“Nothing is certain, except death and taxes,” said Benjamin Franklin in 1789, keenly aware that throughout history, tax money has always flowed from the people to the government.

Later still, death and taxes were treated as bedfellows and the deceased were taxed through estate duties aka inheritance taxes. How clever was that to outwit Old Ben and tax us beyond death!

For centuries, tax collected in cash or in kind from farmers, traders, landowners, wealthy individuals, and the dead have funded the machinery of government and civil institutions, wars and national armies and navies, the building of public projects, roads, railways, canals, grand palaces, museums, and hospitals.

In short, “Taxation is the price we pay for civilisation.” (Oliver Wendell Holmes, US Supreme Court judge, 1902-1932)

Then, in May 2008, to spur an economy showing dangerous signs of lethargy if not collapse, the Internal Revenue Service, the American relative of our Inland Revenue Board was directed to send tax rebate cheques of US$600 to most individuals and US$1,200 to couples, equivalent to one percent of the US GDP. The flow of tax money had been reversed!

Yes, in the past, there were food stamps, soup kitchens, and handouts in many parts of the world including wealthy countries. But a tax rebate cheque in the mailbox is like returning to farmers a portion of grain collected from them as taxes. Surely something is not right here? Quantitative easing was around the corner and coming!

The world was flooded with money, making the taxman look more like Santa and less like Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-83) who famously said: “The art of taxation consists in plucking the goose to obtain the largest number of feathers with the smallest possible amount of hissing”. So much for the goose that laid the golden eggs or its liver that became foie gras.

A lesson from history

But let’s be clear on this: e-Madani is neither a tax rebate for the middle class or a food stamp for the poor. It is too small to be meaningful and too restrictive to be a gift. It is at best a gesture and a token that, despite some grumblings and glitches, is still popularly viewed as “free money”. Its effect will not be lasting and will soon be forgotten like any non-event.

Although e-Madani has put a paltry RM100 directly into the pockets and e-wallets of some 10 million citizens, it is a far better thing to do than allowing billions to disappear into the pockets of crooked government contractors, and unscrupulous politicians, experts in padding the costs of government tenders for the supply of warplanes and widgets, or ghost ships.

While e-Madani reverses the flow of money from the government to the people, it is a mere trickle. No one should be fooled into thinking a new age of tax equity and transparency is at hand.

Recent high-profile tax cases, some linked to 1MDB, are clear proof that something is rotten about the state of taxation in our country. The tax net is surely tattered and torn.

Malaysians have always suspected a nexus between the well-connected and the well-greased. So, let’s start with some history. Personal income tax in Penang, Malacca, Singapore (the Straits Settlements), and the Malay States was only imposed in 1948 via Income Tax Ordinance No.48.

Previously, the Malay States and the Straits Settlements imposed their own levies to raise money. In the straits, the authorities relied on excise imposed on “vices and pleasures” through revenue farming of the trade in opium and liquor, prostitution, and gambling.

When properly organised, it made fortunes for the owners of these “farms” and typically they obtained it through their political or royal connections. Stamp duties, introduced in 1863 were abolished in 1867.

In the Malay States, both Federated and Unfederated, revenue was raised through port charges and river tolls and some desultory customs and excise duties. However, the bulk of revenue came from export duties on rubber and tin and import duties on opium.

The taxing of spirits, gambling, and pawn shops was also prevalent in the Federated Malay States and the straits.

Great fortunes in tin and rubber were made prior to 1948 and towns like Ipoh boasted more Rolls-Royces than any other town in Asia. We were rich enough to donate a whole modern battleship, HMS Malaya, which incidentally whisked off the last Ottoman Caliph into exile in Malta even as men and women toiled in rubber estates, tin mines, roads, and railway projects.

Meanwhile, a burgeoning class of professionals - doctors, lawyers, accountants - and merchants were literally minting money. Not to forget high net-worth hereditary chiefs with close ties to wealthy merchants and colonial big shorts.

Yes, these are the Najib Abdul Razaks and Low Taek Jhos of the yesteryears! Yet, no one was paying any income tax as yet. Not a cent. Why?

The main reason: The British colonial administration was custodial in nature rather than developmental. Its main function was maintaining law and order and the promotion of trade and commerce. In other words, maintaining macroeconomic stability, enough to generate operating revenue and the repatriation of profits from rubber and tin.

