My earlier research found that socio-economic class differences were pivotal in 2018, as an erosion of support among those of lower incomes for Umno decisively contributed to the change of government and defeat of Najib Razak.

Then, higher cost of living, poor implementation of the GST (which increased inflation) and limited expansion of the social safety net undercut support levels. In GE14, the base of lower-income voters that Umno relied on collapsed.

The findings for GE15 show that class differences/backgrounds were the second most important social determinant of voting after ethnicity and ahead of generation, gender, and urbanisation differences.

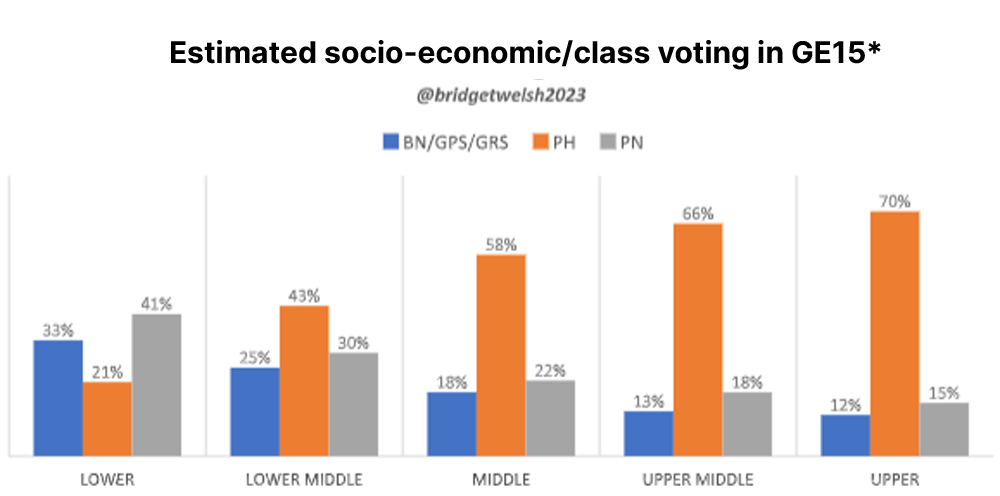

Income levels were tied to voting in GE15, with Pakatan Harapan decisively winning wealthier voters and only a small share of the lowest-income voters.

It is thus no wonder that the Anwar Ibrahim government’s approach has been to try to woo voters, especially from lower class backgrounds, as this group of voters are both numerous in terms of voters and key swing voters.

While Umno/BN (+GPS/GRS) get the largest share of support from lower-income voters, it was Perikatan Nasional (PN) that won the majority of lower-income voters nationally. These voters, the most economically vulnerable, swung their support.

This can be credited to the perception that then prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin during the Covid pandemic increased social safety net support for those in need at a pivotal time.

Not to be left out are the populist measures of PAS, which have led to greater distributive measures by the state governments where the Islamist party is at the helm.

As such, PN cut deeply into Umno’s traditional lower-income political base in GE15, which opted not to return to Umno after 2018.

Understanding class and voting

To date, GE15 analysis – and that of Malaysian politics generally – places limited attention on the role that class plays in national politics. A myopic focus on race and the use of racialised politics obscures attention to arguably one of the most serious divides in Malaysian society, that of income divisions and class inequality.

As with urbanisation (the previous article in the series), this socio-economic division is interpreted incorrectly through a racial lens, with the misperception that it is the Malays who are poor and other communities not so.

While the numbers of economically vulnerable Malays and other Bumiputera are larger, all ethnic communities in Malaysia have those living in poverty and at risk of rising costs of living and inadequate wages. The division between the rich and the poor is stark in Malaysia and cuts across all communities.

Scholarship on voting in Malaysia has not adequately included class. Unfortunately, the various pollsters ignore this variable with their own myopic race-focused lens. In part, this is also a product of the methodological challenges in looking at how income impacts voting.

The issue of class has largely been studied indirectly. Studies of the role of patronage and funds/spending in campaigns, especially vote buying/gifts/subsidies for transportation implicitly are addressing this factor.

There is also considerable attention to the need for social safety nets beyond discussions of voting, yet the issue of political reciprocity and co-dependence is comparatively unexplored, with the links between social distribution and political support with even less adequate attention. (BR1M in GE13 was an exception.)

Related issues of education background/levels, social mobility prospects, and more are also not adequately studied.

My analysis shows there is a need to better include class and income considerations in the political analysis of voting. Over the last two general elections, the statistical findings on class have proved important.

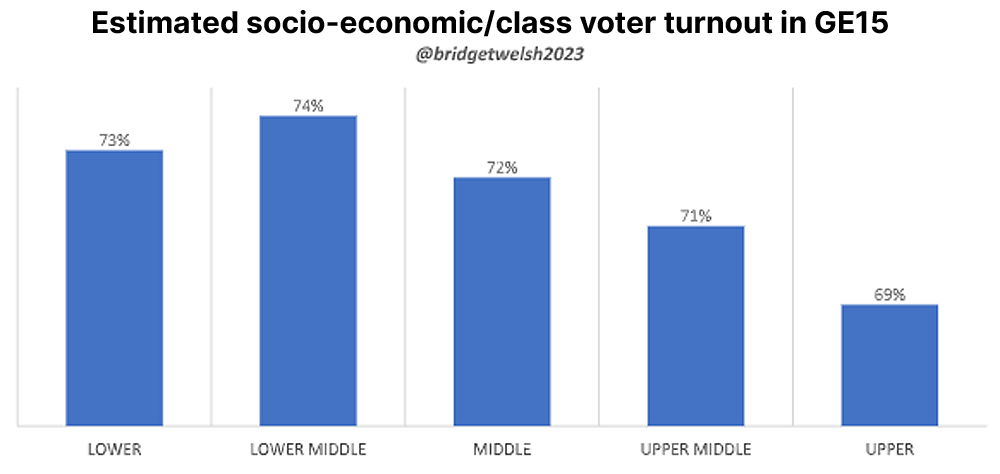

In my study of how class/income impacted voting, I built a data set of over 2/3rds of polling stations across Malaysia, estimating average income in localities.

