In Malaysia, the climate’s ebb and flow are choreographed by the Southwest and Northeast Monsoons.

From late May to September, the Southwest Monsoon ushers in drier conditions, while the Northeast Monsoon, prevailing from November to March, brings heavy rainfall - impacting regions such as the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia and parts of Sarawak and Sabah.

This climatic ballet, however, encounters unpredictable partners: El Niño and La Niña. These weather phenomena introduce an element of uncertainty to the rhythm, disrupting the delicate balance between seasons.

On the peninsula’s west coast, these uncertainties amplify the challenges posed by climate change, which are acutely observed by farmers, making the pursuit of food security more difficult.

Karisnasamy Thevarayan, 66, a vegetable farmer who cultivates loofah and cucumbers along the Klang River in Kota Kemuning, Selangor, faced the brunt of this during the 2021 West Peninsular Malaysia floods.

Vegetable farmer Karisnasamy Thevarayan working in the farm to plant seedlings on Nov 16, 2023. The photo on the next slide depicts the farm's condition after being hit by a flood on Dec 12.

Faced with the constant threat of floods and decreasing soil fertility, he employed an innovative way of farming called the hanging plant method. Despite this, the floodwaters still reached the bags where his plants grow.

“When the water rises about six feet, the flood automatically damages the lightweight coconut husk inside the polybags (where the plants are grown). Then the water recedes and the polybags are washed away.

“Indeed, it is sad. What can we do? This is not in our hands. It’s in God’s hand.”

Karisnasamy and his family spent at least two months cleaning up after the 2021 disaster, even borrowing money from friends for emergency repairs to restore their farmland.

This is not an isolated case.

More farmers stop producing rice

Every year, thousands of acres of farmland across various states in Malaysia face the impact of climate change, experiencing floods or droughts.

In Sekinchan, an area referred to as the Rice Bowl of Selangor, rice yield surpasses nine tonnes per hectare, exceeding the national average of four tonnes.

But the unpredictable factors of climate, pests, and fluctuating rice quality have led to a sharp decline in the first quarter harvest of 2023, plummeting to five to six tonnes per hectare.

Sekinchan rice farmer, Sum Ping Nam, 66, blames the unstable weather for damaging the crops.

“The weather is too hot and there is a lack of rainfall. The paddy is not receiving sufficient nutrients, leading to a sharp decrease in yields.”

In the last farming season, he said, the dry and hot weather resulted in low yields of between four to eight tonnes per hectare.

But when there is enough rainfall, he said, yield could go up to 11 tonnes per hectare.

“The climate changed utterly and the timing shifted drastically. When it should rain, there is no rain, and when it shouldn’t rain, it pours,” fellow Sekinchan rice farmer Pua Kim Sui, 69, said.

The farmers said the erratic weather patterns have forced some to shift from growing rice to other crops like guava, calamansi, and bananas, to sustain their livelihoods.

This places further pressure on food security in Malaysia, where rice is a staple but domestic production is only able to sustain 63 percent of local needs.

Bureaucratic challenges

Climate change is not the only reason why growing rice is becoming less appealing to farmers.

Part of it is related to the economics and bureaucracy surrounding rice farming, said Fitri Amir, coordinator of the Malaysian Food Security and Sovereignty Forum.

One key issue is access to seeds.

