The discovery of a small photographic collection sets Alan Teh Leam Seng on the path to discovering intriguing details of prominent mosques in the country

A medium-sized envelope, scribbled with the words "Malayan Mosques", is slotted between the pages of an old magazine recently salvaged from a recycling centre, together with a smattering of books and documents.

With piqued curiosity, my quivering hands retrieve its contents, which turn out to be more than two dozen black-and-white photographs and colour post cards. Accompanied by meticulously written notes, they weave a compelling tale of early Islamic landmarks in our country.

OLDEST MALAY TIMBER MOSQUE

A feeling of utter elation overwhelms me after noticing several images related to Masjid Kampung Laut. Clearly standing head and shoulders above the others in terms of historical importance, this renowned Kelantan place of worship holds the enviable record for being the oldest Malay timber mosque in Malaysia.

Unlike majestic principal masjid in state capitals, which were built with bricks and mortar, village mosques like Masjid Kampung Laut were usually constructed using chengal wood, widely considered the most durable and, thus, prized of all timber.

Originally located in a quaint village that shares the same name, Masjid Kampung Laut has survived the test of time by avoiding fire and civil unrest, which were prevalent in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Its rural orientation also played a key role in shielding it from evolving Malay architectural fashions that began in earnest during the early 20th century.

Although the exact date of Masjid Kampung Laut's construction has been lost in the sands of time, locals maintain that the mosque has already existed for at least five generations.

Oral tradition, passed down by village elders, claims that it was constructed by a group of Muslim voyagers, who sought respite in the village while replenishing their supplies.

Many believe that these pioneers went on to build similar places of worship in Melaka and Damak in Java, Indonesia.

Despite the chronological ambiguity, scholars are confident that the mosque must have existed in Kampung Laut for at least three centuries. They arrive at this conclusion based on the established fact that the "Raja Kampung Laut" title was first conferred on one of the 11 sons of Long Yunus, founder of the present Kelantan dynasty, who ruled from 1763 to 1798.

The honour must have been bestowed in recognition of the village's sizable population and strategic location along lucrative land and maritime trade routes.

FLOOD DAMAGE

As the name suggests, the mosque and village were once within close proximity to the sea, which was a major source of prosperity. The same, however, could not be said for the adjacent waterway.

Over the centuries, the mighty Sungai Kelantan gradually changed course and chipped away land almost a kilometre wide, on which many of the oldest houses and graves once stood.

By the 1950s, erosion had reached such an extent that Masjid Kampung Laut, which was purposely built in the village centre to signify its importance in the religious and social lives of the people, found itself perching precariously on the very edge of a high and unstable bank. The situation came to a head when the Great Kelantan Flood struck in December 1966.

Inundation swept swiftly down from the nearby hills and water rose steadily until the roof level.

After the flood had subsided, villagers were horrified to discover that the entire verandah facing the river had collapsed and disappeared downstream, while several undermined pillars were suspended mid-air.

Damage was more extensive than expected as the concrete ablution tank had been washed away into the river, and the wooden flooring, together with a section of the roof, were tilting dangerously.

Almost immediately, the authorities declared the building unsafe and the mosque that once served as an important meeting place for the people, as well as the sultan and religious leaders, was closed down.

A year later, a decision was made to build a new stone and concrete mosque some distance inland, and the abandoned Masjid Kampung Laut was left to fade into the background, waiting in silence for another deluge to put an end to its existence.

KNIGHT IN SHINING ARMOUR

Fortunately, that did not come to pass thanks to intervention by the Malaysian Historical Society (Persatuan Sejarah Malaysia).

Conscious that time was of the essence as another flood, even a minor one, would bring down the unstable structure and render reconstruction impossible, the mosque's "knight in shining armour" speedily secured permission from the state authorities in 1968 to dismantle the dilapidated structure and relocate it 20km away in Kuala Krai's Kampung Nilam Puri, where it will be safe from the ravages of the ravenous Sungai Kelantan for all eternity.

Dismantling work began in earnest on Nov 3, 1968, with the meticulous numbering of every single beam and plank making up the structure.

Coinciding with Shaʻaban 12, 1388, a date considered auspicious by master builder Hussein Salleh of Kampung Bunut Payong, the historic building was taken apart in excellent weather throughout the remainder of that month.

Aided by able supervisor Haji Zain Haji Awang Kechil from Kota Baru, Hussein took time to marvel at the skills of the ancient builders as not a single nail was used in the building, and also expressed supreme relief that most of the chengal timber was still good.

Reconstructed directly opposite the Kelantan Foundation for Higher Islamic Studies (known today as the Academy of Islamic Studies, Universiti Malaya), the building, complete with a new verandah and other skillfully made replacements, remained true to its original shape and size, albeit some unavoidable minor alterations.

