A cursory inspection of the courses offered by and the faculties of local universities will show a dearth in the study of philosophy. There is no dedicated standalone faculty, programme or department currently in existence.

Yet, this is entirely in keeping with the rigid focus of an educational system geared towards quick national development, the sort that Stem courses are meant to facilitate. The result is the evolution of a system prizing the pursuit of hard facts, solid answers and regurgitation.

Amid this backdrop, grassroots efforts are underway to transform the relative lack of attention to this discipline and to encourage the pursuit of philosophy when it can be seen as a bourgeoisie, elitist pursuit – serious scholars can only pursue the subject abroad.

There are many assumptions about the nature of philosophy and many misconceptions that go along with it. The dictionary definition – literally, the love of wisdom – as taken from its Greek roots, can be our starting point.

What we traditionally view as philosophy in its Western sense draws on a storied intellectual genealogy – the legacy of thinkers like Plato, the Stoics, Thomas Hobbes, Rene Descartes and Jeremy Bentham.

On the surface, it seems to be a Eurocentric preserve, given its traditionally heavy association with European schools of thought.

Yet, there are various conceptions of philosophy, and being in Malaysia we have plenty of exposure to non-European perspectives – we are able to draw on Islamic, Buddhist, Chinese and Hindu philosophy, for instance.

With these come different ways of seeing the world and evaluations of ethics and reason. Unfortunately, the overarching trend towards specialisation has left philosophy outside the “applied” (or bluntly, financially profitable) fields of social sciences, economics and science.

Making philosophy relevant

But if the question of the importance and “practicality” of philosophy comes up, we can still look at two particular ways that philosophy has shaped the modern world.

The philosophy and radical theories of Karl Marx, grounded in his studies of politics and capital, or Peter Singer, who worked on altruism and animal welfare, continue to have implications for greater humanity and an understanding of our human condition.

Certainly, Marx and Singer were not just engaged in intellectual talk and armchair exercises. And if anything else, the skills of philosophy graduates can be surprisingly market-friendly.

Chew Zhun Yee hopes to dispel the misconceptions and encourage the inculcation of philosophy at an everyday level.

She became a co-founder of the Malaysian Philosophy Society – an NGO dedicated to pioneering and leading “the culture of practical philosophy” in Malaysia – in a roundabout fashion, having first developed an interest in the subject during a gap year before starting university.

Recognising the need to break away from the traditional linear model of learning, Chew partnered with Dr Tee Chen Giap to set up MyPhilSoc, which they view “as a platform to shift Malaysians’ attitudes towards philosophy, encouraging them to see philosophy as an important skill in their everyday life”.

Their focus is on practical philosophy, as operationalised through events such as TerraThoughts and Philoliving as well as Instagram outreach – all of which serve to ask “specific philosophical questions, (and) apply specific philosophical interpretations on real-world issues”.

Relevant everyday struggles become exercises and demonstrations of philosophy.

A debate on the ethics of getting vaccinated puts the principles of Bentham’s Utilitarianism into action while stepping back as a way of dealing with ungrateful bosses means practising the Dichotomy of Control, as espoused by the Stoics.

In short: they work towards “making philosophy relevant, useful and inseparable from contemporary society”. And there is a steady stream of support for their work from students, graduates, academicians, policymakers and activists – ranging from teenagers to septuagenarians.

Philosophy is rooted at the heart of our fields of knowledge, our ethics and strategies for managing everyday life, even. The trick is to embody this realisation in everyday life.

“If you imagine all concepts as nodes forming a web of knowledge, philosophy would be the central node where all other concepts branch out from,” Chew and Tee said.

They are careful to minimise the use of jargon and technical terms in order to better reach out to the general public, and this is not an effort that can be undertaken alone. Rather, developing an ecosystem is crucial.

“The rationale is that, by building an ecosystem and working together with other relevant bodies, we stand a better chance to establish philosophy’s existence here in Malaysia.” Chew and Tee explained.

