Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Malaysia on April 15 was received with great pomp by the government.

Even before his arrival, state-owned broadcasters (Bernama TV, TV AlHijrah) and private media (8TV, Coolita smart TV platform) were already mobilised to air China Media Group's (CMG) grand external propaganda programmes.

When Xi arrived, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim welcomed him at the airport - an unmistakable display of sycophantic eagerness from the government.

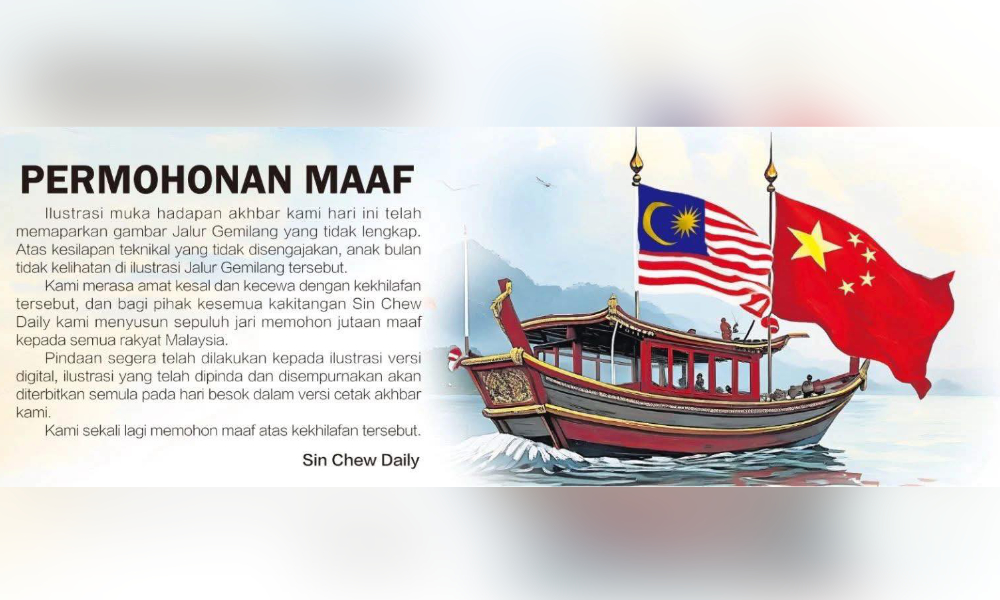

Ironically, on the very day of Xi’s arrival, Sin Chew Daily published a front-page advertisement promoting an article bearing Xi’s byline - yet the accompanying image contained a glaring error: the crescent on the Malaysian national flag was missing.

This sparked public outrage, especially within the Malay community. Even a former education minister in the Pakatan Harapan government, Maszlee Malik, lambasted the daily, stating that the flag symbolises national sovereignty (kedaulatan) and that someone must be held accountable - either by resigning or facing legal consequences.

On social media, numerous Chinese netizens also criticised Sin Chew Daily, with some even echoing calls for legal action.

The incident quickly escalated. The Home Ministry, the Communications Ministry, and the police launched investigations. The police detained Sin Chew Daily's editor-in-chief and deputy chief sub-editor after the gaffe.

Sin Chew Daily also suspended the duo pending the outcome of the investigation. It was reported that the Home Ministry and the MCMC also investigated Penang-based Kwong Wah Yit Poh for publishing a photo of a Malaysian flag with an incomplete crescent.

Sin Chew Daily indeed committed a technical mistake by failing to properly vet the image before publication. Whether the mistake was caused by the use of artificial intelligence (AI) (which is highly likely) or due to the tight turnaround times typical of the newsroom is not the crux of the issue.

Rule of law

What truly warrants reflection is this: Why is it that in this country - whether the government or the public - there is always a tendency to respond to mistakes from media (or other societal institutions) with heavy-handed measures, invoking loaded words like “punish”, “legal actions”, or “heads must roll”?

The concept of the “rule of law” asserts that all are equal before the law, and no one, regardless of status or power, is above it. This is fundamentally different from “rule by law” - where those in power wield the law as a weapon to control others. Demanding punishment for every media mistake reflects a conflation of these two principles.

In this incident, the claim that a missing crescent harms national sovereignty (kedaulatan) may sound grave, and many have supported the government’s enforcement actions. Yet, such claims of “national sovereignty” or the oft-used phrase “hurting the feelings of a nation’s people” are official rhetoric aimed at justifying state actions (or inactions) as legitimate.

Non-intentional actions involving the national flag - such as displaying it upside down or omitting elements - do not, in reality, pose any clear and present danger to national sovereignty.

But such rhetoric is consistent with how successive Malaysian governments - be it BN, Perikatan Nasional, or Harapan - have long used terms like “racial harmony”, “social order”, and “national security” to justify crackdowns on freedoms of assembly, speech, and the press.

The real damage caused by the Home Ministry, Communications Ministry, and police launching investigations over a technical mistake lies in its chilling effect on the media industry, and more broadly, Malaysia’s democratisation.

It sets an unrealistic and punitive standard - that the media must operate with “zero error”.

“Zero error” could be an aspirational goal for media companies to maintain professional standards, integrity, and public trust. It is reasonable, even necessary, for society to hold media to high standards through oversight, critique, and feedback.

However, we must also realise this reality: expecting “zero error” from the media is as unrealistic as expecting “zero crime” in society. When evaluating media mistakes, it is crucial to consider not just whether they pose a clear and present danger, but whether they were intentional.

‘Zero error’

Recognising this, it is dangerous to expect “zero error” to be a legal obligation imposed on the press. Otherwise, the media and journalists would be walking on eggshells - constantly fearing missteps, making it harder for them to perform professionally and courageously.

If those calling for Sin Chew Daily to be punished are assuming or accusing the paper of deliberately omitting the crescent, two possibilities emerge:

(1) Ignorance. Malaysian media have long operated under the “Sword of Damocles” of draconian media laws. Traditional media, wary of having their publication permits or broadcasting licences revoked, have historically complied strictly with government demands.

In fact, Sin Chew Daily had its publication permit suspended during the 1987 Operasi Lalang. Since then, it has treaded carefully.

The notion that it would deliberately omit the crescent to “sabotage” the government vastly overestimates its audacity. On the contrary, the paper’s extensive coverage of Xi’s visit reflects its alignment with the government’s pro-China stance.

In Malaysia, only media backed by powerful ruling parties have the boldness to run racially provocative headlines like “Apa Lagi Cina Mahu? (What more do Chinese want?)” after the general election.

(2) Exploiting a racial political agenda. If anyone is trying to frame this mistake as a Chinese-language media (or Chinese community) act of “loyalty” to China, they are playing an old, dangerous game. The narrative questioning the Chinese Malaysians’ loyalty to Malaysia - a relic from the 1980s - continues to be revived today.

The government bears some responsibility for this, as it has consistently caved in to, or echoed, racial provocations. When ethno-religious provocateurs hype up controversy over A, the government goes after the A - emboldening such actors and encouraging more race-based agitation.

The missing crescent incident serves as a rude awakening: there exists a swathe of citizens who, like the government, subscribe to a rule-by-law mindset. It is precisely because of this that Malaysians are fated to endure democracy’s slow crawl, and continue living with crippled freedoms of expression, press, and media independence. - Mkini

CHANG TECK PENG is an associate professor at the Faculty of Communication and Creative Industries, Tunku Abdul Rahman University of Management and Technology, and leads the university’s Doctor of Philosophy in Communication and Master of Arts in Communication programmes.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.