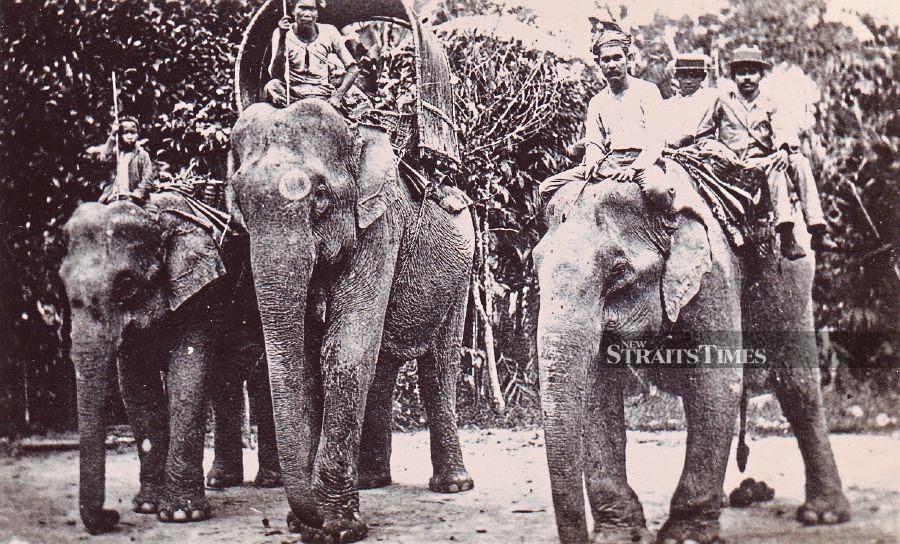

Originally, Masjid Kampung Laut was eight feet (2.43m) high from the ground, and the generous height allowance gave opportunity for the Raja and other high-ranking officials to tether their elephants under the building while they prayed.

Over the course of countless floods, the ground gradually rose in tandem with silt deposition. The towering supporting pillars had vanished from sight by time the devastating 1966 flood struck.

During excavation, it was found that the hardy chengal had started to decay after being buried in mud and exposed to water for hundreds of years. As a result, the lower half of each pillar had to be discarded, and that unavoidable decision caused the reconstructed building to have just four feet of leeway from the ground up.

DUTCH ERA MOSQUE

While overwhelmed by relief that Masjid Kampung Laut, which nearly ceased to exist, had been given a new lease of life thanks to conservation efforts, focus then shifts to the other images in the collection.

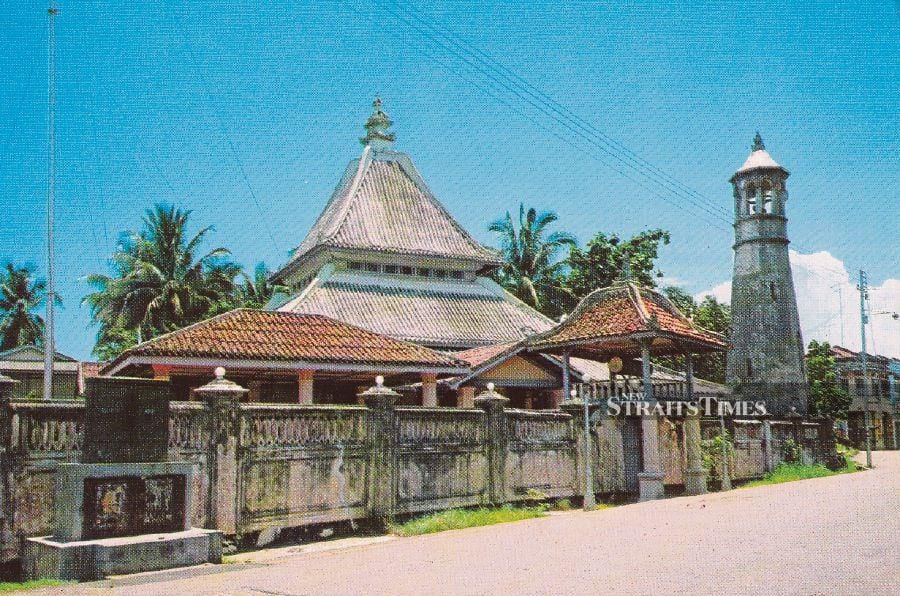

A colour picture postcard featuring Masjid Kampung Hulu catches the eye thanks to its pyramid roof, which bears close resemblance to the one on Masjid Kampung Laut.

Considered the third oldest Islamic religious site in the country and among the most beautiful mosques in Melaka, this key landmark was built in the 18th century with financial contribution from the Dutch East India Company, which held sway over the important regional entrepot during that period.

