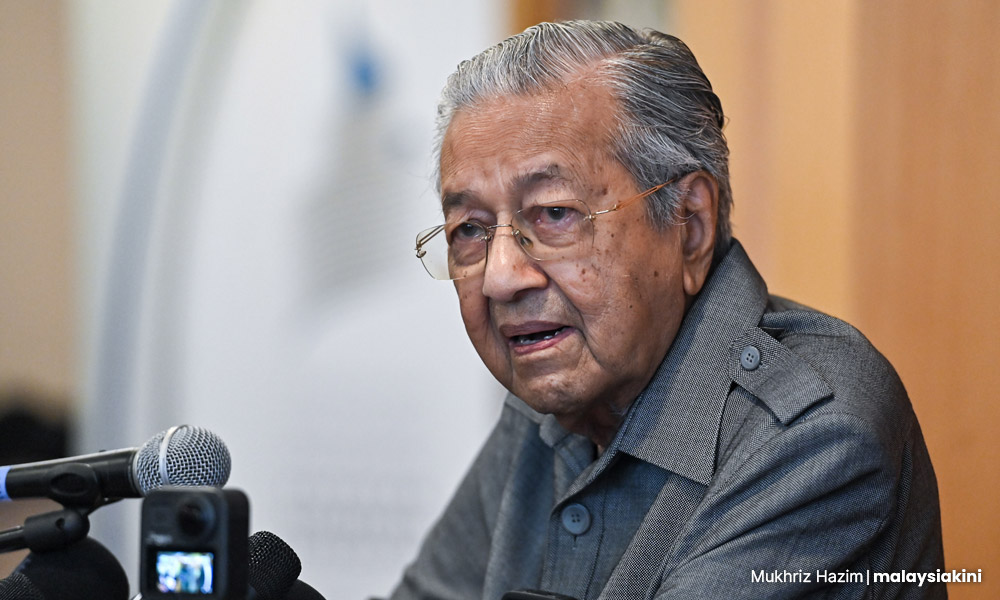

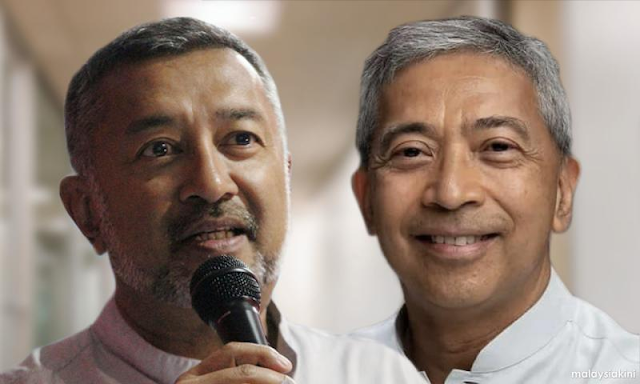

KINIGUIDE | Two of former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s children, Mirzan and Mokhzani, are under investigation by the MACC and have been ordered to declare their assets.

Both were known to be active in the business world and are reputed to have immense wealth. But how did they get there, and exactly how wealthy are they?

In this instalment of KiniGuide, we revisit what is publicly known about their wealth and the controversies along the way.

Who are Mirzan and Mokhzani?

Mahathir and his wife Dr Siti Hasmah have four biological children; Mirzan and Mokhzani are their second and third children, respectively, with Marina being the eldest and Mukhriz being the youngest of the four.

The couple also have three adopted children: Melinda, Mazhar, and Maizura.

According to Bloomberg and the University of Pennsylvania’s alumni webpage, Mirzan used to work for the US-based investment bank Salomon Brothers and is currently the founder and chief executive officer of the Malaysian investment holding and financial advisory firm Crescent Capital Sdn Bhd.

He holds directorships in several public and private companies in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines’ largest oil refiner Petron and the local electronics manufacturer Betamek. He is also the former CEO of Konsortium Logistics Berhad (KLB).

Meanwhile, Forbes has listed Mokhzani as among Malaysia’s richest persons several times since 2007. Forbes ranked him as the ninth richest in Malaysia in 2013, with a wealth of over RM4.22 billion from the oil and gas industry.

He founded the oil equipment fabricator Kencana Petroleum, which later became SapuraKencana Petroleum following its merger with SapuraCrest in 2012 and is now known as Sapura Energy.

