In January 2016, seven people detained by the police stepped out of the shadows to tell the world of the horrendous ill-treatment they suffered in Bukit Aman, the police headquarters.

Recalling how they were made to perform degrading acts such as kissing a dirty floor, stripping, being forced to watch pornography, and perform sexual acts in the presence of the authorities, these seven detainees were not alone in their revelations. A week later, another six detainees revealed that they had been subjected to similar torment.

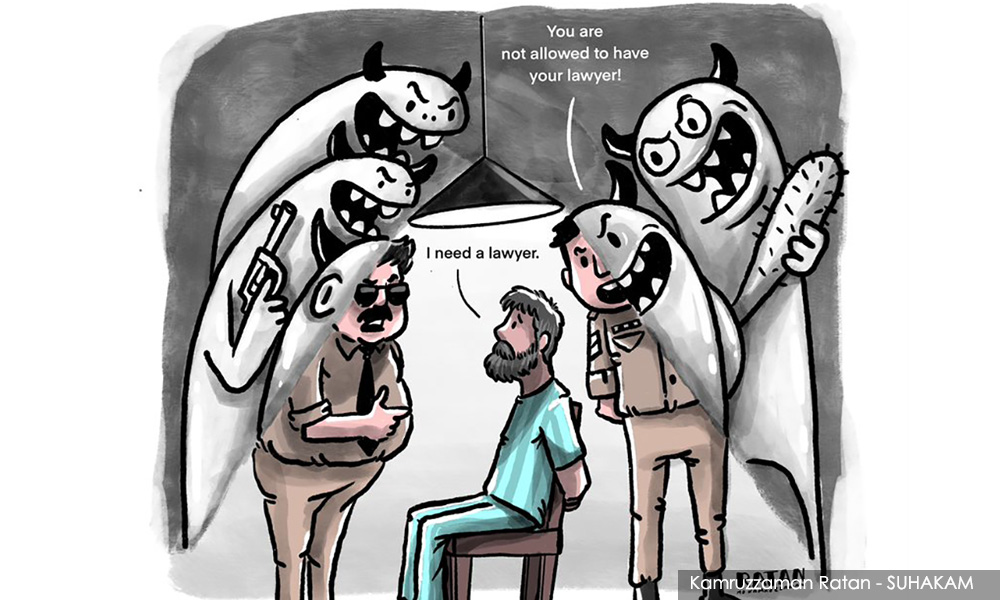

All 13 detainees were held under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (Sosma) – one piece of legislation in the country's arsenal of laws unfriendly to human rights, which includes the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2015 (Pota) and Prevention of Crime Act 1959 (Poca). Concerns abound as these laws permit varying periods of detention without trial and give room for torture and ill-treatment to take place.

The short-lived moratorium on these security laws last year continues to show that the Malaysian government and authorities are not prepared to make bold steps in repealing these oppressive laws that open avenues for the torture and impunity for those held in custody, that goes in tandem with a multitude of cases of deaths and torture in custody.

According to the latest Human Rights Report of NGO Suara Rakyat Malaysia (Suaram), the number of deaths in police custody has significantly reduced since 2016 but the issue of torture, degrading or inhuman treatment in detention remains an unresolved concern. It is easy to throw statistics and to show trends, but one life lost or tortured due to inhuman treatment is one too many.

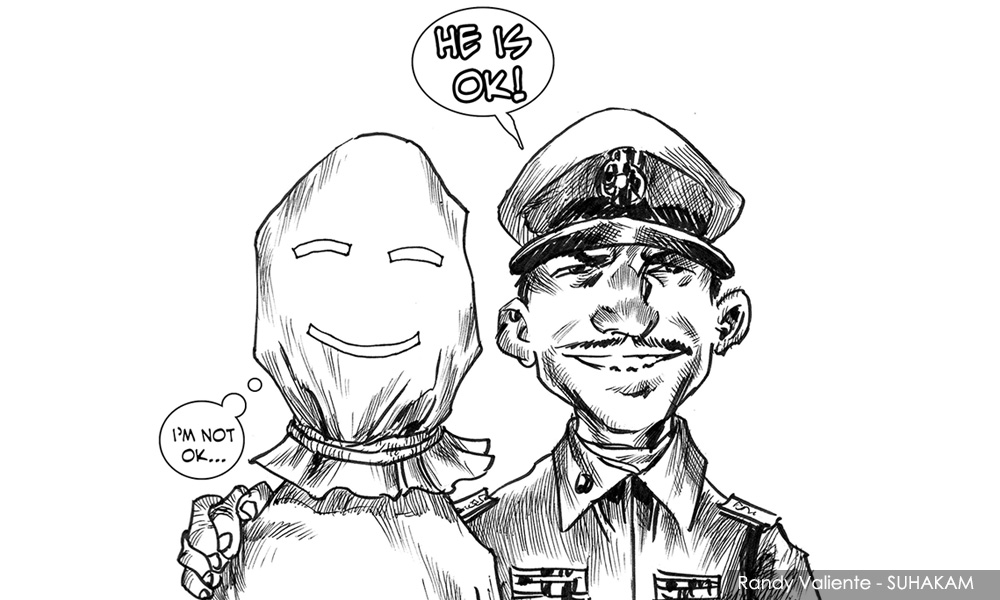

Torture, abuse and ill-treatment take place away from the public eye. It could happen to anyone. Just because an individual is arrested does not mean they are guilty of a crime. When someone is in detention, they are the responsibility of the authorities – police, prison, immigration and ultimately, the Home Ministry – all of whom have a duty to protect their charges, not mistreat them.

