The MIC is facing one of its biggest challenges since its formation.

Developments involving the BN component member remain fluid, from leaders and members quitting the party to it skipping the upcoming six state elections.

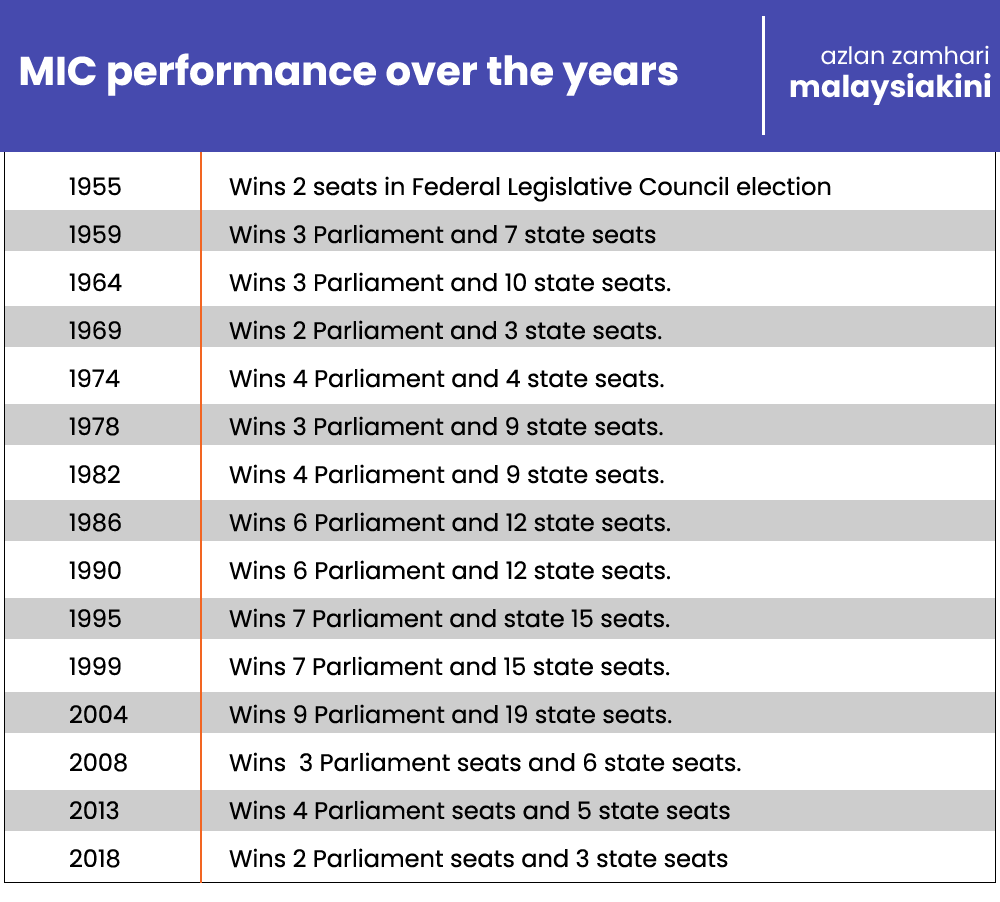

These political developments, especially not contesting the polls have placed MIC on unfamiliar grounds as the party has never skipped any elections - be it for the state or parliamentary seats since first taking part in the 1955 federal legislative assembly election.

MIC president SA Vigneswaran revealed that one of the primary reasons his party and MCA in skipping the six state elections was that they were sidelined in seat negotiations.

While some welcomed the move as a sign of protest against the BN, others criticised it as a betrayal of the voters and the Indian community.

The MIC’s decision not to contest may have temporarily saved its dignity and reputation.

Party secretary-general RT Rajasekaran said the decision not to contest in the state elections is to protect the party’s interests.

He said at the same time, MIC will focus on strengthening the party to face the 16th general election.

In skipping the polls, will MIC utilise the time to revitalise and rejuvenate the party? What will it do? How will MIC do it?

Only second to Umno in its age, the party was formed in 1946 by well-minded community leaders with the aim of uplifting the Indian community in then-British Malaya and in post-independent Malaya.

After gaining independence in 1957, the MIC, modelled after India’s Indian National Congress, became a prominent political party within the ruling coalition, the Alliance Party, which later evolved into the BN.

