PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang ended the party’s 65th muktamar by predicting a collapse of Pakatan Harapan. This should come as no surprise, as in the assembly he harped on the alleged failures of the government. The party has been engaged in trying to promote divisions in and dissatisfaction with Harapan since GE14.

At the same assembly, Hadi received formal approval from the delegates for a partnership with Umno, a de facto relationship that has existed electorally post-GE14 but one in practice started much earlier. The move signals a change in the alliance at the leadership level to greater grassroots ties.

There is little recognition that the conditions Harapan faces were the product of Umno mismanagement, or any articulation of how PAS would manage the challenges the country faces. PAS is engaged in a full-on attack on Harapan, with the hope that it will bring PAS into national power.

Of the two parties in the opposition, PAS has proven (so far) most adept at navigating New Malaysia’s politics of uncertainty and has gained political traction over the last year. There have been important changes taking place in the Islamic party in recent years. PAS is clearly engaged in a ‘waiting game’ in which national power remains an ideal, but its influence in shaping the national narrative and political landscape has grown.

Despite predictions that PAS would be wiped out as a political force, its role in Malaysian politics is more important than ever.

A ‘purist’ path

Since PAS left Pakatan Rakyat in 2015 and internally split (with former PAS leaders forming Amanah later that year), the party has rested its political fortunes on three organising principles.

First, has been that it is ‘open’ to members of the ‘ummah’ – willing to accept new supporters and cooperate with different players as long as they are Muslim. This has included extensive outreach to traditional Umno members and has underscored the deepening of relationships outside of the party’s traditional base.

This has been accompanied by the second principle that it is independent, able to choose its own path and maintain control over its choices. PAS wants to lead, rather than compromise on its ideals.

Third, it has based its political strategy on the idea of a ‘Green Revolution’ – a dynamic in which the demographic conditions of an increasing Malay population with greater religious piety will work in its favour electorally.

This ‘purist’ ultra-religious nationalist path – propagating the faith on behalf of the faithful community – has meant that PAS has become more like the Umno that former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak had branded – adopting racialised chauvinism, exclusionary membership and envisioning a Malaysia for some rather than all – clear steps away from the position PAS adopted with ‘PAS for all’ while part of Pakatan Rakyat.

PAS returned from a position where it was touted as inadequately protecting Islam – claims that were made against the party in 2013 – to one in which it has assumed the protector label again, although one, as will be developed below, that is based on a narrower version of the faith.

From national to regional fortunes

These strategic decisions affected the party’s performance in GE14. Two significant developments occurred. The party moved from being a national party to a regional one. With its victory in Terengganu, the party made gains in seats, as well as holding onto Kelantan. Its wins were in the East Coast.

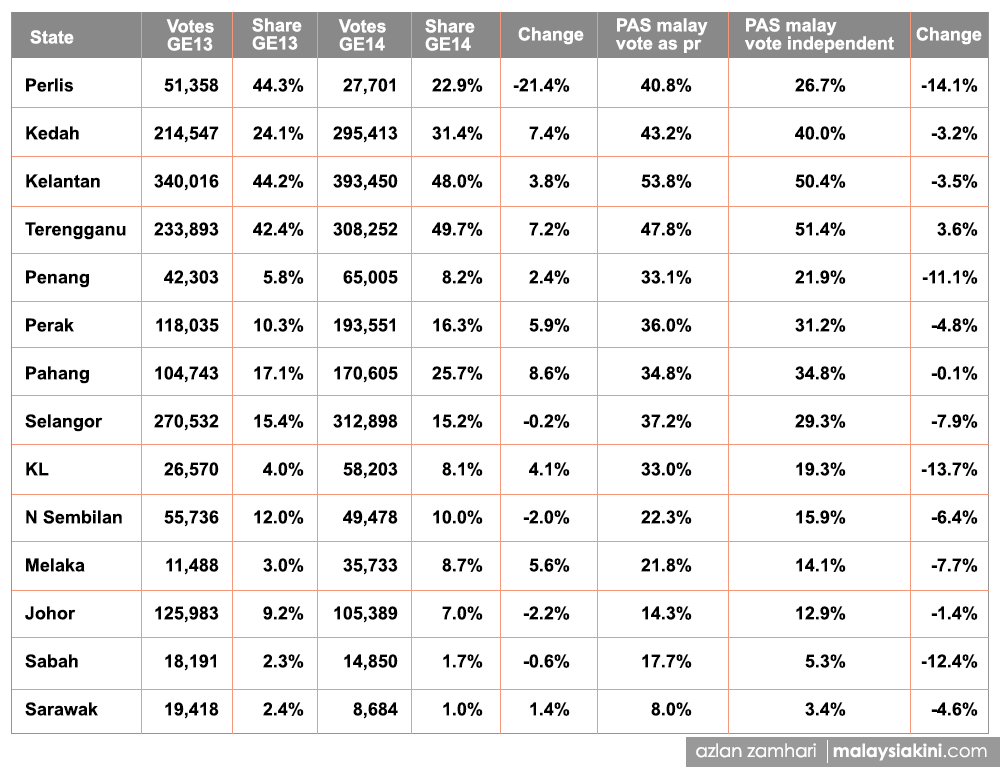

A closer look at the results, however, show that PAS made the most gains in terms of vote share in Pahang, and did also increase its vote share in Perak and Malacca. Overall, its vote share did not drop significantly, except in Perlis, but with a move away from cooperation with multi-ethnic parties, its chances of winning power and seats nationally declined. The fact that its splinter party, Amanah, went into national government only served to showcase that different decisions in 2015 would potentially have led to a different role.

