After Pakatan Harapan won the 14th general election on May 9, 2018, a palpable sense of hope filled the air.

It would seem as if the days when powerful politicians could act with impunity and when laws seemingly apply only to laypeople were coming to an end.

Anwar Ibrahim - who was at that time serving the third year of his five-year jail sentence after being convicted of sodomy a second time and jailed in February 2015 - was shown in photographs circulated on social media watching the election results with a reserved but joyful expression.

At the time, even before then-prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s full cabinet was revealed, Anwar was swiftly released from jail on May 16, 2018, courtesy of a royal pardon from the then Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the grounds that there had been a miscarriage of justice. All this happened within a week of GE14.

I too was caught in the euphoria in the aftermath of the election but Anwar’s speedy pardon stuck out to me as odd and rushed. I couldn’t shake the feeling that things had already started on the wrong foot.

Anwar and his legal team have always maintained his innocence and that the charges were trumped up to nip his then-political ambitions in the bud. They claim multiple improprieties in the investigation of the case and how the prosecution was carried out.

Their claims seemed to have at least some basis as the High Court in 2012 acquitted Anwar, with the presiding judge ruling he was not 100 percent confident that the evidence in the case had not been tampered with in any way.

However, the Court of Appeal later found the same evidence to be admissible and ruled Anwar guilty as charged, resulting in a five-year jail term. Subsequently, the Federal Court upheld the ruling.

Anwar was then jailed in 2015 and he applied for a pardon that same year, but the Pardons Board rejected his application. The PKR leader and his legal team then sought to challenge it in court.

But of course, all this became academic once he was released in 2018.

Coming home to roost

If all this seems familiar, that’s because it is. Just as Anwar’s pardon was fast-tracked in 2018, former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s pardon application was brought forward at light speed.

Presumably, in both cases, theirs took precedence over numerous other pardon applications filed well in advance.

Now, one can argue that Anwar was wronged as the High Court acquitted him but his case was then rushed through the subsequent courts. Take a look at Najib’s side and you’ll see arguments that he did not get a fair trial.

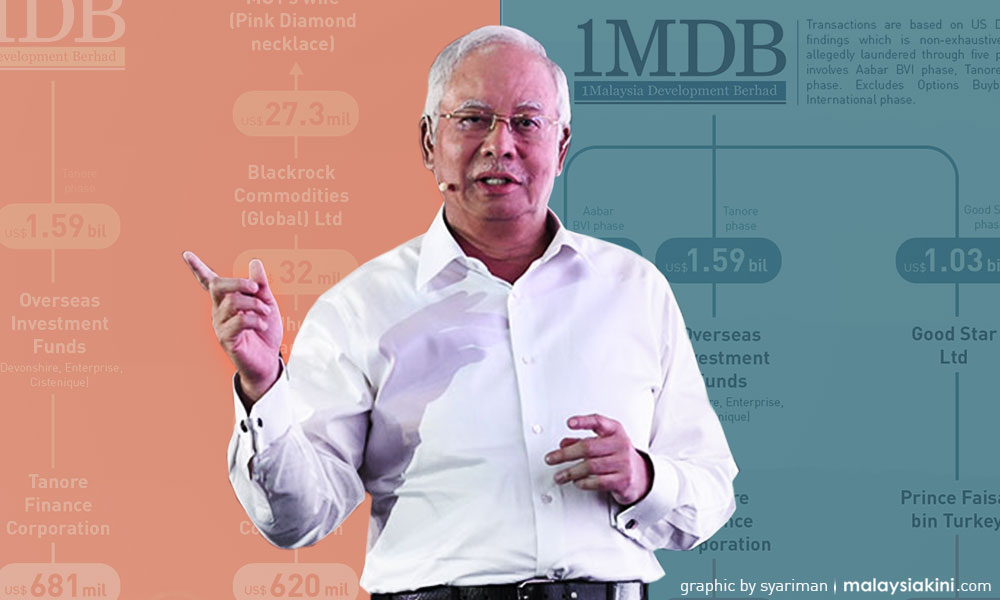

Doubtful as it may be, Najib has maintained his innocence throughout the 1MDB scandal. He and his supporters even levelled the same accusations of political persecution as Anwar did in the past.

I am not casting aspersions on Najib’s conviction by the courts, or Anwar’s for that matter. The fact of the matter is that in both cases, the courts have found them guilty of the crimes they were charged with, even if one case was seemingly more convincing than the other.

Following the reduction of Najib’s jail sentence from 12 years to six and his RM210 million fine to a mere RM50 million, Harapan leaders quickly pointed out that the Pardons Board’s decision cannot be challenged in any court. How convenient for them.

