PAS heads to its 69th muktamar at the height of its political power in history. Leading four state governments, with nearly a fifth of the Parliament’s seats (and the largest number at 42), and an unprecedented total of 150 state seats across 11 out of 13 states, PAS is arguably the strongest single party in the country.

With its gains in power, the Islamist party has moved from the ‘extremist’ right to become the centre, or rather, as I suggest below, the centre has moved to them. Its electoral gains over the past year show that PAS has increasingly become a more attractive choice for voters.

At the same time, PAS gaining popularity has resulted in significant changes in how the party operates. Ironically, as PAS has replaced Umno for many voters, it has become more like Umno.

With allegations of corruption and vote buying - leading to the loss of two Parliament seats won in the 15th general election through petitions - and its leaders facing charges for statements that stoke division, PAS is now far from the party led by Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat that controlled the ‘moral political high ground’.

Instead, PAS has become less ‘special’, and more ‘normal.’ As one 45-year-old civil servant in Kuala Terengganu aptly explained during the August special election for this seat: “Before PAS was the party of the extreme, now it is acceptable. I would have never voted for PAS in my life, but now it is okay.”

PAS powerhouse

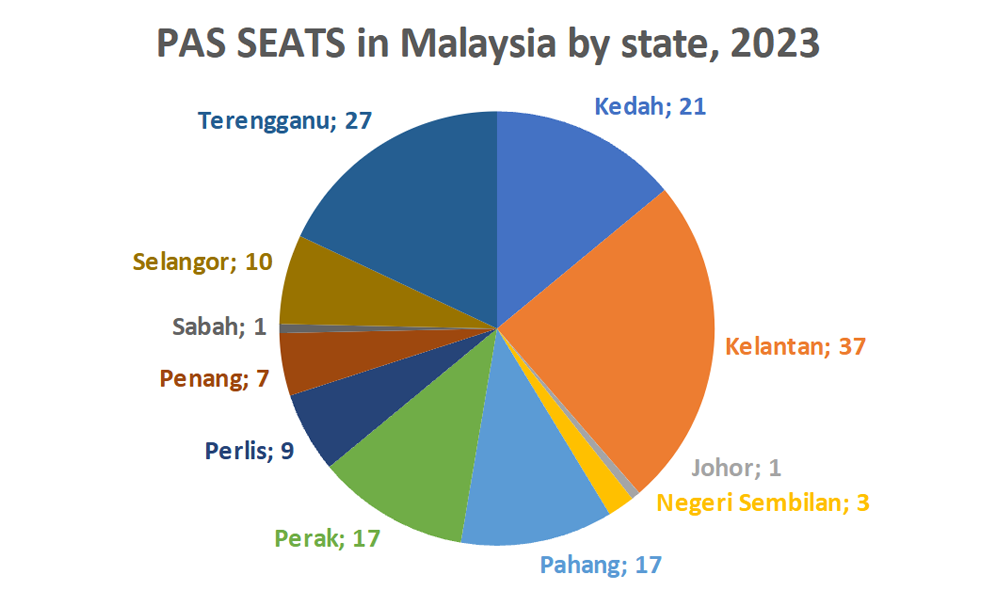

Clearly, more voters agree with him. Not only has PAS gained votes, but the party won seats across the country to become a truly national party, including a foothold in Borneo (although the sole seat in Sabah was through appointment not an election). There are only two places in Malaysia where PAS does not have representation, Malacca and Sarawak.

