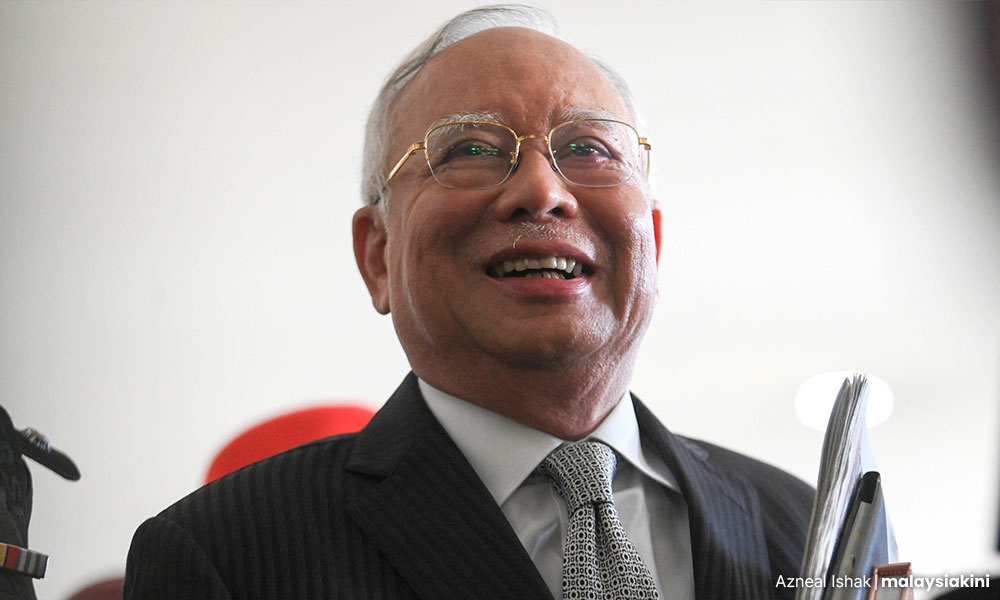

The official announcement of the halving of the jail sentence and fine reduction for convicted former prime minister Najib Razak for his first conviction related to the multi-billion 1MDB scandal shatters the trust in the Anwar Ibrahim-led government.

It is a lose-lose decision where almost no one wins, including Najib. The only winner in this decision is current Umno president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi.

In this analysis of the impact of the decision, I argue that the damage goes well beyond individuals, as the partial pardon weakens political institutions and exposes governance weaknesses.

Rather than be a supposed ‘compromise’, the decision is corrosive to the fabric of Malaysian democracy.

An unsatisfactory deal

Yesterday’s decision was no surprise. For months – especially after the Anwar-led government granted a DNAA to Deputy Prime Minister Zahid for his scores of corruption charges last August – it was clear that something unpardonable was afoot.

The partial pardon decision showcases the central role of political deals in shoring up the current government. The coalition government rests its power not on a clear electoral mandate, as no coalition won a majority.

It is a post-election agreement among elites, leaders of different political parties. Umno leaders have used the circumstances to their advantage. Its president Zahid has secured the removal of his corruption charges. Najib has secured a reduction in his first conviction.

Najib has not won a real victory; at best it is a partial one, as his daughter’s response highlights. Najib remains in jail, despite the hopes of his supporters.

Najib has been increasingly portrayed as the person who can save Umno. His popularity has increased as dissatisfaction with Zahid’s leadership of the party and public disappointment with the Anwar government have grown amid persistent difficult economic conditions.

The status quo of Umno – publicly weak but its core leader politically essential for the government – remains.

With no Najib release, Zahid’s position as Umno president remains secure. He is the only clear winner of the partial pardon decision. He can claim some leniency was gained through pressure, but does not have to fear displacement - at least for now.

For Anwar, as a struggling prime minister, he also does not have to face a free Najib wildcard, as the former prime minister’s popularity, particularly among his base of Malays, would challenge his own.

Not a real compromise

While he has strengthened his key ally, Zahid, Anwar has weakened his ties with other parties in Pakatan Harapan who have been forced to accept the partial pardon decision.

When one is forced to accept, this is not a genuine compromise. As with the DNAA decision, Umno was given priority over other parties in the government.

