QUESTION TIME | Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng's statement that the government has managed to bring down the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio by reducing expenditure needs some critical analysis to see how much of what he says can be justified.

Lim said: “One example has been the ability of the government to control and reduce its overall debt and liabilities to 75.4 percent of the GDP in 2018 from 79.3 percent in 2017, as announced by the newly established Debt Management Committee.

"Despite a rise in direct government debt, overall government debt and liabilities dropped 3.9 percentage points due to successful cost rationalisation of both overpriced megaprojects and public-private partnership (PPP) payments.”

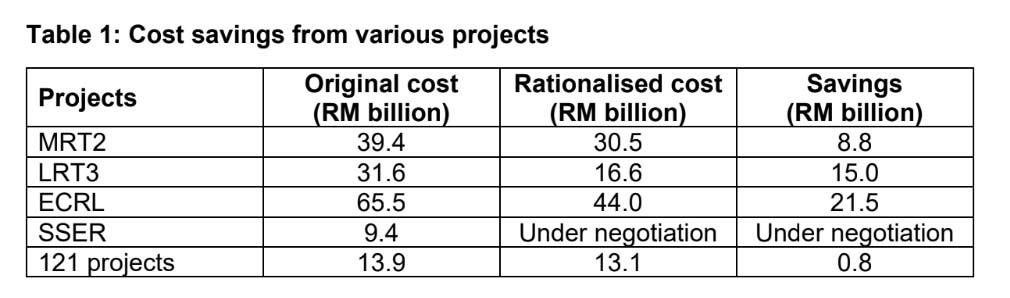

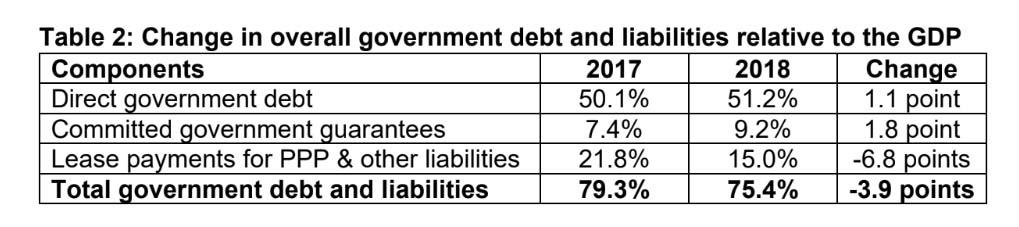

Lim uses two tables which I reproduce to explain his statement. Table 1 shows the cost savings he claims were made, which reduced the debts and liabilities as a percentage of GDP, while Table 2 breaks down the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio according to the category of debt and liabilities.

(GDP is gross domestic product, a measure of goods and services produced in the economy in a year. The debt-to-GDP ratio is a measure of the indebtedness of a country relative to its output - too high a level indicates that debts may be too much.)

There are two areas where we can take issue with part of Lim’s statements. The first one involves Table 1, which states that there is an RM21.5 billion saving in the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) costs. This "saving" was negotiated and announced by Daim Zainuddin only about two months ago.

Therefore, it cannot be reflected in the end-2018 balance sheet items for debts and liabilities, and could not have contributed in any way at all to debt reductions during the period. It is wrong to say that they have, as Lim did.

Note: SSER refers to a pipeline project undertaken by a China company.

Note: PPP stands for public-private partnerships, arrangements whereby the private sector funds and undertakes government projects in return for long-term repayments.

The second point: Lim’s Table 2 shows how the debt-to-GDP ratio changes according to what Lim says are the three components of government debt - direct government debt, committed government guarantees and lease payments for public-private partnerships and other liabilities.

This shows that the increase in government debt and government guarantees respectively increased the debt-to-GDP ratio by 1.1 and 1.8 points respectively, with only lease payments for PPPs reducing the ratio - by a large 6.8 points. That means direct government debt and guarantees actually increased during the period, while lease payments substantially reduced.

It becomes even more unclear now how the cost savings in Table 1 translated to a lower debt-to-GDP ratio when the main advance in terms of reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio came from lease payments related to PPPs.

The Debt Management Committee, in its statement attempting to explain this, had said that “as of end-2018, the total debt and liabilities of the government stood at RM1.1 trillion, or approximately 75.4 percent of the GDP. This was partly due to an RM54.2 billion rise in direct government debt to RM741.0 billion, from RM686.8 billion in the previous year.

"The rise in debt was used to finance the fiscal deficit, especially for expenditure arising from PPP lease commitments and off-budget spending that were previously not transparently included in the budget.

“Total committed government guarantees that are paid by the government, to finance ongoing public transport projects like ECRL , MRT (Mass Rapid Transit) and LRT (Light Rail Transit) also rose. The increase in committed government guarantees was not caused by any new infrastructure projects, but instead was due to the need to finance existing ones. In other words, the rise in liabilities is to fund projects that were approved under the previous administration.”

This seems to indicate that as lease payments for PPPs and committed guarantees that are likely to be called materialise, they are transferred to the government debt account.

If this internationally used debt-to-GDP ratio is used, then the ratio goes up from 50.1 percent at the end of 2017 to 51.2 percent at the end of 2018 - still well within acceptable levels.

However, Lim has insisted in lumping government guarantees and other liabilities into government debt to raise the debt-to-GDP ratio, and then as a result of the reduction in PPP liabilities, claims that the ratio has fallen to 75.4 percent from 79.3 percent previously.

That reduction, as we saw, is entirely due to a reduction of PPP liabilities, which accounted for 6.8 points in the debt-to-GDP ratio, as arbitrarily defined by Lim in defiance of international convention.

I have examined the issue of debt over one year ago, after Lim had just become finance minister where I disputed his assertion that government debt was over RM1 trillion, and said that it was over RM1 trillion only if you included government guarantees and PPP liabilities.

I am not alone here. Rating agency Moody's, in a recent report, put Malaysia’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 51 percent. “Malaysia’s debt metrics is weaker, but it does not mean it cannot service its debts,” said Anushka Shah, a vice-president of Moody’s overseeing Malaysia’s sovereign risk. According to her, default risk is limited because there is low foreign-currency exposure to government debt and most domestic debt is held by large and stable investors.

According to one respected source of data commonly used by analysts to compare countries, CEIC, Malaysia’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased to 51.2 percent at the end of 2018 from 50.1 percent previously.

Internationally, people are not using Lim’s measure of debt-to-GDP. If Lim’s figure is used, Malaysia is unfairly disadvantaged in international comparisons, surely something Lim does not want.

These data sources indicate a much better picture of Malaysia’s debt than painted by Lim, who may be exaggerating things for political purposes and to show how much he has purportedly done to reduce the debt burden.

Also, PPPs have become an accepted way of lightening the government’s debts by getting the private sector to finance projects and paying them periodically over long periods of times, provided the projects are awarded fairly.

This is reflected in the government’s operating expenditure as lease payments and therefore should not be reflected again in the balance sheet. That’s double counting.

If Lim wants to stick to his non-standard format, he has to do at least two things - list and disclose the guarantees the government has made, and explain why they should be classified as debt. Do the same with all the PPP-related liabilities and explain why they should be considered debt.

If he does not do that and answer the questions raised here, his claims must be taken with a huge pinch of salt and seen as something which is meant more for politics than in pursuit of the financial truth.

P GUNASEGARAM has over the last 40 years pored over government accounts as a financial journalist and editor, an equity analyst and research head at foreign and local stockbroking firms, and as a consultant. E-mail: t.p.guna@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.