The MIC was successful in securing parliamentary and state seats as well as holding ministerial positions and state executive positions in successive elections.

It had illustrious leaders helming the party, such as VT Sambanthan, V Manickavasagam, and S Samy Vellu, who played influential roles in Malaysian politics.

Hindraf rally

Despite MIC’s past success and achievements, it is anything but that nowadays, and a former shadow of itself.

The largest Indian ethnic party outside the Indian subcontinent, which held sway for over six decades since its 1955 outing, has seen its political and electoral fortunes begin to slide, specifically after its dismal performance in the 12th general election (GE12) in 2008.

Just a term before, in the 2004 general election (GE11), the MIC carried nine parliamentary and 19 state seats. It was one of the best performances for the party.

Yet just four years later, things turned sour. The GE12 saw it only win three parliamentary seats and six state seats. The status quo remained in 2013, with it winning four parliamentary and five state seats.

However, from then on, it saw the seven-decade-old party slowly but drastically losing ground in the electoral field.

In 2018, it won only two parliamentary seats and three state seats, whereas, in the 2022 general election, its parliamentary seat dropped to one.

The catalyst that kicked off its string of poor showings was attributed to the Hindraf rally in November 2007. The movement came to the fore as the Indian community felt that the MIC forgot its role and did not effectively address the issues and concerns of the community, unlike in its initial years.

This, in turn, led to disillusionment against the party and a decline in support from the Indian community.

With the support from the minority Indian voters also being courted by multiracial parties such as Gerakan, DAP and PPP, the MIC’s support base continued to erode.

Yet the erosion of MIC’s influence among the Indian community and voters at large was already in play years before the Hindraf rally. Internal leadership disputes and other internal divisions over the preceding years also saw the MIC’s structural cohesion and effectiveness being undermined.

A classic example of this could be seen from the power tussle involving late party leaders such as S Samy Vellu, S Subramaniam, MG Pandithan and V Govindaraj in the past years.

If this wasn’t enough of a headache, disunity within the party’s branch and divisional level also further undermined and eventually led to a split in the party.

This was when then MIC vice-president Pandithan quit the BN component party and, together with his supporters, went on to form the Indian Progressive Front.

Protect Indian community’s interest

These internal strifes and external headwinds continued to chip away at its base and support, as well as contributed to a fragmentation of the Indian vote.

Though the Indian vote began deserting, the MIC remained strong due to the electoral seats with the help of Malay, Chinese and other voters.

There is no Indian majority seat at either the state or parliamentary constituency level nationwide, where the ethnically based party can claim to be its fortress.

In GE14, seven parliamentary constituencies had 20,000 and more Indian voters, with the Kota Raja seat the highest in both percentages and the number of votes, namely 27.68 percent with 41,249 Malaysian Indian voters.

The second-most number of Indian voters can be found in Petaling Jaya, with 27,535 voters (19.54 percent), followed by Klang with 25,523 voters (17.9 percent).

If it's bad enough that its electoral fortunes seemed to have slowly disappeared after the 2008 general election, recent developments within the party are also not providing any comfort.

The move by former MIC vice-president C Sivarraajh and Selangor MIC Youth chief P Punithan to quit the party shows that not all is well.

In addition, the suspension of KR Parthiban for taking the stage at a Perikatan Nasional event as well as the sacking of the former Ijok state assemblyperson did no favours to the beleaguered party.

Since its inception in the 1940s, MIC’s main role has been to protect the Indian community’s interest as well as address its socio-economic development.

The party’s late president Samy Vellu said the party, in its initial years and subsequently, acted and played a role as a non-governmental organisation in aiding and helping the Indian community.

Maybe this approach can be re-looked at but infused with new approaches and other proactive measures to address the Indian community’s needs in Malaysia. By going back to its past roots in a broader sense, the party may yet revive its future political and electoral fortunes.

Yet solely depending on the Indian community, with many now shunning the party, especially the younger, educated and economically well-off generation, turning it around may be easier said than done.

Gone are the days when MIC leaders could woo supporters through a song-and-dance approach.

The party and its leaders will need serious new approaches and ideas.

Now that it no longer holds electoral power, the MIC, long seen as the saviour of the Indian community, is no longer seen as their defender. - Mkini

B SURESH RAM is a member of Malaysiakini Team.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.