In an environment ravaged by Covid-19, political uncertainty and the strain on mental health, a place and space for scepticism, focus on intellectual discourse and capacity for critical thinking are more important than ever.

The same realisation is shared by other groups, operating in English and Malay at least, which include the local adherents of Socrates Café, university-level philosophy clubs, as well as Persatuan Pendidikan Falsafah dan Pemikiran Malaysia (PPFPM), founded by retired UKM mathematician Mohammad Alinor Abdul Kadir.

It’s not just every day where they are putting their focus. They are partnering with PPFPM on the development of a formal philosophy education programme for high schoolers and pre-university students through the Kritikos Fellowship, which is soon to be an NGO in its own right.

By being involved in the planning, execution, and eventual data-gathering of this six-week pilot programme, the hope is to demonstrate the importance of more established philosophy education to the Malaysian education system.

At the very least, it will be a way of slowly catching up with more established philosophical faculties across the region, such as in Taiwan and Singapore.

Malaysian philosophy free of colonial orientations

In our Malaysian context, especially with the debate on decolonisation and the indigenisation of knowledge still going strong decades after independence, a discussion on the Eurocentric nature of much of our academic knowledge is inevitable.

In the field of history, famously, post-colonialism and subaltern studies have challenged the existing schools of thought, as pioneered by figures such as Edward Said and Ranajit Guha.

The underlying concern is the necessity to avoid blind obedience to existing standards, allowing for the possibility of fresh interpretation and development of knowledge.

Moving away from history specifically and edging closer to home, Syed Hussein Alatas’s conception of a School of Autonomous Knowledge comes to mind: one which “urged scholars to develop an autonomous social science tradition, a tradition of knowledge production that was free of Eurocentric, colonial and other biased orientations”.

