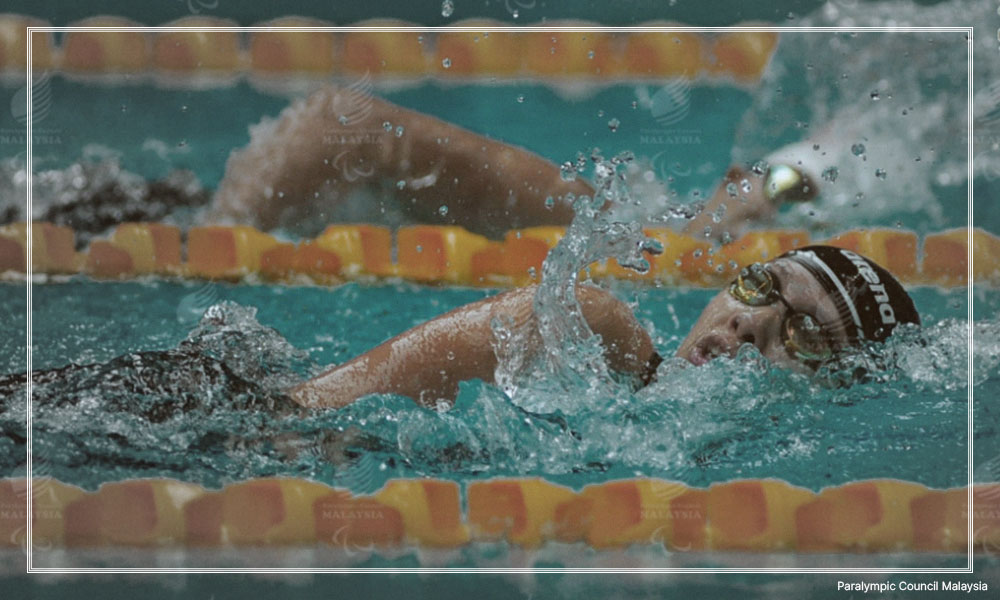

MALAYSIANSKINI | With just her right arm, Carmen Lim has been beating the best para swimmers in Southeast Asia for the 50m freestyle (S8) since she was 15 years old but being a professional swimmer was never really in her plans.

For much of her life, the 2024 Paris Paralympic hopeful had wanted to be a lawyer.

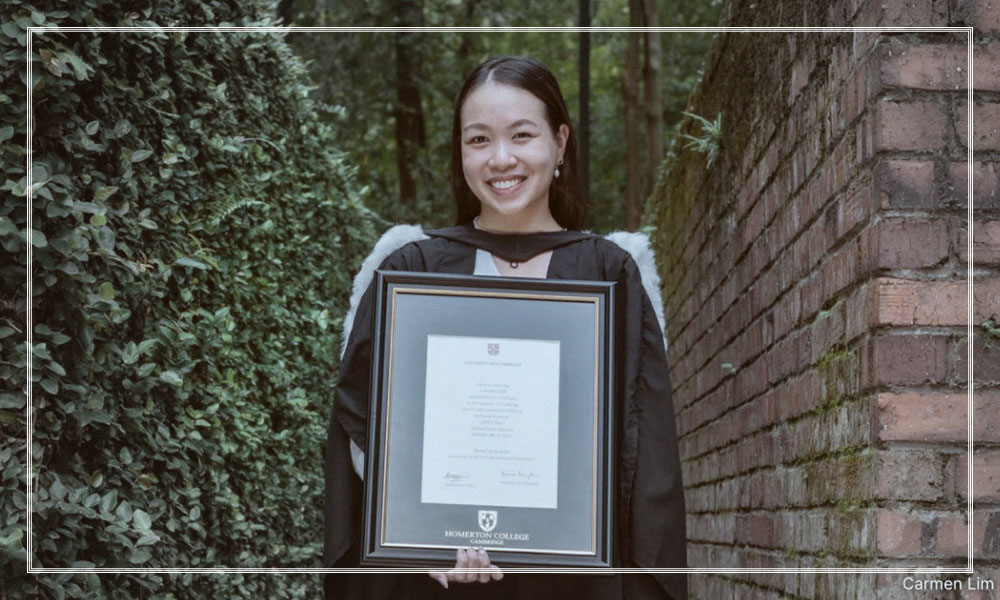

Today, defying all odds, she has achieved both - ranking among the top para swimmers in the region and graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in Law from the University of Cambridge.