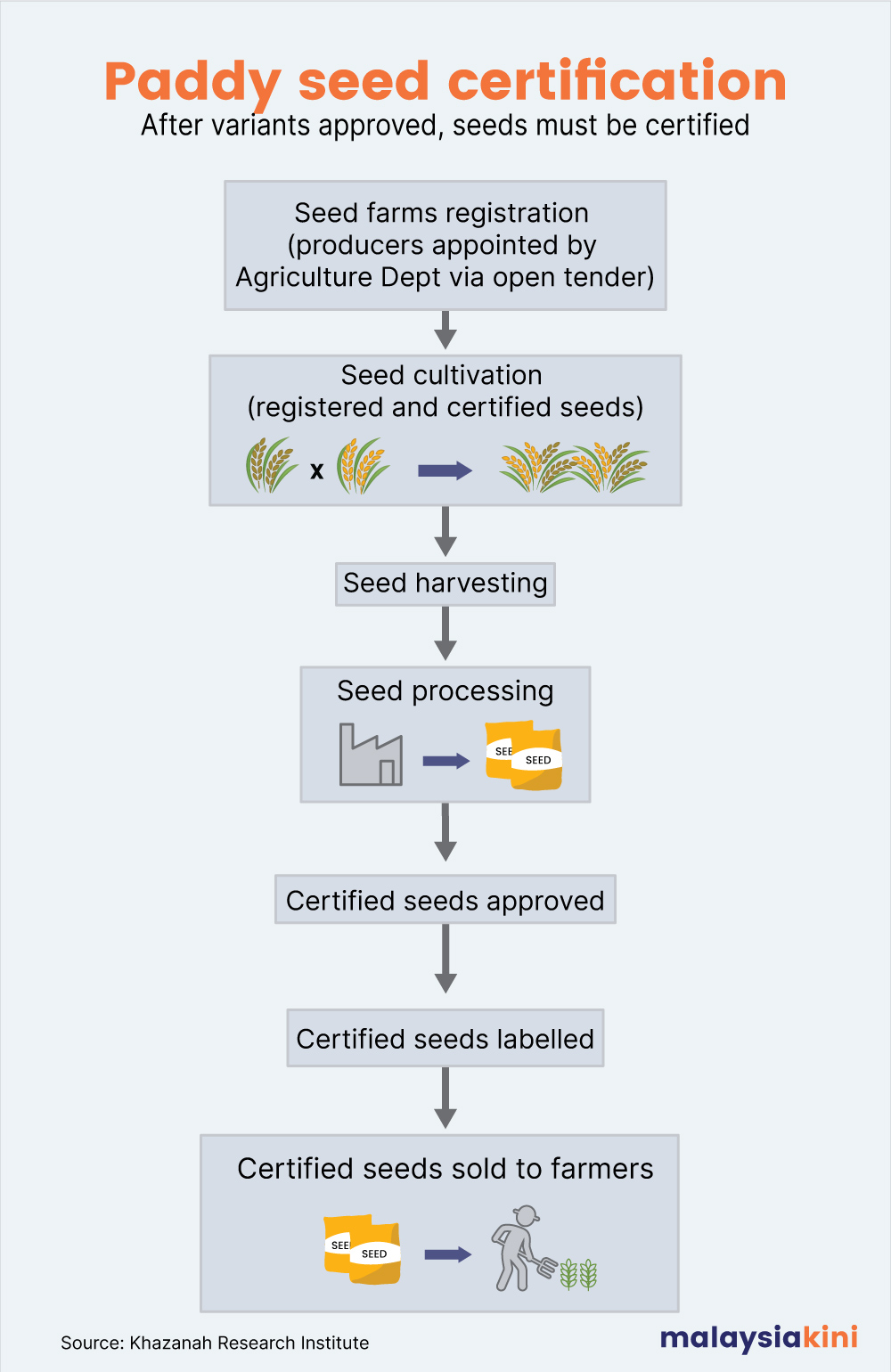

Last month, rice farmers in Kedah were forced to buy seeds on the black market because there were delays in the supply of certified rice seeds from authorised sellers, Kosmo! reported.

Without the seeds bought on the black market, the farmers would have to forgo the year’s sowing season which usually concludes in October.

But it came at a cost. Seeds from authorised sellers cost RM35 per bushel but on the black market, they cost RM52.

“When farmers face difficulties getting the certified seeds in time or need to buy at higher prices, this causes a delay in optimal cultivation timing.

“Sometimes, when they receive the seeds, heavy rains hit and the saplings drift away with the floods.

“The saplings die or become immature, unable to withstand drought, thus resulting in less yield and farmers need to redo the process forcing them to incur extra costs,” Fitri said.

Choosing weather-resistant rice varieties is also crucial. Relying on types that are vulnerable to climate change heightens the risk during extreme weather, making food shortages worse.

This is a challenge for farmers in Malaysia, even though the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (Mardi) was a pioneer in crop breeding in the 1970s.

Today, Malaysia is sluggish in adopting new rice varieties compared to other rice-producing countries in the region. This includes the introduction of varieties which are more resistant to climate change.

Over the last five decades, India introduced over 1,900 rice varieties, the Philippines has over 200, and Thailand boasts more than 80, while Malaysia certified 53.

