|

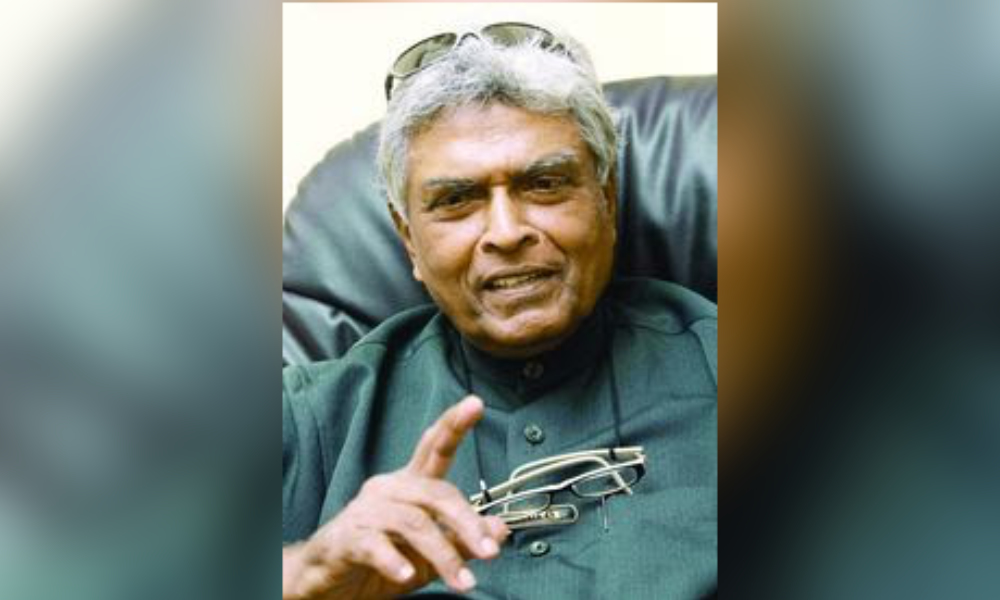

In medicine, he was a no-nonsense doctor, especially on matters of medical ethics. On the cricket pitch, he was always in his element - even sharing a rugby joke or two, being out with the boys.

While Malaysian cricket lost a formidable cricketer in Emeritus Prof Dr Alex Ernald Delilkan who passed away on Feb 20 - the Malaysian medical fraternity lost an outstanding anaesthesiologist, academician, clinical ethicist as well as trauma, pain management, and critical care expert.

Commencing in the 1950s, Delilkan’s medical career and his engagement with cricket ran parallel. And in both fields, he clocked up a lifetime of good innings.

In a brief and poignant tribute to Delilkan, the Universiti Malaya Medical Alumni aptly issued this encomium on his behalf:

“In fond remembrance of Emeritus Professor Datuk Dr Alexius Ernald Delilkan, whose life’s journey has reached its final innings. He leaves behind a legacy that transcends the boundaries of the cricket pitch, the lecture hall, and the operating theatre alike. Prof Delilkan was not only a distinguished anaesthesiologist but also a true teacher and a revered leader who orchestrated the game of life with the precision of a skilled bowler and the compassion of a doctor.”

A skilled bowler, yes, and a deftly competent batsman too.

In 1966 at the Selangor Club field, Delilkan unwittingly cocked a snook against world-renowned cricketer Gary Sobers of the West Indies before a crowd of 10,000.

Sobers was a highly skilled bowler, an aggressive batsman, and an excellent fielder who was widely considered to be cricket's greatest-ever all-rounder and one of the best cricketers of all time.

When Delilkan bowled out Sobers, there was absolute silence in the field for a good five seconds before the “time-delayed hesitant applause” rang out with little gusto.

This was followed by boos as the crowd had come to see Sobers in action, not a Sobers humbled by Delilkan.

Later in the dressing room, English cricketer Jim Swanton told Sobers that the crowd was disappointed that he was bowled out by a lesser-than-great Malaysian cricketer.

For the record, Delilkan was an outstanding sports stalwart in Malaysian cricket from 1955 to 1972 - even captaining the national team from 1959 to 1972. The other feather in his cap was that no other Malaysian, except Delilkan, was invited to play with the distinguished International Cavaliers of England.

