Malaysia marks her 61 years as a nation today. There is so much to celebrate and be proud of. Five generations from the boomers to alpha Malaysians have achieved something that is truly special.

There is nowhere in the world that rivals the collective multiethnic blend of cultures and communities that comprise this great, beautiful nation.

An integral part of this beauty has been her greatest asset - her people - resolutely striving for their dreams. As she continues her sixth decade, Malaysia continues to bravely face its challenges head-on.

One of those challenges is the very different notions of what the nation should be. Malaysia may be one country, but how her citizens conceive her is not the same. There are significant differences among Malaysians over the legal source of rights, who should hold power and have rights, and the goals of nation-building itself.

Unlike in the past when there were more shared ideas over Malaysia, different views of nationalism have become more entrenched. These divisions feed into the political polarisation evident in elections and contribute to the increasingly contentious political discourse. There is a need to unpack these differences with the aim of promoting dialogue to find common ground.

Drawing from discussions with Malaysians over the years, this piece shares my interpretation of five different contemporary visions of Malaysia as a nation. The differences are presented starkly, to highlight the variation. In practice, there is more overlap and ambiguity than is presented.

Vision 1: One multicultural Malaysia

This idea of Malaysia may be the most familiar to liberal readers. It has underscored political mobilisation over the last few decades fighting for rights, the conception that all citizens in Malaysia have rights and these come from the 1957 Federal Constitution.

Drawing from a Westminster tradition and Western notions of rights, power rests with elected representatives through regular elections, with a constitutional royalty with limited powers.

Ordinary citizens exercise power through voting and have protections embodied in the Constitution, and while rights may not be equal due to provisions in the Constitution, differences are resolved through dialogue, legal cases and, when necessary, political compromises.

Of all the visions for the country, this one is the most democratic and inclusive.

Vision 2: Malay Malaysia

Malaysia’s politics has long been tied to Malay nationalism, and it is this idea of Malay empowerment vis-à-vis the other communities, especially Chinese Malaysians, which comprises a second notion of Malaysia.

While tied to the negotiations for independence in Malaya and integrated into political compromises in the 1957 Constitution, the ideas were institutionalised after the 1969 racial riots and resulting compact, which created an ethnicised hierarchy of rights, evident in policies such as the New Economic Policy.

It has evolved into the idea of Ketuanan Melayu with its pre-eminent and special position of the Malay community, and in recent years deepened to evolve into a more exclusionary ultra-Malay ethnonationalism.

At its core, a Malay Malaysia has been about Malay empowerment, a country led by Malays for Malays. More recently, it has taken on more anti-Western discourse, forged Malay identity with religion and become more assertive in undercutting the rights of minority communities.

While tapping into ethnic insecurities, this vision is rooted in the betterment of the Malay community who make up the majority of the country and holds that the main democratic struggle is about the contest among Malay leaders and political parties for Malay leadership.

Vision 3: Islamist Malaysia

Few appreciate that the idea of an Islamist Malaysia - a third vision of Malaysia as a nation - is also historically rooted in the struggle with the colonial powers and among elites over a century ago. Malaysia has a rich Islamic heritage and debate among Islamic scholars. For many decades this struggle took place within the Islamist party PAS, which moved from a more inclusionary notion of nationhood to a more exclusionary one.

A pivotal turning point was after PAS left the BN coalition in the 1977 Kelantan Emergency and then adopted a more conservative brand of political Islam in the 1980s, prioritising the role of religious ulama in political leadership.

Rather than draw from the 1957 Constitution, political legitimacy became seen through a religious lens, through the interpretations of religious documents. While the Constitution is not rejected, it is not seen in the same way as other perspectives.

As with Malay nationalism, there is a parallel hierarchy of rights, with non-Muslims not being part of the same community and deep suspicions about non-Muslim leadership and alliances.

The focus of many of the Islamist Malaysia proponents - which extends beyond PAS and religious officials in institutions - is on bringing about an Islamist nation, with different ideas on what this means.

For the more conservative Muslim leaders, such as PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang, this involves the imposition of syariah law and social controls and a clear secondary status of non-Muslims. As with the other contending ideas, the ideas are evolving, with the power of the ulama in PAS declining, for example, while the ideological coherence of Muslim predominance and empowerment is increasing in strength.

Vision 4: Borneo Malaysia

The mobilisation around MA63 in Sabah and Sarawak and calls for greater autonomy and financial balancing of resources speak to yet another vision of Malaysia, one in which Borneo wins greater autonomy and control over its own destiny.

After years of neglect and exploitation of its oil and gas reserves by elites in Peninsular Malaysia and comparative impoverishment, Borneo leaders have pushed hard for greater representation and powers, as evidenced by the negotiation results this past week.

This mobilisation around Borneo nationalism has intensified in the last decade, beginning with the leadership of Sarawak’s Adenan Satem in 2014.

The views of what Borneo nationalism and empowerment mean vary, especially in Sarawak compared to Sabah. While more democratic, Sabah grapples with a legacy of Umno’s intervention, greater political fragmentation and a serious problem of over one million undocumented persons tied to political manipulation and contemporary leadership cowardice in reaching a resolution.