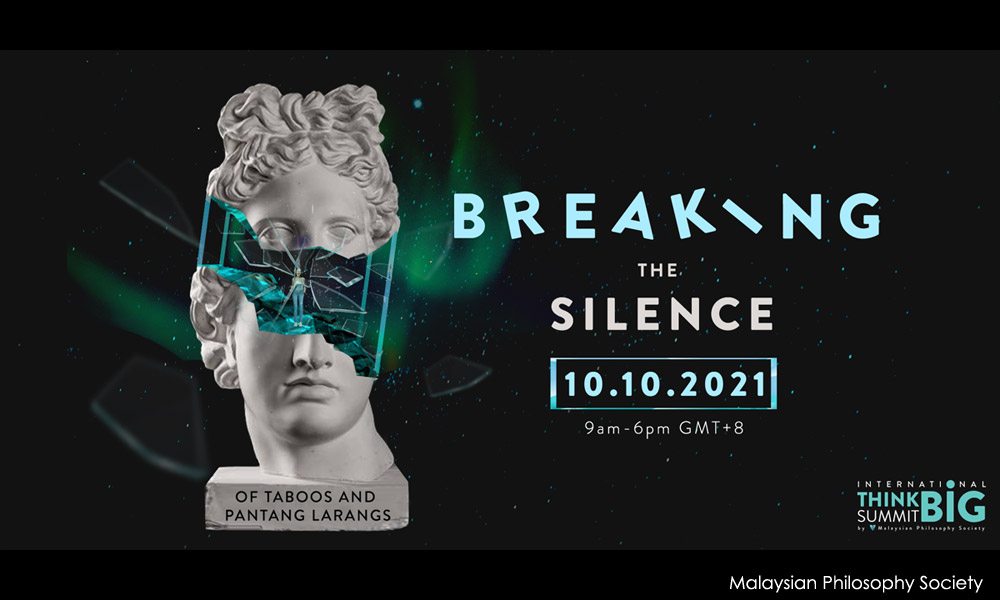

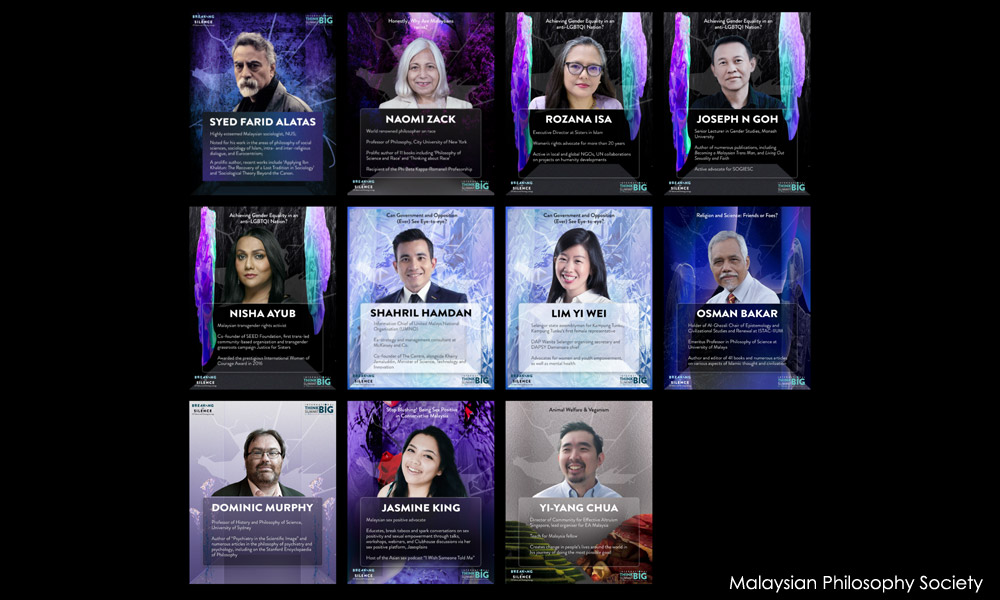

Incidentally, his son, Farid Alatas of the National University of Singapore, following in this tradition, is a keynote speaker at MyPhilSoc’s International Think Big Summit in October, speaking on “the epistemology of taboos – how we come to acquire ‘knowledge’ or meaning of taboos”.

The Summit’s focus on “Breaking the Silence”, involves various topics – politics, racism and sexuality, for instance – which have been “silenced” in their metaphorical and literal senses.

For the most part largely unquestioned for decades, enabled by stable economic growth and relative political stability, Chew and Tee note that “during this pandemic, we have observed a rise in systemic discrimination against other races and ethnicities, gender inequalities, erosion of democratic ideals and power abuses, among many others”.

For that reason, the need to speak up about such taboos is timely and brings together a variety of speakers, ranging from professors Naomi Zack of City University of New York to Dominic Murphy of the University of Sydney.

One of the topics to be explored revolves around the supposed division in the discourse of religion and science (which were traditionally mutually reinforcing disciplines), now separated by their own cadres of practitioners, bureaucracies and repositories of specialised knowledge.

Their hope is that a frank discussion will “prove that religion and science can coexist or even flourish with each other.”

The need to ask questions and have discussions is crucial to the development of a critical, philosophical tradition. A tight focus on the control of the narrative and the neat supply of fixed facts has characterised Malaysian education for decades, perhaps becoming part of the reason for our continued lack of a more ingrained philosophical tradition.

The capacity to produce technicians, medical staff and data scientists exist, yet the infrastructure needed for philosophy – one of the oldest fields of knowledge – remains curiously lacking.

But none of this has to be permanent, for as Chew and Tee explained: “Philosophy challenges us to suspend our judgment and cognitive biases, and use rational argumentation to achieve greater truth and clarity in our thoughts.” - Mkini

WILLIAM THAM WAI LIANG is an editor at large for Wasifiri. His new novel, The Last Days, is set in 1981 and covers the continuing legacy of the Emergency. His first book, Kings of Petaling Street, was shortlisted for the Penang Monthly Book Prize in 2017.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.