Milestones in medicine

Delilkan’s life and times as a cricketer and doctor seem to yield storylines that are both triumphantly momentous, epochal, and surpassingly anecdotal. From cricket’s green patch, success continued to trail the doctor in the medical field.

Delilkan made history when he established the country’s first intensive care unit at the then-Universiti Hospital in Petaling Jaya in 1969. This was two years after the teaching hospital became an indelible landmark in Lembah Pantai.

It was in 1953, when Danish anaesthetist Bjorn Ibsen, suggested that positive pressure ventilation should be the treatment of choice during Europe’s polio epidemic - and at the same time, Ibsen set up the first intensive care unit (ICU) in Denmark - which eventually advanced to being recognised as a new speciality in medicine.

However, the jury was still out on this at that time in Europe. The idea of including this new specialisation in medicine went on pause mode as questions followed: Is this new speciality an urgent necessity? Would it flop or on the other hand, will it distinctively become modern medicine’s jewel in the crown?

Sixteen years later, the young specialist in Delilkan, sensed an inkling that Ibsen’s critical care outfit in Copenhagen was the perfect prototype, that would rightly initiate a new renaissance, in contemporary medicine, specifically in the area of critical patient care.

Delilkan cobbled together a collage of positive and inspiring clinicians and other auxiliary staff to ordain not only the first critical care unit in the country but also the first one in Southeast Asia.

This was in the 1960s, and old Malaya was a developing country (and still is, perhaps). In that erstwhile period, the term ICU was already a byword uttered by the local medical community. And thanks to Delilkan, simple Malay and non-English speaking folks will say wad sakit tenat.

Moving forward, as the country’s first qualified “academic anaesthetist”, Delilkan was invited to formulate the preliminary draft for the training of postgraduate students and certification in anaesthesiology in 1978.

He also headed the anaesthetic teams involved in the first successful separation of conjoined twins in the country in 1981, and the first successful delivery of quintuplets in Malaysia in 1996.

Delilkan was often invited to the courts to lend his thoughts on medico-legal issues where he willingly contributed his time as an expert witness and friend of the court.

Delilkan was always passionate about anaesthesiology, critical care, trauma medicine, and pain management - specialities that would bring him close to the very source of the human spirit and its brokenness.

He would often instil in his medical ethics lecture: “Do not just treat a broken tissue or broken bone. Look at your patient as a human being, and one with a broken spirit also. Then treat both infirmities.”

At the lecture hall with Delilkan

Students as well as nursing and other medical staff who attend his lectures, say Delilkan is very engaging, entertaining, and refreshingly insightful of issues in clinical ethics.

According to some, he prepares his lecture papers with every possible detail included and even offers arcane case studies that are stunning eye-openers.

In his anaesthesia class, Delilkan would emphatically draw attention to the fact that administrating general anaesthesia is not as routine: “Surgery can be minor or major but administrating general anaesthesia is always major.”

There is no such thing as a “whiff of gas”, Delilkan will accentuate this oft-repeated mantra to knock home the point.

In the same breath, he will offer a chilling caution: “For every 250,000 surgeries performed under general anaesthesia, one would turn awry. Remember? It is more than just a whiff of gas!”

Then quite unexpectedly, medicine’s wicketkeeper of ethics would introduce a surprise element: “I love to watch football, but I cringe when a player falls in a bad tackle and is injured.

“You see, medics will then run into the field with an anaesthetic canister to spray a ‘whiff of gas’ on the injured limb.

“After a few seconds, the player gets up and tests the ability of his injured limb. He then sprints into the field heroically and the crowd roars and applauds, and he continues to play football.”

According to Delilkan: “The anaesthetic spray only momentarily numbs the injured area to mask the pain. But pain is a symptom to warn the person that something is wrong and to immediately cease all activity. When the player runs back into the field to play more football, unknowingly he is causing further damage to tissue, bone, and ligament, which eventually becomes the orthopaedic surgeon’s nightmare.

“You see, a ‘whiff of gas’ whether administered in the operating theatre or the football field always comes with a hidden danger,” Delilkan says, adding: “I wonder, what are reserve players for.”