What is not appreciated however is that the ‘Green Revolution’ strategy did not work that well. In fact, PAS did not gain a greater share of the Malay vote out (rather than inside) of the Pakatan coalition. Based on estimates at the polling station level, the only state in which it gained a larger share of the Malay vote is in Terengganu (although in Pahang the share of Malay vote did not drop).

The party did not hold onto as much of the electorate as it hoped, and importantly, the ‘open’ and ‘protector’ strategies were only marginally effective among the Malay electorate. PAS did however increase its share of younger Malays in some states, especially in Terengganu.

Partnerships of political convenience

Given the ineffectiveness of going it alone, it is thus not surprising that PAS has formed a political partnership with Umno. By riding on a Najib-weakened Umno and adopting even more ultra-religious nationalist rhetoric (with recent comments of no vernacular schools as an example), PAS hopes to gain a larger share of the Malay electorate (and Umno in turn hopes to have a post-Najib resurrection).

The results from the eight by-elections since GE14 show two trends – PAS has not significantly gained vote share (with BN in GE14, it would have won 38.2% of the vote, and over the eight by-elections, the share is 35.7% of the vote with BN) but its share of the Malay vote has increased as shown in the contentious by-elections of Cameron Highlands, Semenyih and Rantau.

PAS was seen as decisive in shaping the outcome in each of these results, thus giving the impression of greater electoral strength. The Umno partnership is thus seen as a path for PAS as a vehicle for the national stage.

It is also one fraught with difficulties, as despite a groundswell of support for the partnership, there are residual reservations in states where PAS and Umno have been traditional political competitors – notably Kelantan, Terengganu, Perlis and Pahang – which explains why there is resistance to forming joint governments. Old resentments and suspicions remain.

The second obstacle is one of trust. PAS has shown historically that a lack of trust (along with ambition) undercut earlier partnerships. For now, the balance of power between Umno and PAS is less central than defeating Harapan, but ultimately these issues will strain any alliance.

Finally, as PAS adopts Umno racialised rhetoric as Umno adopted PAS religious rhetoric, differentiating the two parties will become difficult. This is further complicated by common practices of patronage and persistent concerns about financing. In choosing to ally with Umno, PAS is now locked in a pattern of trying to out-Umno on issues of religion and race, pushing it further toward greater ultra-religious nationalism and racism.

PAS simultaneously has recognised that New Malaysia is fraught with uncertainty and political relationship are becoming more tenuous. The reality is that Malaysia is moving away from stable political coalitions to more fluid ones, with the potential of these coalitions increasingly formed after elections as is common elsewhere.

PAS has opted to extend an olive branch to Bersatu and party leader Dr Mahathir Mohamad. Politically, New Malaysia means that all coalitions are possible. The question is what are they based on, beyond political convenience.

‘Protector’ of the faith

PAS claims however that its Islamic agenda is at its core. This has gone through a meaningful shift as PAS has adapted its political strategy post-2015 and changes in political Islam globally and moved religious agendas further away from democratic inclusion towards identity politics. For many, with charges of corruption continuing to circulate, PAS has been seen to lose its moral compass.

The open racism in PAS’ 65th muktamar reached new heights. While a few leaders tried to address the damage caused by comments on vernacular schools and the demonisation of non-Muslims, there is a deepening of antagonism toward PAS for these positions. This feed racial polarisation in Malaysia, a dangerous trajectory that feeds Islamophobia and anger. PAS should understand that there will be a backlash, as exclusionary views only undermine their national ambitions. Umno and PAS cannot govern Malaysia alone, despite their misperceptions and actions that suggest otherwise.

PAS’ move to the right is not just about ‘others’ but also about Muslims, and how the party is portraying the faith. For decades, PAS has propagated a view of Islam as conforming to conservative interpretations of law and behaviour. The focus on legal provisions of syariah emphasises punishment. When PAS engaged politically outside of its traditional base, ideas of fairness, justice and democracy entered into the rubric – strikingly missing in the recent muktamar discussions.

Islam is being portrayed negatively – follow rather than find, fault rather than forgive, and exclude rather than embrace. The reality is that this vision does not fit with many in the cosmopolitan Muslim community in Malaysia. PAS is not protecting the faith but pushing its own narrow version of the faith.

No passing of the baton

This ultra-religious nationalism is Hadi’s legacy. He continues to hold onto power. All the major leadership positions were uncontested in the party’s election, with only one new face as vice-president, Terengganu menteri besar Ahmad Samsuri Mokhtar (an expected rise given his strong performance in Terengganu) and a new ulama chief, Nik Muhammad Zawawi.

The central committee – with nine ulama and nine professionals – maintains a pattern of Hadi loyalists (not only to him but to his efforts in moving the party to its ultra-religious nationalist position) and speaks to the continued power of the East Coast in leading the party. For now, the party retains the Hadi brand.

This said, the election suggests the rise of new blood, different ideas and greater inclusion across Malaysia. There are more professionals in the youth leadership, with more cosmopolitan awareness. The question is whether they can offer different inputs and move the party away from the more extreme and precarious direction it is taking. Here too, PAS is in a waiting game.

BRIDGET WELSH is an associate professor of political science at John Cabot University in Rome. She also continues to be a senior associate research fellow at the National Taiwan University's Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and The Habibie Centre, as well as a university fellow of Charles Darwin University. Her latest book is the post-election edition of ‘The end of Umno? Essays on Malaysia's former dominant party.’ She can be reached at bridgetwelsh1@gmail.com. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.