The Obama-styled "unity" posters of Mohd Shafie Apdal are facing off against the #kitajagakita slogan appropriated Perikatan Nasional posters of "abah" Muhyiddin Yassin. On the surface, this is a battle of communication strategies and messaging. At its core and on the ground, the first week of the Sabah election campaign has seen an ongoing blending of Malaysia’s old and new politics. Modern and traditional methods of campaigning coexist and are shaping the engagement with voters.

The media favour the "modern" style, the idealism and creativity of the "new", but among voters, the "old" reliance on personal connections, local influence with resources and social trust networks has considerable sway. Do not be fooled by what is on the surface of the campaign – empty ceramah for convicted "Bossku" and creative new songs and videos do not necessarily reflect the varied realities of how this campaign is being waged, and, ultimately, will be won.

Sabah has been the Borneo vanguard of new campaigning and strategies for some time. In GE14, millions of ringgit spent failed to deliver a BN victory – this traditional method failed. The mood for Warisan and "change" was strong in GE14. This time around the Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) partners have increased is game in its goal to take back power, recognising that Warisan Plus no longer has the same wind advantage. We see many different features of this campaign at odds with each other. Despite the media reports favouring Warisan’s messaging, the fight on the ground remains intense and close.

Unity vs divide and rule

The most covered campaign theme comes from the "Obam-apdal" poster. Warisan Plus is pushing a "unity" message. There are two dimensions to this unity message – one is along race and religion across Sabahans. The second is unity in Sabah leadership for the state.

The first aspect involving race is not as easy a narrative to sell as many would like to believe. Warisan faces persistent suspicions on the issue of illegal immigrants, especially among Kadazan Dusun Murut voters, and this issue remains prominent in the campaign in labels of candidates and underlying anxieties, regularly circulated on WhatsApp. One cannot underestimate long-standing appeals and emotions surrounding ethnic identity in Sabah.

In contrast, Warisan’s appeals to a "Sabah" identity vis-à-vis federal intervention and clear state leadership are stronger, especially among middle-class voters and in urban areas, who are concerned about the instability that a GRS majority could bring with unsettled leadership for the state. There are real worries that a divided GRS alliance will bring continued political uncertainty and undermine development in the state. Many voters are tired of Sabah being destabilised politically from "frogging" and personal ambition. None of the prominent GRS alternatives to Shafie have strong support publicly among more educated urban voters, especially Umno’s Bung Moktar Radin.

Equally relevant, is the continued issue involving state rights as resentments of federal encroachment, failure to deliver on the Malaysia Agreement of 1963 (MA63) and conflicting views of dependence on the federal government remain salient.

Umno, Bersatu, PBS and Star are opting more for a different non-unified approach –ethnic appeals. Their campaigns explicitly and at other times less openly appeal to race, in images, clothing and messaging. GRS campaigns speak more to the need for communities having a representative of a specific race or tribe and protector of this community. PBS and Star make strong appeals to Kadazan Dusun Murut nationalism, for example. Parties often use messages tied to religion, in some areas such as in the posters of the PN candidate in Membakut. These appeals are as much about empowerment for different groups as they are about displacement, tapping into both negative and positive conceptions of representation. Race and religion in Sabah remain important forms of mobilisation at the local level, used by all but disproportionately by GRS and the smaller parties. The "old" politics of race and religion is real and relevant.

There has also been a related strategic splitting of the vote along racial lines, with smaller parties and independent candidates part of this strategy. This is the long-honed tactic of divide and rule. In seat after seat, candidates have been fielded from one of the minority communities in a seat, quietly making an appeal along ethnic lines. The main parties field a candidate from the largest ethnic group, but smaller parties and independent candidates field an ethnic minority hoping to pull the ethnic vote. Some of the smaller parties and independent candidates are funded or supported in this "pull the vote" or "be the ethnic kingmaker/spoiler" strategy. BN has long used division of minority communities to stay in power in Sabah, a technique being used at the local level in this election by multiple players.