These were divided into different brackets, from below RM3,000 household income at the lowest level to above RM20,000 estimated household income at the highest level. The data was gathered through fieldwork and local expert interviews.

Again, ecological inference was used to estimate voting behaviour. One should see these findings as estimates upon estimates, as capturing income levels across groups (even small groups) is challenging.

The statistical robustness of the value findings, however, suggests considerable value in this framing/method.

Class voting findings in GE15

They reveal that Harapan won over the support of wealthier voters, from those earning lower middle incomes (RM3,000-6,000 household monthly) and above.

It was only able to win the estimated support of 21 percent of those earning household incomes before RM3,000. The higher the income bracket, the higher the support for Harapan.

Both Umno/BN (+GPS/GRS) and PN won more support from poorer voters. PN did especially well among this group in GE15, an estimated 41 percent. Part of this stems from the ‘Abah’ factor and the PAS state government’s populist spending, noted above.

Yet, what cannot be ignored is PN’s actual spending during the GE15 campaign itself. As incomes rise, PN’s support declines, although consistently this coalition wins more support than Umno/BN across all income/class brackets. PN won an electoral foothold across incomes.

The same cannot be said for Umno, which has experienced an erosion of support. Umno/BN’s support among the most economically vulnerable voters was only an estimated 33 percent, the coalition’s highest share.

Umno/BN (+GPS/GRS) long lost the majority of wealthier voters, but since Najib’s tenure, it also has seriously eroded its lower-income voter base.

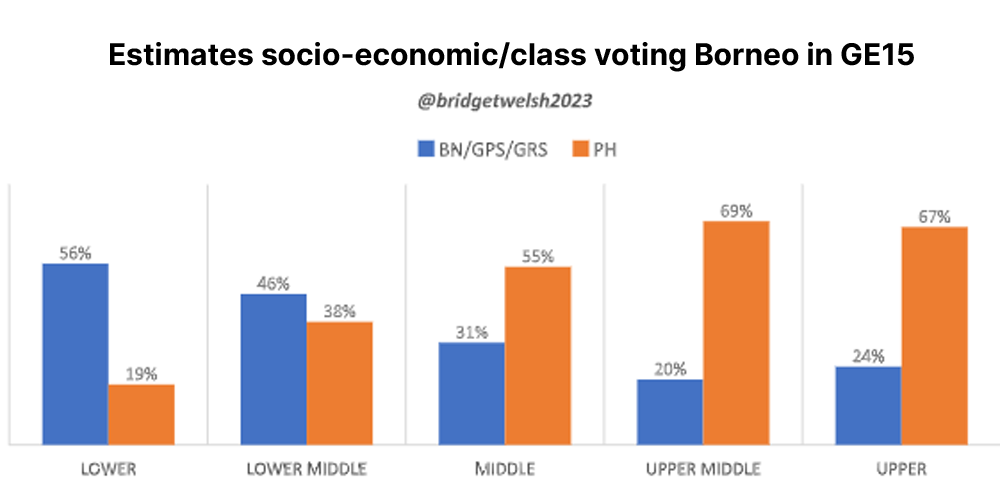

A closer look at the data finds that considerable support for Umno/BN among the most vulnerable voters (analysed together with GPS and GRS) was higher in Borneo.

The traditional BN held onto its lower-income base, even as the new coalitions of GPS and GRS contested. There was a similar class dynamic for Harapan support in Borneo, with greater support among wealthier voters.

Class-aware policies and politics

Given the salience of socio-economic conditions/class in voting behaviour and the pivotal role of lower-income voters as swing factors in electoral outcomes, contributing to changes in governments, the deficit of substantive policy measures to reform the social safety net is a serious issue.

Anwar’s government has prioritised social distribution. Yet the measures so far have largely continued previous initiatives (although some have been given new names). There are promised new measures in the pipeline. How long and whether these will be effective remains to be seen.

The overall approach, however, appears to be one of distribution, addressing the effects of vulnerability, rather than on creating conditions to address causes of underlying poverty and obstacles to social mobility.

This focus has been an integral part of its Madani branding, aiming to build moral and social legitimacy as a compassionate government.

At the same time, the Anwar government risks losing its socio-economic political base, and wealthier voters, some of whom are resistant to reforms that restructure wealth, change distribution (patronage) patterns, and increase their tax burden, especially at a time when the economy has not yet recovered from the negative impact of the Covid pandemic.

Few appreciate that disappointment among many businesspersons in Harapan 1.0 undercut support for the 2018-2020 Mahathir government.

Resistance to reforms extends well beyond race. Those who profess equality for different ethnic communities do not necessarily extend this to those of different incomes.

Highlighting socio-economic/class in voting patterns showcases another balance that Anwar’s government has to make. Here too (like with ethnic support), his government is appealing for support to those who did not vote for him.

The question will be whether the measures in place are enough to win the support along class lines that Harapan has never really had.

At a time with still rising inflation and the persistent vulnerability of too many Malaysians, the need to meaningfully address issues of those most at risk is urgent. This goes well beyond elections, as it speaks to Malaysia’s future: Malaysia as a society is vulnerable as long as large numbers of Malaysians remain vulnerable. - Mkini

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia’s Asia Research Institute (Unari). She is also a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.