Delilkan’s humility laced with charity in his relationship with his students and patients as well as his lecture audience is legendary. Whenever he takes the podium, he avoids pontificating from a high pedestal. No airs whatsoever.

To borrow his oft-repeated metaphor, his lectures are more than just a “whiff of gas” as they are always exuberant, riveting, and meaningfully in-depth.

Delilkan simply speaks in his unmistakable own genre - “Delilkan-nology”. This also means, that his lectures are not without the occasional discordant note - or “controversy”, which comes, much to the medical fraternity’s unease and nervousness.

Sometimes his sarcastic witticisms come into play, but they never cease to be an entertaining novelty as well. Once during a lecture at the teaching hospital, he said: “Modern hospitals want to go paperless. I just went to the gents and realised that the toilet is also paperless. No toilet paper lah!” he joked, lending a lull to his usually institutional-type of lectures.

Upfront best

In a lecture on medical ethics for nursing staff at the Tun Tan Cheng Lock Nursing School in Assunta Hospital decades ago, Delilkan was at his upfront best.

Giving an example of poor medical ethics in organ transplant surgeries, Delilkan shared this story: “A pair of twin babies, both girls, were born at a hospital in Selangor. One baby was born with a withered hand, and the other was born with its brain outside its skull (anencephalous).

He said the baby with the brain issue would probably die, while the baby with the withered hand would live.

“Surgeons at the hospital decided to transplant one hand of the baby born with anencephalous to the baby born with the withered hand, after obtaining consent from the babies’ parents. The surgeons had good intentions. This, considering that the siblings were identical twins and organ rejection would be unlikely.”

He said: “The transplant was a success and a gala press conference was held at the hospital with local and foreign media present, including CNN.

“However, I was eventually informed that the donor baby was left to die unceremoniously. This is very unethical, it is a crime. In such circumstances, the donor baby must be returned to its original health status and cared for in every way, till it died a natural death.”

He said medicine is not a zero-sum game, where one side’s gain comes at the other’s deficit. Delilkan was visibly disturbed as he concluded his story.

Later during tea break, he spotted me and asked: “Oh what are you doing here? I thought this lecture was for nurses only,” he smiled.

“Okay, but if you are writing this story, please do not mention the name of the hospital where the transplant took place, you know how ‘they’ will crucify me.

“I have always spoken truth to power! Now, I am a semi-retired emeritus prof, kind of weary with frequent run-ins with the powers that be, got it, Joe?” he asked.

I nodded. When I returned to the news desk, I did not mention this part of his lecture at all in my story. Today, as I expose this scoop, I will still keep my promise to the good professor - no finger-pointing of the hospital that committed this crime.

‘Bury the brain dead’

The second part of his lecture at the same venue touched on the misuse of the ICU facility. Ironically, the man who introduced the wad sakit tenat to the country rued that the very facility he helped to establish in the 1960s was being misused today.

Delilkan promptly declared: “Bury the brain dead. The brain dead must be buried, simply because they are no longer alive. If you believe that the brain dead must be buried, you are dead right!”

At this moment, there was palpable silence and the eyebrows of the nurses went a notch higher - nonplussed by Delilkan’s take. But he proceeded to say that there is no reason to keep these patients “artificially” alive because they are dead.

“What is keeping them alive are the modern machines in the ICU. These ‘dead man walking types’ are occupying precious space in our ICUs, space that would be useful for critically ill patients who are alive, such as those who are in a vegetative state.

“The status of these patients can be reversed because brain activity is still evident.”

He went on to rightly explain: “A determination of death must be made by the accepted medical standards, and must additionally include one of the following; Irreversible cessation of circulatory and pulmonary functions. Irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain and that includes the brainstem. It is at his stage that the lifeline must be unplugged.”

Like every “bad journalist”, returning to the news desk, I typed my story, latching on to Delilkan’s shocking one-liner for the headline: “Bury the brain dead: Expert”. I took this slant, obviously to get readers’ rave attention and earn a front-page sensational splash in my tabloid.

My editors who are usually sharp-edged at red-flagging such flagrant “turn of phrase” missed this ill-favoured blotch this time and it went into print.