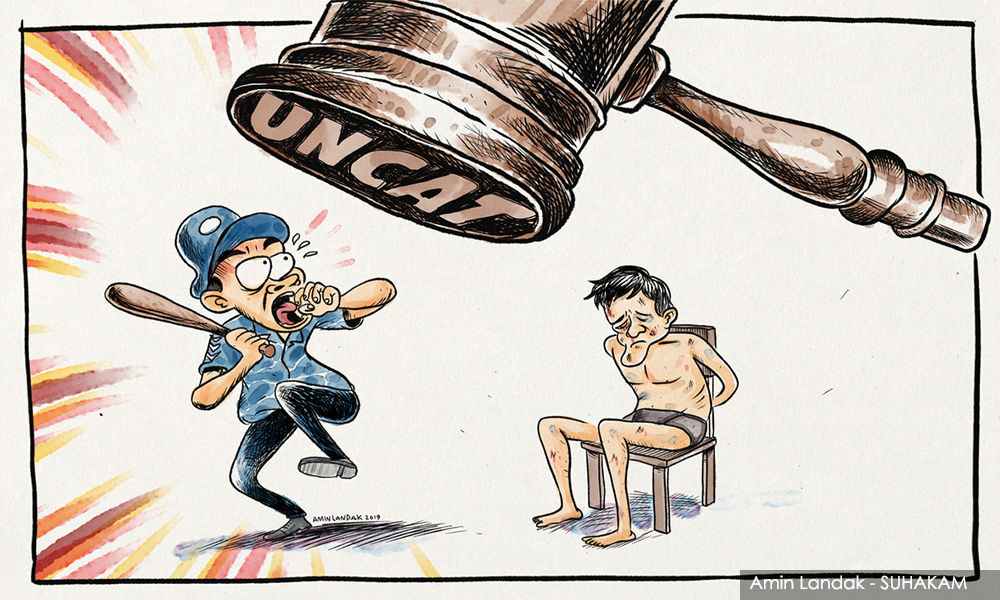

While most countries have condemned and criminalised torture, Malaysia remains one of the very few countries yet to commit to becoming a torture-free nation. This gives rise to a plethora of questions, with the most important one being, “Is Malaysia condoning torture?”

Article 1 of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Uncat) defines the term "torture" as any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person.

These acts are carried out for such purposes as obtaining from him, or a third person, information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by, or at the instigation of, or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

While there are credible mechanisms such as the Human Rights Commission (Suhakam) and the Enforcement Agency Integrity Commission (EAIC) in place to monitor the wrongdoings of the authorities, these are far from adequate in terms of resourcing, funding and the ability to prosecute.

In 2016, the EAIC had concluded that four police officers beat N Dharmendran while he was in detention and went on to fabricate evidence to cover up the act that eventually led to his death. However, the same four police officers were twice acquitted by the courts. What recourse is left for the family?

Article 4 of the Uncat says that upon ratification, each state party shall ensure that all acts of torture are offences under its criminal law.

The same shall be applied to an attempt to commit torture and to act on it by any person which constitutes complicity or participation in torture. Each state party shall also make these offences punishable by appropriate penalties which take into account their grave nature.

This goes in tandem with the government’s plan to set up the Independent Police Complaints and Misconduct Commission (IPCMC) that will allow for an independent agency to take action against members of the authority responsible for such heinous acts that violate the rights of those being investigated or those in custody. In addition, the commission will also allow for new laws to further criminalise torture.

The setting up of the IPCMC also goes well with the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (Opcat), which calls for the setting up of national oreventive mechanisms. Article 17 to 23 of Opcat further illustrate structures that will help with the setting up and establishment of the IPCMC’s operating procedures.

Amnesty International Malaysia, on behalf of the #ACT4CAT coalition, commends the statement pf the inspector-general of police in welcoming the establishment of the IPCMC to ensure a greater sense of transparency and accountability for police investigations and suspects in custody.

Malaysia is one of 28 countries that have yet to ratify and sign the Uncat. The hesitance to do so puts us among the ranks of other nations known for committing grave human rights atrocities, including China and the Central African Republic. Countries that have ratified the convention include Sierra Leone, Pakistan, Swaziland, Rwanda and Saudi Arabia.

In conjunction with the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, we stand in solidarity with individuals and families that have faced impunity and torture at the hands of law enforcers in Malaysia. It is high time for Malaysia to ratify the Uncat and the Opcat.

The current “bad rep” which international treaties have gained in the Malaysian discourse should not be a hindrance in pushing for the ratification of Uncat and the optional protocol.

The ratification of both the treaty and the optional protocol would only strengthen the government’s efforts to enhance the reputation of law enforcement agencies with a greater sense of responsibility and accountability.

It would also further secure the man on the street - that in time of police investigation or arrest, their rights will be honoured, and they will not be subjected to any form of harm or discrimination. This should be an opportunity to prove to the world that there is no place for torture, degrading and inhuman treatment of individuals in a civilised nation such as Malaysia.

SHAMINI DARSHNI KALIEMUTHU is executive director of Amnesty International Malaysia. Amnesty International Malaysia is a partner organisation with the #ACT4CAT campaign coalition, which aims to end torture and seeks the ratification of the UN Convention against Torture (Uncat) by the Malaysian government.

The National Human Rights Commission (Suhakam) will be organising a regional dialogue on the UN Convention Against Torture (Uncat) with international and regional experts on 8 July 2019 at Renaissance Hotel, Kuala Lumpur. The event, which is funded by the European Union, aims to encourage sharing of best practices among Asean and OIC member states, leading to ratification or accession including implementation of Uncat at a domestic level.

Suhakam will be conducting several closed-door meetings with Malaysian officials following the dialogue. For more information, please contact Sukhvinder Singh at 03-26125648 or via sukhvinder@suhakam.org.my. Suhakam is a partner organisation with the #ACT4CAT campaign coalition. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.