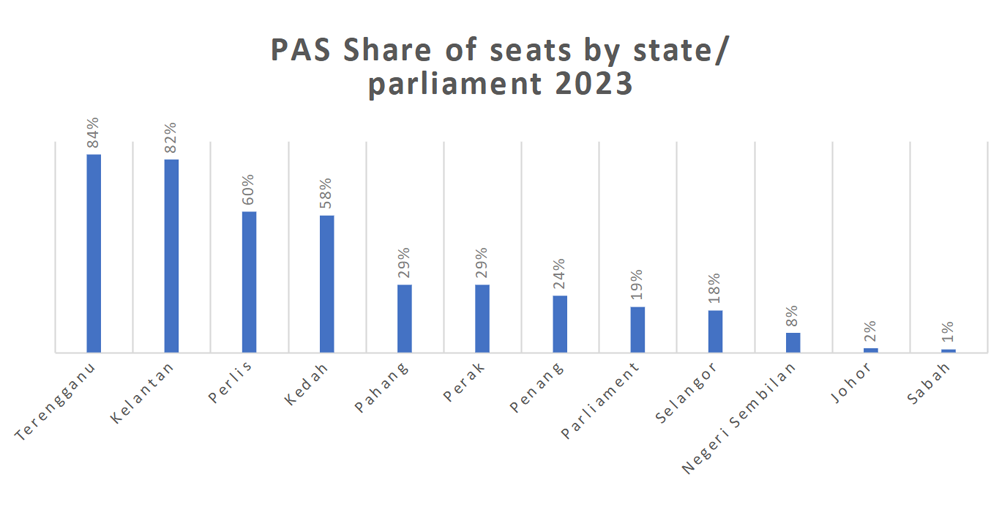

A look at PAS’s share of seats (separate from PN) shows that the party controls the lion's share of representation in the four governments it controls - Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah and Perlis. It also holds a sizeable share of seats in four other states - Perak, Pahang, Selangor, and Penang - as well as the national Parliament. Only in Negeri Sembilan, Johor and Sabah is PAS representation below 10 percent.

Keep in mind that its representation would have been higher in all of these states (except perhaps Johor and Negeri Sembilan) if PAS had not given way in seats for its coalition partner Bersatu. Muhyiddin Yassin-led Bersatu is the weaker player in the Perikatan Nasional coalition in terms of numbers of seats and ability to win votes on its own.

Causes of the ‘Green Wave’

PAS’s ‘Green Wave’ rise to national power has provoked a range of explanations. Most focus on PAS itself: its social roots in religious schools/mosques and provision of social services such as childcare as well as the party’s grounded ties in communities.

Others focus on the appeal of PAS’ more conservative Islamist message, crediting the changing values in Malaysian society of rising conservativism and deepening of religious piety.

There is a myopic focus on youth, who are continually incorrectly seen to underscore the Islamist party’s electoral gains for being touted as more conservative.

If one pays more careful attention to the surveys, the values of youth are not that far off from other age cohorts. Where arguments have had more credence on the impact on youth is the influence of TikTok/social media and emotional campaign appeals.

My own explanations of PAS’s growing political power have focused on five factors:

1) weakness of political alternatives in appeals to the Malay community, namely Umno’s inability to reform itself and address internal corruption in particular as well as Pakatan Harapan parties’ deficits in attracting Malay support;

2) social conditions, not least of which was the Covid-19 crisis, declining social mobility and economic hardships, that have encouraged the rise of the right in Malaysian politics, notably an increase of neo-Malay ethnoreligious nationalism;

3) strategic electoral gains from PAS’s alliance with Bersatu, which have included resources (for campaigns and TikTok influencers) and outreach beyond PAS’ traditional networks; and finally,

4) PAS’ embrace of patronage/populist politics, especially its expanding alliances with business.

5) PAS’ role in the federal government from 2020-2022, which served to confirm among voters not familiar with the party’s first stint at the national level in the 1970s, that the party could be a partner in a coalition government at the national level. After years of demonisation, ironically perhaps the most intense during Mahathir 1.0, the party crossed the federal government threshold again.

PAS strategic positioning

This latter goal was reached through strategic politicking. From alliances first with Pakatan Rakyat, then Umno and most recently with Bersatu, the party aligned itself to gain ‘acceptability’ findings its most comfortable position as the dominant player in an ideologically conservative coalition.

PAS has proven the most willing to strategically reposition itself for power and in doing so has made itself not only the strongest party electorally but made itself the centre of national politics.

While the political manoeuvres have very little to do with its ideological Islamist agenda (and arguably have meant compromising religious principles), the effect has been to move others to PAS and with it, position its ideological agenda in the centre as well.

It is thus not a surprise that Anwar Ibrahim extended an invitation to PAS to join the unity government. Instead of pushing PAS to the margins, in government Anwar has embraced many of PAS’ messages and Islamisation and, in a nutshell, gone to them.

Even among Pakatan Harapan coalition partners, the days of attacking the messages of PAS for its ‘extremism’ have gone, with the pressure focused instead on the comments of individual personalities and leaders.

The new general assembly

In this regard, the 69th muktamar will be important to watch. PAS is unlikely to take up Anwar’s offer as it is quite comfortable where it is (for now): growing in power and the dominant player in the PN coalition.

Nevertheless, PAS’ eagerness and ambitions to return to the federal government are ever apparent. PAS leaders have learned that being in the federal government is a step toward gaining even greater influence.

PAS muktamar traditionally has been about the party and internal debates. This time the party will have to move beyond itself. As PAS is now dominating the political centre, the meeting will have greater attention and greater expectations.

Given PAS’ new political strength, the muktamar parallels the new Umno general assembly, not just in the lack of competition for senior leadership positions in the party polls.

It is coming at a time of electoral gains through August 2023, but also after its support levels have plateaued in subsequent losses in the by-elections of Simpang Jeram and Pelangai.

This muktamar will be a test of whether the party’s discourse and calibre meaningfully engage national issues; it will test whether the party is in fact at the stage to be the centre. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honourary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.