover, and those who felt betrayed are still angry.

Winning power in these three West Coast states remains highly challenging, although not impossible, notably in Selangor. PN’s base is growing, but unevenly across different seats and states.

Comparatively, their campaign began earlier, is more organised, and appears to have more resources than that of the federal coalition government, yet they also have the baggage of the past that voters remember.

Evolving political engagement

Besides messaging, the way in which the message is being delivered is changing. Ceramah are not receiving the same level of attention and participation. More of the campaign messaging is being delivered through smartphones via chat messages and social media, especially TikTok.

PN continues to dominate the algorithms in TikTok, with its candidates having more followers and its messages gaining more traction. Nine months after GE15, the unity government wrestles with making its presence felt on the social media platform popular among youths.

While there is clearly more of a presence than before, Harapan is still trailing in connecting with voters in the medium, especially among undecided and younger voters.

Campaign machineries are also weaker compared to the past, as the six elections are stretching the capacity of all the parties who have fewer volunteers enthusiastic about the campaign. Noticeably, so far, the campaigns lack the flush of cash of the past.

As such, the effect is that there is little new for voters to embrace from the main coalitions, to attach hope to. In many ways, the state election campaigns are an epilogue of GE15, a remake with less excitement and less engagement.

Yet, as Malaysian election campaigns become more ordinary and less extraordinary, the possibility of political change persists. “Just ordinary” elections are now increasingly a part of Malaysia’s democratic fabric, with political turnover also becoming more normal as well.

There is still a week to go before the state elections and campaigns in Malaysia do matter as many who disengage are only now turning back into political issues.

Given the number of highly competitive seats, the week ahead will be critical in determining not only the scope of political turnover but the direction of the country.- Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honourary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute. She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.