“I never really thought about swimming as a professional career before because my family always focused on my education, and swimming was seen as an extracurricular activity to them,” said Carmen, who bagged three gold medals and one bronze in the 2023 Asean Para Games in Cambodia.

And yet, the Subang Jaya native had the honour of holding the record for the 50m freestyle category for almost a decade.

Even more remarkably, since setting the new record in 2015, she has beaten herself twice - at the Asean Para Games in 2017 and again at the same games in 2023, clocking her best time of 34.43 seconds.

In para-sports, there are different categories based on disabilities so competitors within each category have similar disabilities to create a level playing field.

Despite being born without her left arm, Lim said she has never felt like she was missing anything. Much of this, she said, was thanks to her parents who didn’t treat her differently.

“It may not be natural to others because they think of themselves with both arms moving.

“My movements now are the most natural to me. I can’t imagine what it's like to have a left arm.

“If you ask me to imagine myself with a left arm, I think of dead weight. I don’t think of it as being able to move a left arm,” the 24-year-old said.

Surprise success

Her latest success was a surprise even to Lim who only returned to professional training 10 months prior after taking time off to complete her degree and only swimming part-time.

“I started training full-time in December 2022 and competing in March 2023 after the Covid-19 pandemic-related restrictions were lifted and I knew I was far from the Paralympic qualification standards, initially.

“I didn’t think Paris was even a possibility when I returned to professional swimming after such a long break, but surprisingly I saw significant improvements and I was swimming better than ever before, not just in the 50m freestyle but in all events.

“I was clocking good timings and I earned a spot in the World Championships, which gave me a chance to qualify for the Paralympics,” she said.

Her success in 2022 won her the national title of Paralympic Sportswoman of The Year, and her hard work placed her 19th in the world for her specialised swimming stroke in the 2023 season.

Lim now also trains in 100m backstroke and 100m breaststroke.

Her recent success has changed how she sees swimming. These days, she said, it is a professional venture and not just something she did on the side.

“Despite my salary not reflecting that,” she quipped.

“Now that I have completed my degree and my education goals, I have the freedom to make my own decisions about my career path, including pursuing swimming full-time for at least another two years,” she added.

Strong support system

Lim can’t say for sure why she was more inclined towards swimming but some physical dispositions made other sports, like athletics, less favourable.

Since childhood, a condition of low haemoglobin levels meant she was more prone to fainting.

“So swimming seemed a more suitable option given the circumstances,” she said.

Excelling at this extracurricular activity, she started training for professional meets at the tender age of 13.

But at 14, she hit turbulent waters when she lost her mother, Angie Ng, who died of a heart ailment at 49.

Her mother was Lim’s biggest champion and was the one who first enrolled her to swim with able-bodied swimmers as a child.

Looking back at those troubled times, Lim said, her businessperson father Chee Kiong, aunt and the entire extended family’s unwavering support served as her anchor.

“I often say that it takes a village because pursuing a sporting career can feel lonely since not many people do it.

“My family came together to support me in my swimming and my studies despite the grief of losing my mum, ensuring it didn't hinder my potential,” said Lim, who is an only child.

She also credits her coaches, including Loke Chee Heng and Yong Huey Ying, who started coaching her when she was a schoolgirl in Sri Kuala Lumpur, and who remain her coaches to this day.

“(They) were always supportive and never treated my disability as an issue.”

Lim shortly parted ways with her coaches when she left the country to do her A Levels at a boarding school in North Wales, before winning a spot at the prestigious Cambridge University as a Khazanah scholar.

She kept excelling in swimming during her university years. Not only did she serve as co-president of the Cambridge University Swimming and Water Polo Club, but she also earned the prestigious accolades of Full Blue and Extraordinary Blue in 2022, the university’s highest honours for athletes.

Competing in various meets, from the historic varsity showdown against Oxford to national inter-university competitions, her achievements bolstered her team’s overall standing.

Privilege and responsibility

Talking about her journey, Lim was quick to note her schooling life and experience as a young athlete differed from many para-athletes and disabled people, who face a multitude of obstacles.

“Being part of my school swim team, training alongside my friends and classmates, made me feel like any other student,” she said.