The lesser reasons: hostile opposition from the European, Chinese, and Indian mercantile and professional communities. Their reasons for pushback: no taxation without representation; expected evasion on a large scale, thus being unfair to those who pay; the tin and rubber industry was struggling and lastly, administrative extravagance using taxpayer money.

Sounds familiar? And here perhaps is the root of poor race relations. Sadly.

That’s history, but the present is not far different. As a gesture, e-Madani is fine but the 10 million recipients of this gift should insist that the tax net must be repaired and put to good use catching tax dodgers, whether VIP or otherwise.

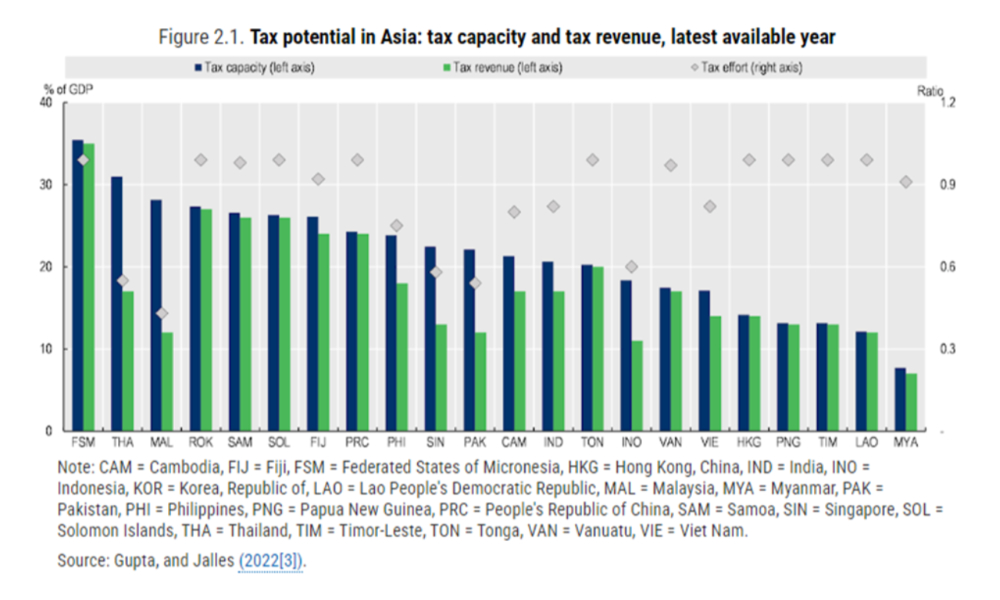

There are research papers that clearly show that our country is still a laggard when it comes to maximising tax revenues. Here is a picture that says a thousand words:

Three terms are key to understanding why we are laggards: 1) tax capacity - which is the theoretical maximum tax revenues an economy can mobilise; 2) the self-explanatory actual tax collection; and 3) tax effort - which indicates what has gone into narrowing the gap between the first two.

Based on the data, we look downright woeful. Like Pakistan and Thailand. Like a country dependent on agriculture, which we are not.

Lack of faith in the system

So, why do taxpayers avoid paying taxes? The long and short of it: a lack of tax equity or fairness; lack of transparency in the use of tax money; spending policies including government profligacy and frightening levels of corruption. All these make taxpayers have little faith in the future of the country. Not the right thing to do but it happens if you are selfish.

True or false, who among us has not heard that every tenth invoice in the building industry is cooked up or that many VIPs get away scot-free and that some even have the temerity to suggest only the weak, the unconnected, and those with payslips pay their taxes! By the way, VIP is now an abbreviation of Very Important Politician.

Who among us can deny that in private conversations we are convinced 1MDB is the tip of the iceberg? Or deny that we share the belief there are many other “undisclosed, deliberately hushed up and not properly investigated” cases of the national coffers being looted? Or that it is in the DNA of certain political parties to treat themselves to taxpayer monies as of right?

The best legacy this Madani Government can bequeath to future generations is to fix the Malaysian income tax system once and for all. Drastic and dramatic action must be taken.

E-Invoicing is one such action. We need more! Go after the big fish, not the small. Only then can we move forward and claim our proper place in this world. Before it’s all too late. - Mkini

MURALE PILLAI is a former planter and now runs a logistics firm.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.