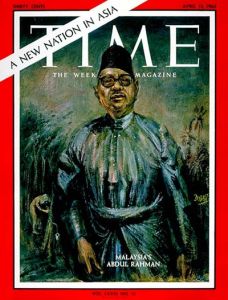

Malaysia is a miracle nation. When the Union Jack came down in 1957 and Malaya became a member of the British Commonwealth, many thought we would soon fail.

Malaysia is a miracle nation. When the Union Jack came down in 1957 and Malaya became a member of the British Commonwealth, many thought we would soon fail.

We had one of the oddest constitutions in the commonwealth. We defined “Malays” and granted them a special position. We entrenched nine Rulers and at the same time stripped them of powers. We “barred judicial review of some breaches by Parliament of the fundamental rights of citizens” (Shad S Faruqi).

We were beset by internal and external strife. There was massive poverty. Economic activity was race-based. A communist insurgency was on. Many institutions – including the Police Force – continued to be helmed by the British, who also owned vast plantations and most large corporations. Indonesia sought to subjugate us.

Yet despite predictions of failure, unlike many other nations in the commonwealth, we did not tear up our constitution. We merely made over 650 amendments to it.

Some amendments were good. For instance, a special court was established to prosecute the Rulers. Some amendments were awful. For instance, numerical limits on the sizes of electoral constituencies were removed. As a result of this our Election Commission can pretend that one is approximately equal to four. (In the 13th general election, Sabak Bernam had about 37,000 voters while Kapar had about 144,000 voters.)

Our Constitution has kept us from crashing as a nation over the past 58 years. Due to the role given to the Rulers, governing Malaysia requires more internal diplomacy than governing any other nation. The modus operandi of PERKASA, Malaysia’s crude Malay superiority group, is to interpret everything they oppose as a threat to the Rulers. That is also the politics of the two Malay political parties, UMNO and PAS. They compete to present themselves as defenders of the honour of the Rulers.

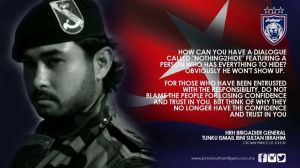

Our Constitution has kept us from crashing as a nation over the past 58 years. Due to the role given to the Rulers, governing Malaysia requires more internal diplomacy than governing any other nation. The modus operandi of PERKASA, Malaysia’s crude Malay superiority group, is to interpret everything they oppose as a threat to the Rulers. That is also the politics of the two Malay political parties, UMNO and PAS. They compete to present themselves as defenders of the honour of the Rulers. Malaysian Indians have caught on: a deliberate decision to adopt the modus operandi of the Malay parties is the only tenable explanation for the Police report which 46 “Indian NGOs” made last week against Minister Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz for his “we will whack you” rejoinder to the Crown Prince of Johor when the latter criticised Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak. The NGOs wished to be seen as supporters of the Prince who may one day rule Johor.

Malaysian Indians have caught on: a deliberate decision to adopt the modus operandi of the Malay parties is the only tenable explanation for the Police report which 46 “Indian NGOs” made last week against Minister Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz for his “we will whack you” rejoinder to the Crown Prince of Johor when the latter criticised Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak. The NGOs wished to be seen as supporters of the Prince who may one day rule Johor.

I’ve been thinking about our constitution because Malaysia’s Islamist party, PAS, is trying to get Parliament to give the state government of Kelantan the right to legislate on matters which are currently the sole prerogative of the federal government.

Our government has responded to PAS by offering to support Kelantan’s desire if PAS agrees to get into bed with UMNO, Malaysia’s hegemonic Malay-Muslim party.

Four citizens have responded to our government by filing an injunction in court to prevent the tabling of Kelantan’s desire in Parliament. The four citizens have caused the parliamentary tabling of Kelantan’s desire to be put on hold until the court hears and rules on their argument that a fundamental change cannot be proposed without first obtaining the consent of the people.

The citizens’ injunction reminded me of another injunction, filed 52 years ago. In 1963 the state government of Kelantan filed an injunction to stop the federal government from forming the Federation of Malaysia by bringing in Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak as new members.

The basis of Kelantan’s argument was that fundamental changes were being proposed without first obtaining the consent of Kelantan. (The term “basic structure” was not used at that time.) The changes did seem fundamental. The three “new members” would not be equal partners with the prior members. Sabah and Sarawak would have disproportionately large representation in Parliament, would have the right to impose domestic immigration controls and would have the right to impose taxes beyond what the prior members had.

Islam would not have ceremonial pre-eminence in Sabah and Sarawak. (In the interest of brevity I omit Singapore’s privileges.) PAS/Kelantan raised the issue before the court as a challenge of state power by the Federal government. One of their five arguments was, “Constitutional convention dictates that consultation with Rulers of individual states was required before substantial changes can be made to the Constitution” (Johan S Sabaruddin).

The court had to act rapidly, as Kelantan began the action on September 10, 1963, a mere six days before Malaysia day. The court ruled against Kelantan. Malaysia was not aborted. The decision was clear. The Rulers need not be consulted. The people were sovereign, through Parliament. The constitution triumphed. The miracle continued.

The 1963 constitution should be the lens through which we look at the challenges of governing Malaysia, exploitation of patronage and attempts to thwart federalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.