That was not what Anwar did in years past though, as pointed out above. Such justification seems nothing more than desperate damage control to appease Harapan supporters who are rightfully livid.

So, why should the preferential treatment given to Anwar in 2018 not be given to Najib as well? You cannot say the rules that did not apply to you applied to Najib.

Anwar and Harapan took the shortcut immediately when the opportunity presented itself. They can’t expect Najib and his supporters - those in positions of authority included - not to take advantage of that same opportunity as well.

Doing it right

Does that mean there is no further recourse for someone who was unjustly charged, prosecuted, and thrown in jail even though they are innocent?

While I am not aware if there are similar processes in Malaysia, perhaps we can take a page from the US.

A little context, politicians in the US have often campaigned on being “tough on crime”. Upon being elected on that promise and assuming office, the pressure is on to deliver as the American public was much less forgiving of their politicians compared to Malaysians.

This pressure extended to enforcement agencies, who were told to use all resources at their disposal to meet unrealistic targets. Finding themselves under pressure, enforcers such as the police often cut corners to achieve their objectives.

They include police brutality, withholding beneficial evidence from suspects, ignoring strong alibis, psychological manipulation, witness coaching, allowing questionable witness testimony, etc.

Although these acts were in the minority, the improprieties were widespread enough that they resulted in numerous innocents ending up with decades-long jail terms for crimes they did not commit. All so the numbers would look good for the politicians.

However, some of those unjustly imprisoned never gave up hope and kept pushing for their case to be re-investigated, evidence re-examined, testimony revisited, even if progress was slow and stretched across decades.

As the scale of police misconduct became known in recent years, many of these cases have been reopened and many resulted in complete exoneration. And all these were a matter of public record.

How does that relate to Malaysia’s predicament? Perhaps, to set a good example that the rule of law would be the new order of the day, the Harapan government post-GE14 should have ordered an independent investigation into Anwar’s case.

If any inconsistencies, improprieties, or skullduggery in the initial investigation and prosecution were found, they should then be made public through a retrial process with a presiding judge deliberating the new evidence presented in court.

Instead, Anwar and Harapan took the easy way out.

And let’s not forget that DAP leader Lim Guan Eng’s corruption case, which was already in the middle of a trial at the time, was also unceremoniously dropped in September 2018, mere months after Anwar was released.

It truly would have been more convincing for everyone involved if the trial was allowed to run its course and Lim was allowed to prove his supposed innocence in open court, with the judge granting him a full acquittal at the end of it.

With the former Penang chief minister’s case in mind, Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi’s infamous DNAA - which was also granted amid an ongoing corruption trial - should not have come as a surprise.

It’s elementary

It is often said that in politics, optics are of paramount importance. To succeed, you must not only do the work but you must also be seen doing the work.

Some may even succeed in politics by being seen to be hard at work while doing nothing, but that’s beside the point.

Harapan leaders, being career politicians, should have known better than to take the shortcuts presented to them. It left room for doubt, even among its own supporters, and a little doubt is all it takes to spoil a clean perception.

At the end of the day, if a politician is advocating against double standards, having one set of rules for the common Malaysian and seemingly no rules at all for the elites, they cannot indulge in a system they call unjust.

So, for Anwar and Lim to seemingly have taken the get-out-of-jail-free card (perceptions, perceptions), they and their supporters have now lost the moral authority to question the supposed leniency and preferential treatment given to Najib.

What leniency and preferential treatment did Najib receive if you yourself have taken advantage of this in the past? It all evens out, doesn’t it? Now, they’re all in the muck together.

Over in the US, during the height of the #MeToo movement several years ago, US talk show host Stephen Colbert made no secret of his support of it and feminism in general. But then, a senior executive of the network that carries his show was accused of sexual harassment by a junior employee.

Colbert explained on air that the executive, someone he considered a good friend, was a strong backer of the show and has protected it from blowback resulting from some of his more controversial skits. This understandably left him in an awkward situation.

Now, he could have just kept quiet about it, distanced himself, and let it all blow over like most public figures would have. Instead, after explaining his relationship with the executive, he said: “Either accountability applies to everyone, or it applies to no one.”

In Malaysia, we can only continue to dream as Harapan is not the hope it said it was. Not because they let Najib off lightly as some are accusing them of, but because they took the same easy way out.

Despite this, I believe it is still not too late for Harapan to change course and make something out of its second stint in the federal government.

It is never too late to try and do better. - Mkini

LEE CHOON FAI is a member of the Malaysiakini team.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.