The story appeared on page six of the tabloid the following day. The then Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur and Malaysia’s first cardinal, His Eminence the late Anthony Soter Fernandez was disturbed by the headline in the story.

He called me and bluntly reprimanded me: “The headline in your story lacks charity. You must be prudent and always be kind to the unfortunate. I am not quarrelling with science or the medical expert, maybe he is right.

“But at this time, there are so many people keeping vigil at ICUs throughout the country. How would they feel after reading your story? So long as there is life, there is hope,” he countered.

I sheepishly apologised to the prelate and admitted responsibility for the gaffe. I should have known better that the Church, the clergy, and the faithful (including me) are pro-lifers - but I hardly expected the local patriarch to call and issue his stand on the matter.

A legacy lives on

When Delilkan retired in 1989 at the age of 55, he was rehired the following day by the medical faculty of Universiti Malaya.

As emeritus professor, he continued to work - striding the corridors of academia like a colossus. And like a battery that was not close to running out, the cricketer-doctor cruised into millennium 2000 stridently.

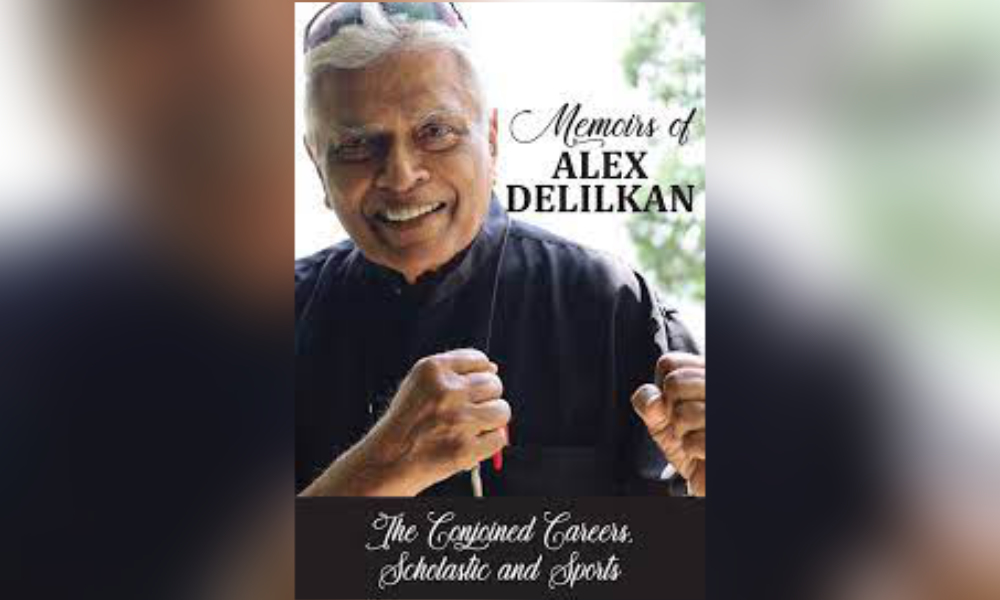

Teaching and lecturing, giving his time to the courts, writing one book after another, Delilkan seemed not to be affected by fatigue and ennui, such that, one wondered from where he derived a constant surge of voltage to stay on his toes, since his long haul from the 50s.

His son Rienzie, speaking on behalf of his family, lent this accolade: “We as a family treasured our dad’s love for our mum (Prabha Senan), and all of us siblings (Anne, Melanie, and Sharu). He might have been a giant in his fields of expertise, but more importantly, he was, is, and will always be part of us (including five grandchildren).

“He loved, trusted, and supported us to the hilt, he empowered all of us, and he was a great husband and father to the family. His legacy lives on in every one of us. We will miss him dearly.”

Delilkan’s shadow looms large even in death at the very ripe old age of 90.

A memorial card designed by his family declares that his legacy will continue to live on - just as Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore offered in his hallowed narrative: “Death does not mean extinguishing the light. It just means, putting off the lamp, because a new dawn has arrived.”

Rest in peace Delilkan. - Mkini

JOSEPH MASILAMANY is a veteran journalist.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.