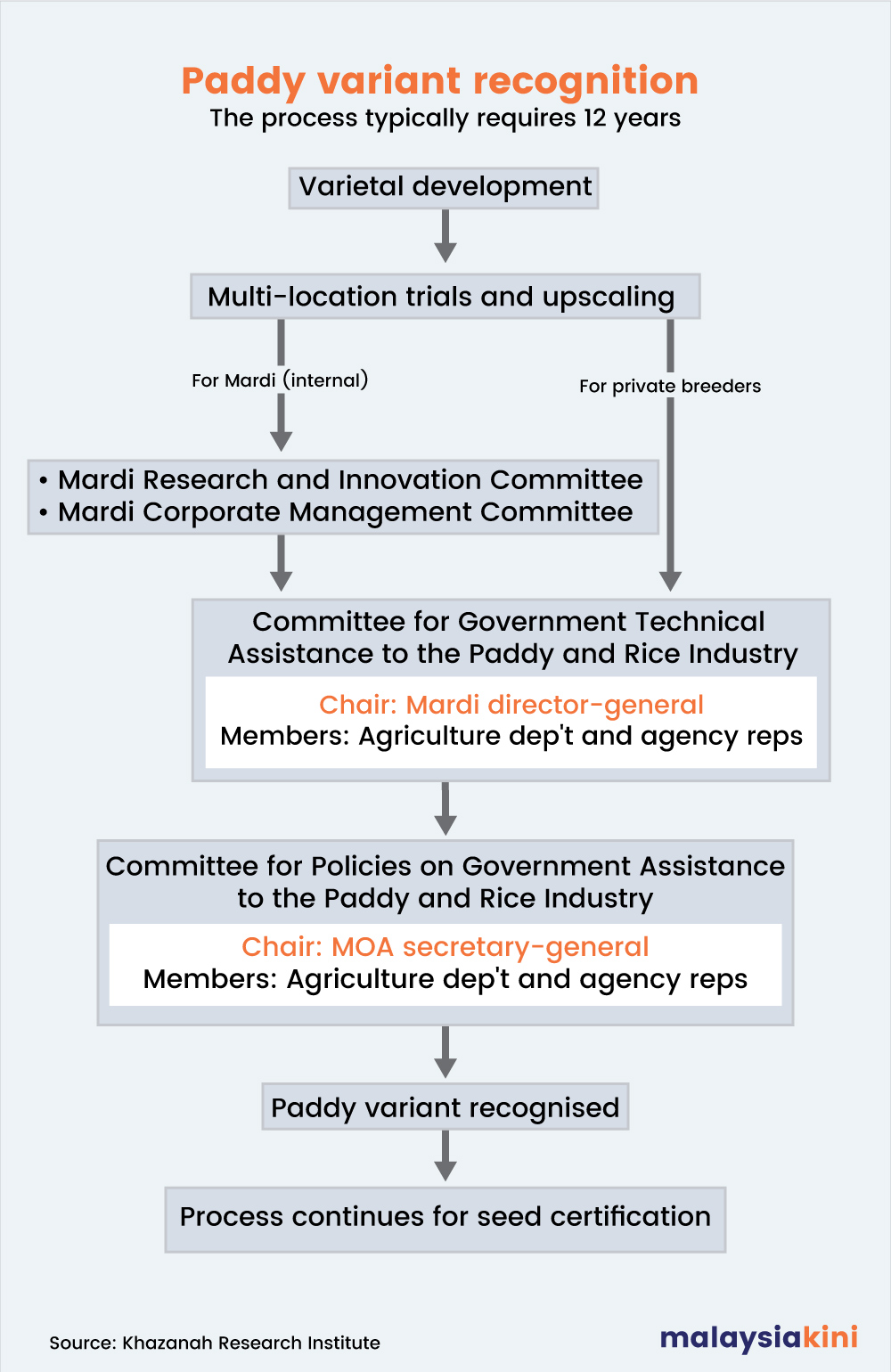

In Malaysia, the research, cultivation, and legal certification of new varieties typically exceeds 12 years, with only 12 licensed rice production companies nationwide.

Fitri said experienced farmers in this country can innovate with diverse seed varieties that can endure extreme heat or rainfall, but getting them to scale comes with challenges.

Laws like Plant Variety Protection grant the breeders of new varieties with exclusive rights to plant those varieties over some time, while other regulations stop farmers from adopting the more versatile varieties.

Farmers are also not allowed to plant varieties that are not issued by Mardi, a move the Agriculture and Food Security Ministry said was to reduce the risk of crop disease, which could be caused by the introduction of external seeds.

Price a big factor

Allen Lim, who manages a rice mill and paddy gallery at PLS Marketing Sdn Bhd in Sekinchan, said the low controlled price of local rice is also a big reason why many rice farmers are moving to other crops.

The price of RM2.60 per kg has not changed since 2008, despite the rising cost of production, he said.

The low prices have pushed some to take on other full-time jobs and become “part-time farmers”, Lim said.

When contacted, Agriculture and Food Security Minister Mohamad Sabu said the ministry is studying whether to float the price of local white rice “to ensure a win-win decision for farmers, the industry, and consumers”.

“Perhaps in the first quarter of this year, there will be an announcement,” he told Malaysiakini.

