SPECIAL REPORT | “The past is the past. I don’t want to talk about it.”

This was said by former Lord President of the Supreme Court Salleh Abas in an interview with The Malaysian Insight last year when asked to comment on the 1988 judicial crisis which saw him removed as head of the judiciary in Malaysia.

The series of events was triggered by an intense fight in the 1987 Umno party election and this sparked what turned out to be the biggest judicial crisis in Malaysian history.

Although Salleh wanted to move on from the issue, the controversies that surrounded the judiciary since the crisis took place three decades ago have not abated. The latest is Court of Appeal judge Hamid Sultan Abu Backer’s revelation on judicial misconduct.

While the government has accepted the proposal of setting up a royal commission of inquiry (RCI) to probe Hamid’s claims, it is also time to remind the public that there are other unresolved issues with our judicial system.

The 1988 crisis was one of the key judicial controversies to have taken place during Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s first tenure as prime minister from 1981 to 2003. It is a case study on how executive power and the monarchy allegedly interfered with the independence of the judiciary.

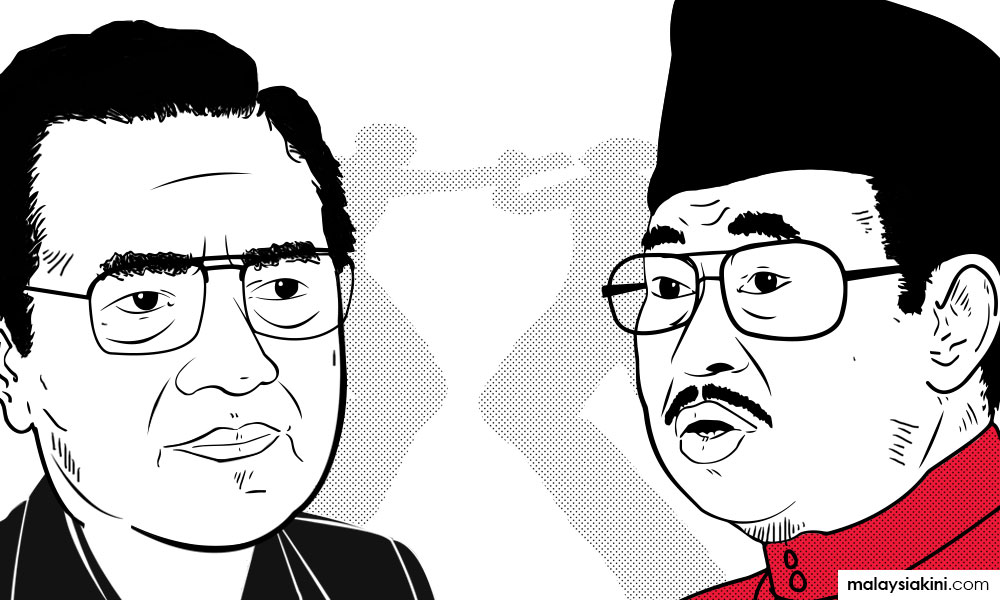

In the 1987 Umno elections, Mahathir clinched a slim victory 43 votes over Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah for the party presidency.

This result was challenged by 11 Umno members which resulted in the High Court declaring that Umno was unlawfully registered and thus an illegal organisation.

The case eventually went for appeal before the Supreme Court (now renamed Federal Court) in the following year. On June 13, 1988, Salleh was supposed to lead a full bench of nine Supreme Court judges for the hearing of the case. But this did not happen as Salleh was suspended for misconduct two days before the trial.

Let us trace back the reason why action was taken against Salleh. The Supreme Court had previously made some landmark rulings involving several cases. One of these cases was the “Berthelsen case” in 1986 where the Supreme Court overturned the government’s decision to cancel the working permit of two foreign journalists, John Berthelsen and Raphael Pura.

Following this ruling and others which the government deemed against it, Mahathir initiated constitutional amendments in Parliament in 1988. Specifically, Article 121(1) of the Federal Constitution which originally stated, “… the judicial power of the Federation shall be vested in the High Court” was amended to read that the High Court, “[...] shall have such jurisdiction and powers as may be conferred by or under federal law”.

This effectively removed the independence of the judiciary and made the courts subservient to federal laws passed by Parliament.

Six-member tribunal

To express his grievance over the government’s action, Salleh wrote to the then Yang Di-Pertuan Agong Sultan Iskandar Sultan Ismail and also the Malay rulers.