Mokhzani had reportedly relinquished his stake in SapuraKencana in late-2017.

What was Mirzan up to?

In the 1990s, Asiaweek valued Mirzan’s holdings in public companies alone at over US$880 million.

His first big break in Malaysia, after returning from the US, was in KLB’s predecessor Konsortium Perkapalan Berhad (KPB).

According to KLB’s 1999 annual statement, Mirzan managed to increase KLB’s turnover from RM100 million in 1995 to RM417 million in 1996, more than quadrupling its turnover in just one year. It reached RM730 million at its peak in 1997, attracting attention from both domestic and international markets.

Unfortunately, the company’s aggressive acquisitions and expansion placed it under significant debt pressure, and it was hit hard by the sudden onset of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Its liabilities grew to RM400 million.

As part of an ongoing lawsuit, the finance minister at the time, Anwar Ibrahim, claimed Mahathir had tried to rescue several financially distressed companies amid the crisis, including KPB.

Mahathir supposedly became upset when Anwar refused and was concerned about potential embarrassment if the matter was presented in Parliament for debate.

So instead, Mahathir allegedly sidestepped Anwar’s authority by ordering Petronas to rescue KPB since the oil company came under his purview as the prime minister.

The Petronas subsidiary MISC Bhd bought over KPB for US$220 million.

In his autobiography ‘A Doctor in the House’, Mahathir defended the move, saying it was not a bailout because Petronas bought KPB at a low price and sold some freighters at a handsome profit when the shipping industry recovered.

Mirzan would remain as KLB’s executive chairperson until his departure in August 2007, while the company evolved to become known as Pos Logistic Bhd today.

What about Mokhzani?

Former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak had claimed that Mokhzani’s Kenchana Petroleum won a license to fabricate offshore structures from Petronas in 2002.

The allegation was made in 2020 in response to Mahathir’s assertion that Najib’s children benefited from government contracts during his premiership.

In turn, Mokhzani also denied Najib’s claims saying that Sapura Kencana Petroleum was only established in 2012, after Mahathir had already stepped down from his first stint as prime minister.

Nonetheless, evidence from Kencana’s 2011 annual statement confirms that Kencana Petroleum Bhd, before its merger and renaming, had indeed secured a Petronas contract in 2002 as Najib claimed.

Mokhzani also once headed the fibre optics manufacturer Opcom Group founded by his brother Mukhriz.

In a lawsuit, Anwar claimed Mohkzani, Mirzan, Mukhriz, and Mukhriz’s wife Norzieta Zakaria were directors of the company from 1994 to 2021.

He claimed that during this period, Mahathir had used his position as prime minister and finance minister to influence Telekom Malaysia (TM)’s decisions, which carried out direct negotiations with Opcom for the supply of fibre optic cables.

Opcom had also raised eyebrows after being awarded a RM11.16 million contract from TM just days after the 14th general election and Mahathir’s swearing-in as prime minister under the Pakatan Harapan coalition.

TM later clarified the decision was made before the election following an open tender process.

Later when the National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan was announced in 2019, Opcom share prices spiked amid speculation that it would become the main beneficiary of the project.

The communications and multimedia minister at the time Gobind Singh Deo subsequently clarified that Opcom couldn’t have bid for the contract because it didn’t have the relevant license.

What does Mahathir have to say?

Mahathir has long asserted that his children’s wealth was due to their own hard work and had nothing to do with him.

“If they are rich now, it is through their own efforts.

“They are entitled to be rich, that is if they can become rich. But some of my relatives are as poor as a church mouse,” he reportedly said in 2018.

During a 1998 interview with Asiaweek, he responded to allegations of nepotism and cronyism by saying the government must assist the private sector, especially bumiputera-owned companies, to correct economic imbalances.

He challenged the interviewer to “Tell me any single businessman who is not close to this government”.

In the lawsuit with Anwar, Mahathir accused his former protégé of being a pathological liar who never showed evidence for his allegations of abuse of power.

He pointed out that Anwar himself told the media in March 1998 that MISC’s purchase of KPB was not a bailout but a business decision.

He also countered that Opcom was far ahead of its competitors as a pioneer in supplying fibre optic cables in Malaysia, with various ISO certifications to show for it.

Even Anwar had conceded that TM itself issued a letter to the Finance Ministry to hold direct negotiation with Opcom over the fibre optic contract, Mahathir noted.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.