Last week, the Department of Orang Asli Development (Jakoa) director-general Sapiah Mohd Nor was awarded a datukship.

I’m sure the award was well deserved and Sapiah joins her brother, Dewan Rakyat deputy speaker Ramli Mohd Nor, and relative Senator Ajis Sitin, among Orang Asli people who received such honours.

When receiving the award, Jakoa’s first female director-general said her department was actively conducting studies and engagement sessions to empower the Orang Asli Act 1954 (Act 134).

"I hope, in five to 10 years, the Orang Asli community will own land with titles on par with mainstream society (through) the empowerment of Act 134,” she said, adding that the Act would help Orang Asli on issues such as land ownership and registration of marriages and births.

Earlier this year, Ramli called for the amendment of Schedule Nine of the Federal Constitution so as to include the welfare of Orang Asli into the concurrent list with shared federal-state powers.

This was because Orang Asli issues are usually dealt with by Jakoa, but the land that they occupy comes under the jurisdiction of individual states.

While all this is pertinent, I am not happy with what I see as evasion on the issue of Orang Asli minority languages facing extinction.

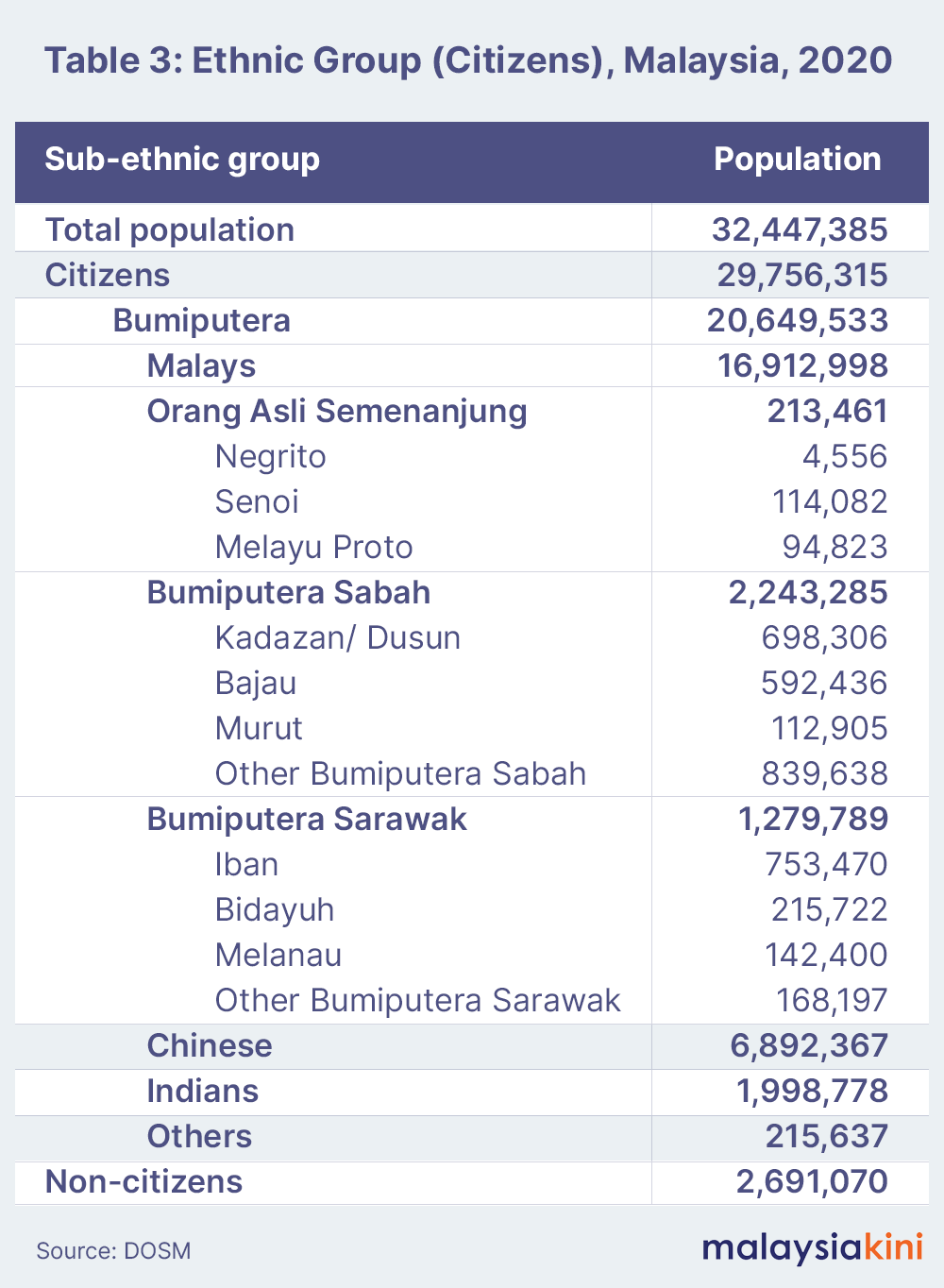

The Orang Asli in the peninsula are divided into three main groups - the Negrito, Proto-Malay, and Senoi. Each of these is further divided into six groups.

The disparity of size among the groups is wide. Based on the 2010 census, the largest groups such as the Semai, Temuan, Temiar, and Jakun made up the bulk of the 215,000 registered Orang Asli.

On the other hand, the Bateq, Jahai, Semoq Beri, Jah Hut, Mah Meri, Orang Seletar and Orang Kuala numbered less than 6,000, while the smallest of the tribes - the Kensiu, Kintak, Lanoh, Mendriq, Che Wong and Orang Kanaq, all have less than 1,000 registered people per tribe!

This actually means that they are in danger of extinction as the smaller groups are nomadic and gravitate towards larger groups, slowly losing their language, particularly when they intermarry with members of these other groups.