Vegetable farmers, like Karisnasamy in Kota Kemuning, are also highly affected by prices but this time, due to a lack of controls.

When prices of vegetables go up locally, he said, importers will try to cash in by bringing in vegetables from abroad.

This bump in supplies soon drives down prices, sometimes to rates that are unsustainable for local farmers.

“Loofahs (petola) were selling at RM2.50 per kg but after Thai loofahs came in, the prices dropped to RM1.50 per kg.

“We harvest 300kg a day, making RM450. We need to pay the workers and with that much, it is just not enough,” he said.

Food security advocate Fitri said part of this is due to free-trade agreements which bar us from imposing duties to control the influx of foreign crops.

At the same time, he said, farmers are facing cost pressures from controls and monopolies on agricultural input like fertilisers, seeds, and machinery.

“Why do we have a policy to protect the local car market through the national automotive policy but we don't have one for vegetables to protect our national food security?” he asked.

Farmers lead the way

But those in the field have little time to wait for policies to catch up with their needs in the face of rapidly changing weather patterns.

In Sekinchan, farmers have taken it upon themselves to find ways to mitigate climate change.

This year, mill owner Lim said the Sekinchan rice industry and local agencies collectively shifted cultivation cycles to adapt to the latest weather conditions. The shift took three years to plan.

Traditionally, Sekinchan rice farmers harvest from mid-November to December.

But these days, the volume of rain in these months is so high that it makes harvest difficult, Lim said.

“Therefore, the timing of cultivation has been adjusted. Before the heavy rainy season strikes, the yields have already been harvested by the end of October so that the floods or wet problems won’t affect them.

“This year, we are ahead of the monsoon and farmers are happy with the rice yields,” he said.

While Sekinchan farmers are boasting good yields today, scientific studies project that agricultural yields in general would drop about a third due to changing temperature and rainfall patterns.

This means a greater effort is needed to support farmers to mitigate these changes.

Elisa Azura Azman, a senior agriculture lecturer at Universiti Putra Malaysia said crop rotation, as practised by rice farmers in India, could be one solution.

This means planting other crops after the rice is harvested to rejuvenate the soil and reduce the risk of disease and pest build-up.

“Nevertheless, the farmers should find out about crops that are a better fit. Each crop has specific needs. For instance, our paddy field has clay soil that holds water well but it’s not good for crops that don’t need much water.

“Different crops have different nutrient needs. Crop rotation can help balance nutrient levels in the soil, preventing depletion of specific nutrients and enhancing overall soil fertility,” she said.

Farming revolution

Some farmers have also found a way to take the weather out of the equation - stay indoors.

In the Klang Valley, vegetable cultivation company Farmy has taken up lots in shopping malls to grow vegetables in vertical farms.

Its director, Shoma Tsubota, said staying indoors can guarantee 99 percent of yield.

Not only can they control the amount of light and water the plants receive, but there are also no pests, he said.

Indoor vertical farming uses 70 percent less water, eliminates the need for pesticides, reduces fertiliser usage, and doesn’t deplete soil nutrients, he said.

However, it is not a completely ecological or commercially viable solution.

Indoor farming relies on LED lighting to replicate sunlight and water pumps for irrigation, all of which are powered by electricity. In Malaysia, the bulk of electricity is generated by coal-fired power plants.

It is also still not commercially viable for all crops. Farmy mostly produces kale, which can be sold at a higher price, compared to more commonly consumed and cheaper leafy vegetables like spinach or mustard greens (sawi).

Even so, Tsubota believes it can be a more environmentally sustainable option than shipping vegetables from the highlands into the cities.

“We are in the heart of the city. It takes under 30 minutes for us to deliver to customers. Compared to conventional farms like in Cameron Highlands, it will take a longer time from farm to suppliers than to the store. There’s a lot more energy involved in terms of fuel usage for transportation.

“Logistically, we already reduce the carbon footprint, resources-wise, sustainability-wise, it’s more efficient that way.”

Vertical farms in urban settings are increasingly seen as a way to strengthen food security and sustainability.

It is something that Singapore, a city-state that imports 90 percent of its food needs, sees as a key to its food security.

In 2022, it successfully harvested rice from a vertical farm mounted to a block of residential flats, while the country is investing in vertical farming of vegetables and fish in a bid to produce 30 percent of its food needs.

With climate change, increasing urbanisation, and an ageing population of farmers, such radical shifts in how Malaysia approaches its agricultural policies could be the farming revolution needed to safeguard the country’s food future. - Mkini

This article is produced as part of an investigative journalism project funded by the Asia Democracy Network (ADN).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.