Many in both Sabah and Sarawak want full independence, even separation, especially in Sarawak, and have ratcheted up demands, not least of which involve unresolved levels of representation in national legislatures.

As with other ideas of the Malaysia nation, there is a hierarchy of rights of communities even within Borneo itself, tied to different views of equality and justice. Legally, the focus is on the MA63 agreement rather than the 1957 Constitution, but discussions of rights are evolving as the mobilisation is deepening.

What has happened, however, is a growing divide between Borneo and “Malaya” - used negatively to demark others while at the same time adopted as part of the Borneo empowerment drive.

Vision 5: Malaysia is mine

Leaders across political spectrums may differ over how they see Malaysia as a nation, but there is a common thread among political elites. Too many of Malaysia’s leaders believe in a sense of their entitlement, not just to political power but also to her economic resources.

The nation is something to be captured and exploited for personal gain, to make money at the expense of more inclusive governance.

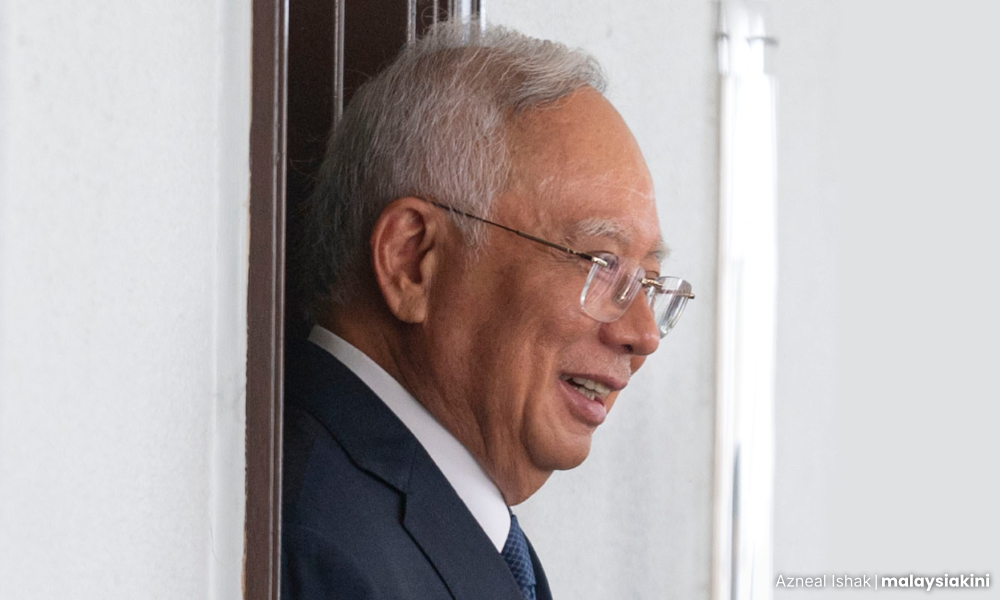

This was brought home in the 1MDB scandal where former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s greed was on display. Yet the practices of deal-making by using positions of power, connected cartels controlling sectors of the economy, and corruption continue to be inadequately checked. Politically aligned greed is ever present in governance, with its own hierarchy regarding rights and representation.

Long-standing notions of feudal power remain entrenched, where Malaysia is a nation for the elites to sustain their own power and the interests and welfare of ordinary citizens are often secondary concerns. People are expected to just accept the misuse of power. This is arguably the most narrow and exclusionary vision of Malaysia.

Navigating notions of a nation

These five notions of what Malaysia as a nation coexist, are changing and can often blur into each other. Elites in Sabah and Sarawak, for example, can adopt similar patterns of elite entitlement as those in Peninsular Malaysia.

Malay nationalism and Islamist discourse similarly extend across the South China Sea. Liberal notions are shown to be limited when supposed liberal leaders adopt Islamist narratives to seek political legitimacy or undercut civil liberties.

Navigating different notions of nationhood is not easy and has become even harder to manage. Righteousness and anger are increasingly shaping ideas by political elites who often use the various nationalistic narratives to suit themselves rather than Malaysia as a whole.

Society has been battered, with the spirit of compromise and tolerance less evident than in the past, and the realities of injustice and weak governance ever present.

The need for statesmanship as opposed to nationalistic brinkmanship, for understanding and empathy rather than posturing and indifference, is more pressing than ever.

It is well beyond time to move away from politics that fuels division and move to strengthen shared institutions and build common ground across communities. It won’t be easy, but Malaysia has shown that in tackling her challenges she has prospered and persevered.

On this day that recognises Malaysia in all her splendid glory, Malaysia Day, it is vital to appreciate that adept management of these differences is what has been her strength historically, along with an embrace and respect for diversity.

Today’s leaders need to do more, much more, to unify the country and protect harmony among communities, to create conditions where all Malaysians feel a genuine sense of celebration. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honourary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.