It is this acute realisation of her privilege that drives Lim to advocate for other athletes, including as chairperson of the athlete council in the Paralympic Council of Malaysia.

This is especially because, unlike other athletes, she has her legal career to fall back on if things don’t work out in the sporting arena, Lim said.

“It’s not about condemning the government or sports bodies, but my privilege lets me advocate freely for para-athletes because I have less to lose.”

Although she has not faced difficulties, she believes it is important for the higher authorities in the council to address concerns raised by para-athletes.

The most pressing issue revolves around the uncertainty over who will represent Malaysia at the Paris Paralympics from Aug 28 to Sept 8.

The indecision puts athletes in a tricky situation because they need sufficient time to plan and prepare, she said.

Although Lim has qualified to compete in the World Series, which leads to Paralympic qualification, she is uncertain if she will be part of the national contingent heading to Paris.

“There might be a plan but time is running out because planning and preparation don’t happen over a month or just weeks.

“Preferably athletes need a year and not having that time is not ideal.

“I’m sure the Paralympic Council and the National Sports Council are trying to finalise this,” she said optimistically.

Life after sports

Another matter close to her heart is helping para-athletes prepare for a productive and fulfilling life after retirement from sports.

“This is not a concern for para-athletes only. It affects national athletes too and many have dedicated their lives to sports from a young age, sometimes inadvertently neglecting education.

“Retirement from sports can come early for many because not everyone can be like (motorsports race driver) Fernando Alonso who continues to compete at 42 years old,” she stressed.

This is especially important for para-athletes, she said, because people with disabilities face discrimination from a young age, leading to fewer opportunities in life.

Even with her privileges, Lim, too, has faced discrimination in the job market.

Once, when submitting an online job application, she found she could not even send it through without first ticking a box stating she was not disabled.

But her status as a disabled person was apparent in her application because she had declared that she was a para-athlete. The company ultimately rejected her application, although the reasons are unclear.

Policy changes have improved conditions for sporting professionals, with athletes in the podium programme now offered two-term contracts, and receiving Employees Provident Fund and Social Security Organisation contributions.

But more can be done to help athletes prepare for what comes after the curtain falls on their sporting life, she said, and this needs a culture shift among coaches, support staff and management.

It involves considering the holistic development of athletes, even if it means the athletes may miss a few training sessions to pursue other interests, she added.

Cultural change

The cultural change she advocates is to balance an athlete’s development with their academic pursuits.

“Other countries have successfully demonstrated that it was possible to nurture both aspects simultaneously.

“In the UK, universities often emphasise sports alongside academics, with some specialising in their sports facilities, their training and their coaches,” she said.

Having won her spot at Cambridge University on academic merit, she said her experience proved both sports and academics can go in tandem.

“I went to an academic university which prioritises academic achievements and my sporting career played no part in my admission into Cambridge.

“Yet, I was able to swim with the university team for three years and compete in national competitions in the UK because there are many large-scale inter-university meets.

“The universities give importance to these competitions and students, despite their demanding academia, are given the opportunity to excel in sports,” she said, adding that students had options and were not limited to one or the other.

Crucially, preparing athletes in Malaysia for life after sports must go beyond just making them attend seminars and talks, she said.

“This culture shift needs to come from within the coaching and management teams for the message to reach the target audience better.

“We need more open casual conversations with athletes and it should happen as regularly as daily, during breaks, for example,” she added.

Ending on a high note

Lim’s career plans are clear in her mind.

She has set her retirement date for 2026, making the Paris games this year her last chance at clinching a Paralympic medal before she shifts focus to soaring as a legal eagle.

She also hopes to end her tremendous swimming career on a high note, at the winner’s podium of the Asean Para Games in January 2026.

Despite her impressive accomplishments, Lim remains humble and approachable.

She quipped that describing her swimming journey as a metaphor for life might be romanticising hardship, but readily acknowledges how it has helped her become a stronger person.

“Swimming has taught me resilience.

“I remind myself that the real magic happens when I tackle the hard stuff instead of avoiding it.

“It’s the perseverance during those difficult moments that get you to where you want to be.”

MALAYSIANSKINI is a series on Malaysians you should know.

In March, we will be featuring notable Malaysian women as part of the Women In Front series for International Women’s Day.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.