The situation is no different in East Malaysia with smaller native groups. In 2008, I visited the home of former Sarawak deputy chief minister James Wong and he showed me a photo of his childhood friend.

“His tribe is extinct now,” he said casually. I was horrified.

Latest census alarming

Indeed, I have been increasingly alarmed about the possibility of the smaller groups disappearing particularly as the 2020 census just lumps them together.

The six Negrito groupings total just 4,556 out of the 213,461 peninsula-based Orang Asli registered in the census! But there is no individual breakdown of the numbers of each group.

It is similar, by the way for Sabah and Sarawak, where many smaller groups are just lumped together.

My colleagues and I have been trying to get Sapiah to consent to an interview during the two years since her appointment as director-general but to no avail.

I have forwarded questions on this subject matter to Sapiah, Ramli, and the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) without getting a response.

Why was the 2010 census more detailed and what is to prevent unique cultures and languages from slipping away, to be lost forever?

In 2019, Jakoa, under then-director-general Juli Edo, told me that they were compiling dictionaries but this year, I can’t even get any follow-ups on the matter from Jakoa.

In June, Bernama ran a story saying that experts who conduct research on Orang Asli languages in this country expect the Mendriq language to become extinct within the next 20 years if no preservation measures are taken.

Mendriq are only found in Kelantan. Currently, they live in three locations namely Kampung Lah in Gua Musang, and Kampung Pasir Linggi and Sungai Tako in Kuala Krai.

Kampung Lah village chief Ali Lateh said that many Mendriq intermarried, especially with Malays, and this has occurred significantly since the early 1990s.

"Because the couple does not know the Mendriq language, Malay is used. From here, the Mendriq language is slowly being marginalised.

"Indeed, I am quite sad when our young people use the Mendriq language less and less, and I think this language will become extinct and disappear from the world if there is no effort from our own community and the government,” he told Bernama.

Ali said that it is now increasingly difficult to find Mendriq people with their “original” characteristics - who are curly-haired, dark-skinned with a wide round face, flat nose, and short chin.

"As for now, there are less than 10 people (with the physique and appearance of the original Mendriq tribe) due to many intermarriages and the children also have hybrid faces," he said, adding that there are about 380 residents in Kampung Lah and it is the largest community of the Mendriq tribe.

UKM’s Fazal Mohamed Sultan, lecturer at the Center for Language and Linguistics, said that based on his research since 2007, it is highly likely that the language will become extinct within the next 20 years.

What's more, at the moment, there is no action from the authorities to protect the Mendriq language, or other Orang Asli languages, as the Education Ministry has only introduced the Semai language as a subject in schools that have many students from that ethnicity.

‘Education a struggle’

“I just see that there is a need for this programme to be extended to all Orang Asli tribes, especially the Negritos, because as far as I know, so far, most of the Orang Asli teachers are from the Malay Proto and Senoi groups. There are no Negritos at all," Fazal said.

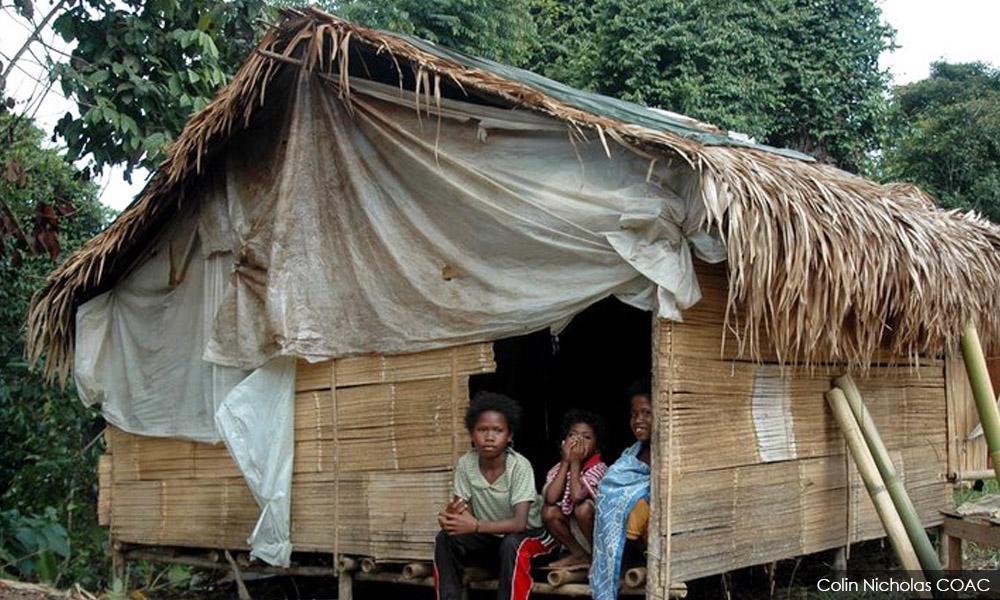

Similarly, the election campaign in Pulai showed that the Seletar tribe was struggling to keep their children focused on education and committed to preserving their language and culture.

Tok Batin of Kampung Orang Asli Bakar Batu, Kais Kie told Bernama that the state government has provided various assistance to the community, including sending 10 children to SK Taman Sutera, but more needs to be done.

"The children in the village would rather follow their parents to the sea than go to school.

“It would be better if there is a teacher in the village to hold classes, including computer classes, to at least teach them the basics of using computer equipment and also other skills," he added.

Kais said that in the village, 15 children aged between seven and nine years have dropped out of school.

So that’s the situation on the ground today.

And I hope the honourable leaders of the Orang Asli community at large will take direct action, instead of evasive action. - Mkini

Martin Vengadesan is associate editor at Malaysiakini.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.