Advocating religious tolerance in Melaka, the Dutch entrusted Datuk Samsuddin Arom, a wealthy and pious community leader, with the task of building Masjid Kampung Hulu.

Hailing from humble beginnings, Samsuddin's presence in Melaka could be traced all the way to the time when a heated family dispute prompted his father, Arom, to leave China and seek a better future in the Malay Archipelago.

Fate had it that his ship capsized off the coast of Melaka, and he was said to have been rescued by a local muezzin.

Finding safe shelter living with his saviour's family, Arom eventually married the muezzin's daughter after embracing Islam and went on to be a successful businessman, who donated generously to the poor and made many land endowments to aid religious causes.

Following in his father's footsteps, Samsuddin continued to use his wealth for the betterment of others. His benevolence culminated in the endowment of a piece of land to build Masjid Kampung Hulu.

The last few photographs, featuring more recent mosques built in the last century, show a distinct shift from the use of timber to versatile concrete.

Majestically designed to mirror breath-taking Neo-Mughal influences and Indo-Saracenic styles, many of these stunning colonial era landmarks still hold on to their pride as principal mosques in their states.

DELAYED BY ELEPHANT FIGHT

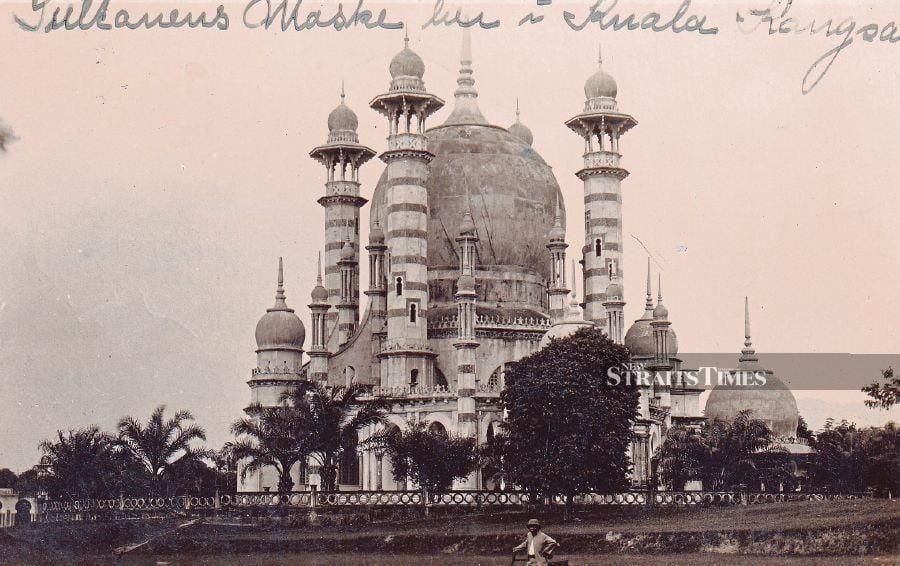

Among these is the magnificent Masjid Ubudiah in the Perak royal town of Kuala Kangsar. Identified by its imposing central dome flanked by four identical minarets, the mosque was designed by Arthur Benison Hubback, an architect responsible for designing many majestic Malayan buildings, including the Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh railway stations.

Commissioning its construction after convalescing from a severe bout of illness, Perak ruler Sultan Idris Murshidul Adzam Shah I laid the foundation stone and officiated at its groundbreaking in Bukit Chandan on Sept 26, 1913.

Unfortunately, the 28th sultan of Perak's health took a turn for the worse, and the monarch died in 1916, just one year shy of the mosque's completion.

Sultan Idris could have seen the completion of Masjid Ubudiah if not for a series of delays brought about by an incident involving two male elephants — Kulub Chandan and Kulub Gangga — belonging to the sultan and his nobleman, Raja Chulan, respectively.

The clash, said to have taken place during a royal circumcision feast, lasted for hours within the palace grounds and caused extensive damage. The melee eventually brought the battling pachyderms to the area where materials for the mosque construction were kept.

The bulls laid waste to everything in their wake, including priceless Italian marble slabs, before the mahouts took advantage of their waning stamina to set them apart.

By the time fresh orders were placed, World War 1 had broken out in Europe. Apart from escalating costs, widespread hostilities resulted in the replacements arriving behind time as they had to be transported via Africa's Cape of Good Hope instead of the shorter and cheaper Suez Canal route.

While placing the precious images in protective folders, it becomes evident that our nation is indeed fortunate to have such a diverse collection of mosques, each with its own amazing tale to tell.

At the same time, more should be done to in terms of conservation to ensure that these landmarks continue to stand the test of time and be cherished for many, many more generations to come. - NST

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.