While this decision was not just cavalierly announced, instead it was a sword hung over the heads of political allies through leaks and build-up so that it seemed a better alternative than a full pardon.

The partial pardon cuts all the same. Harapan partners are supposed to be relieved and pleased that the ‘worst’ (a full pardon) did not happen.

In the silence of key Harapan allies in the partial pardon accommodating Umno, there is dismay within the government, including within Anwar’s own party. Trust among coalition partners is being affected, as is the trust in Anwar’s leadership.

The burn runs deep. It is not only a matter of the decision itself but how the decision was made, without meaningful consideration of the political implications for parties that rested their legitimacy on reforms and pushed for political accountability on the 1MDB scandal, notably DAP and Amanah.

Angry public outcry

The most trust affected is that of the public, however.

The 1MDB scandal divided Malaysia politically as it tipped the balance of electoral power away from Umno in 2018, and arguably in 2022 as corruption continued to be decisive in that election, with support moving to Perikatan Nasional’s leadership for putting Najib in jail.

Ironically, the Anwar government’s partial pardon decision brings different sides together in their dissatisfaction. Najib supporters are deeply disappointed. Harapan supporters are angry. Those disengaging from politics are increasingly cynical. Too many Malaysians are losing hope in their leaders.

This decision does little to heal Malaysia’s political divides, rather it reinforces them. The reasons are clear: There was no remorse on the part of Najib for his crimes. There was no transparency on the grounds of the partial pardon decision.

Malaysians are asking why the fine was reduced, especially when outstanding taxes due by Najib have yet to be paid. There was even less transparency on the process involved, with all of those involved in the decision not disclosed. There remains a lack of clarity on Najib’s ability to claim other pardons.

The delays in announcing the pardon decision of significant public interest showed a lack of respect, even disdain, of the public, the same public who are paying for the 1MDB scandal and, in fact, are being asked to pay more taxes in March’s tax increase.

The partial pardon decision reinforces the growing resentment of elites using power to serve themselves while ordinary taxpayers have to pay the price.

As grating has been the attempt to deflect responsibility for the decision after the fact. Anwar blamed the Agong in an interview with international media, while Pardons Board member and close Anwar-family ally Federal Territories Minister Zaliha Mustafa claimed ‘collective responsibility’.

Other politicians are not speaking at all, shamefully trying to ride out the storm.

Damage done

Despite deflection attempts, the damage to the Anwar government is real. While reform has not made any substantive gains during his tenure, this decision erodes already low credibility and confidence. It makes the task of governing and bringing about needed structural changes all that more difficult.

For many Harapan voters, the decision marks the end of their reformasi dream, a dream that has been fading under the Anwar-led government. The obstacles to improving governance – especially on corruption - have become higher, as the attractiveness for non-corruption tied investment has dropped.

With one partial pardon, Malaysia’s economic competitiveness in an increasingly more competitive region has declined.

Internationally, few understand why the senior person tied to the largest kleptocracy scandal in history has been given leniency, even before his ongoing trials are over. The decision reinforces the view that there is a lack of a moral compass globally.

Rather than Malaysia taking the lead in anti-corruption and better governance, as election results reinforced and Anwar’s leadership claimed, it has joined the morality malaise.

Domestically, the impact on political institutions is just as serious. The decision affects the legacy of the past Agong and feeds perceptions of the royalty. The decision raises questions about the powers of the attorney-general, as has been the case in recent politically charged cases.

The effects on the rule of law on matters of corruption and perceptions about the rule of law are deeply concerning. Rather than strengthening the judiciary and executive, the decision does the opposite.

As long has been the case in Malaysia, the politicisation of legal decisions has weakened the institutions involved.

Some argue the partial pardon decision strengthens Anwar, making his government more secure in a ‘compromise’. This is a short-term misreading.

Trust among the public and allies has been affected. Good governance will be harder. Dissatisfaction, anger, and cynicism have grown, and while some emotions will dissipate, many will remain.

Sadly, from a lack of remorse for crimes, to the deal-making, and an unwillingness to accept responsibility, this decision illustrates the failings of political leadership.

The partial pardon decision is a poison pill that Malaysians will have to swallow. It is not likely to kill outright, but it adds unnecessary toxicity to an already fraying politics. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honourary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.