On May 27, 1988, less than three weeks before the “Umno 11” appeal was to be heard, Salleh was summoned to Mahathir’s office and was told that the then Agong wanted him to retire because of his above-mentioned letter.

Salleh refused to obey. Charged with misconduct, he was then brought before a six-member tribunal made up of high-ranking judicial officers.

On June 11, 1988, two days before the “Umno 11” hearing, the tribunal suspended Salleh. He was eventually sacked from his office on Aug 8, 1988, by the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong based on a recommendation from the tribunal.

Salleh was accused of having made statements critical of the government on several occasions, falsely claiming that the letter written to the Agong was on behalf of other judges and giving untrue information to the media that discredited the government.

Before its decision was made, Salleh did challenge the constitutionality of the tribunal and applied for an interim stay against the tribunal. But this application was denied.

However, five Supreme Court judges hearing the stay application granted Salleh an interlocutory order against the tribunal. The five judges were Wan Suleiman Pawanteh, George Seah, Eusoffe Abdoolcader, Mohd Azmi Kamaruddin and Wan Hamzah Mohamed Salleh.

This granting of the order triggered the setting-up of a second tribunal by the government to look into the conduct of the five judges who were charged with “misbehaviour”. Wan Suleiman Pawanteh and Seah were later found guilty of misconduct and the Agong ordered their dismissal. The other three judges were suspended.

The suspension of the five judges effectively suspended the Supreme Court, as told by Seah in a five-part article titled Crisis in the Judiciary published in 2004.

'Depths of despair'

“It is my considered opinion that the suspension of the five Supreme Court judges, coupled with the suspension of the incumbent Lord President, Salleh Abas — which amounted to six out of ten members or 60 percent of the Supreme Court — was tantamount to the suspension of the entire Supreme Court,” wrote Seah.

He also pointed out that the majority judgment of the second tribunal against the five judges was signed by three High Court judges who were of lower seniority.

“To use military jargon, young colonels were appointed to sit in judgment against generals. It is a very apt description of this sad episode in our judicial history. It was an episode which plunged the judiciary into depths of despair.

“I think it needs to be pointed out that there were at least 10 judges of the High Courts in Malaya and Borneo then who were more senior than the three judges sitting on the second tribunal. Ranks were ignored and apparently bypassed with scant respect for justice.

“I leave it to the general public to judge for themselves the rationale for such appointments to the second tribunal. When seniority did not count, when merit was of no consequence, what, then, was the criteria?” he asked.

The suspension of the Supreme Court meant the challenge on the legality of the first tribunal for Salleh now could not be heard.

Following the removal of Salleh, a three-man bench of the Supreme Court led by Salleh’s successor Abdul Hamid Omar heard the “Umno 11” appeal. The appeal was later dismissed.

Mahathir, meanwhile, had formed “Umno Baru” and continued his tenure as the prime minister while Razaleigh quit Umno to form Semangat 46 and went up against Mahathir's Umno Baru and BN in the subsequent two general elections in 1990 and 1995.

But Semangat 46 did poorly and eventually was dissolved in 1996. Razaleigh then rejoined Umno.

Salleh entered politics in 1995 and contested under Semangat 46's banner in the Lembah Pantai parliamentary seat. He lost to the Umno candidate.

Four years later, in the 1999 general election, Salleh stood on a PAS ticket in Terengganu and won the Jertih state seat. He was then appointed as a state executive councillor in the PAS-led government.

During his tenure as a state exco member, he revealed that following his suspension in 1988, a government official had tried to bribe him to “leave the judiciary quietly” with a lucrative job offer in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

He did not run again in the 2004 general election, reportedly due to poor health.

Subsequently, Mahathir claimed the decision to remove Salleh was made by the Agong and he merely carried out the king’s instructions. But according to Salleh, the Agong had apologised to him.* Tunku Abdul Majid Idris Iskandar, the son of the late king, also alleged that Mahathir had used his father to oust Salleh.

In 2008, then prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi announced ex gratia payments for the six judges.

However, the then BN government stressed that the payments did not represent an admission that the judges had been mistreated, but were merely pension funds for them.

(*) see: Malaysian Maverick: Mahathir Mohamad in Turbulent Times by Barry Wain

Explore the interactive story: The 1988 purge - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.