Persona vs personality

While the posters showcase the personas at the state and national level, there is tension with an emphasis on personalities at the local level. The prominence of local politicians with standing has long been a focus on traditional Sabah campaigns where personal loyalties are tied to family networks and social ties, while the centre has increasingly adopted more modern "presidential" campaigns.

We see both forms of engagement on the ground. PN is trying to build its reputation and capitalise on Muhyiddin’s popularity surrounding his government’s management of Covid-19 and distribution of taxpayer aid to taxpayers in need. That distribution of aid is framed as "giving" and the harsh reality of the dire need for the aid in Sabah is not really questioned. Instead, Muhyiddin is portrayed as a caring father looking out for the people, a traditional appeal to conservative patriarchal values reminiscent of older BN campaigns. Without fail, PN (aka from brother Umno) is following the tradition of concentrating on its leader – as the alliance does not have a clear local alternative it can promote.

At the same time, across political parties, there is a focus on the individual candidate. Disproportionately, most of the candidates are local, from communities. Smaller posters of individuals are the most in number in communities. Mobilisation of social ties builds on one of the most important factors in a Sabah campaign – machinery. Parties have weakened in recent years with splits and defections taking away machinery. This said, the ability to mobilise on the ground remains an essential part of the campaign, it is an integral part of traditional campaigning.

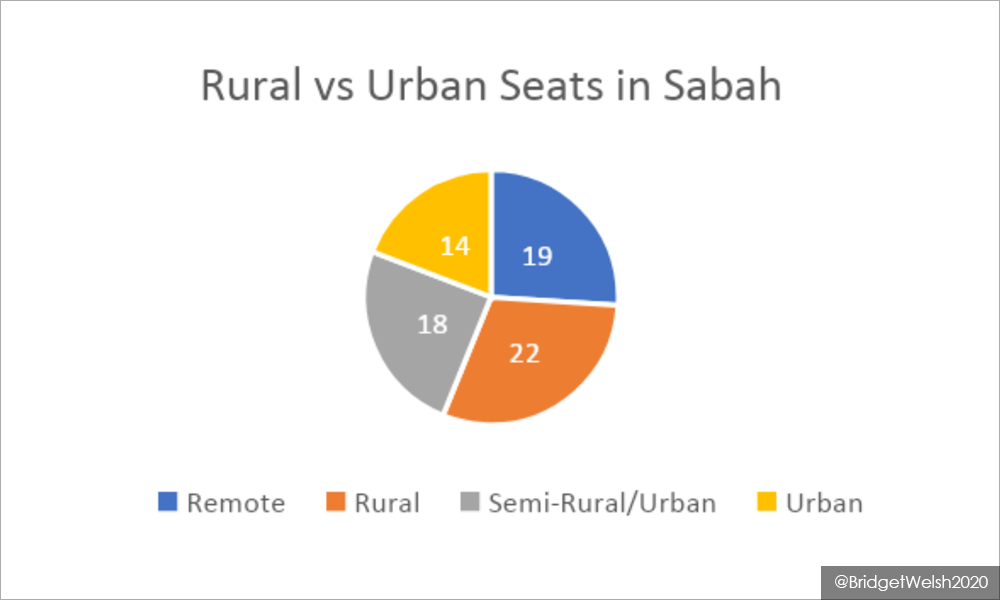

It matters most in places where more modern campaigns are not as effective – those with smaller populations and in rural areas. Few appreciate how rural Sabah is.

Below, based on being on the ground, I have divided the 73 seats into four categories, adding the "remote" category which reflects seats far from any small rural town, often lacking proper roads and Internet access. Only 19 percent or 14 seats are urban, compared to 26 percent or 19 seats in remote locations.

Getting to the voters involves resources and person power – an advantage that remains with BN/PN but has been somewhat reduced with Warisan Plus' role in the state government. The party machinery – as opposed to government machinery – is where sharp differences lie. GRS has longer and arguably stronger party ties in localities.

Motivational messaging vs money

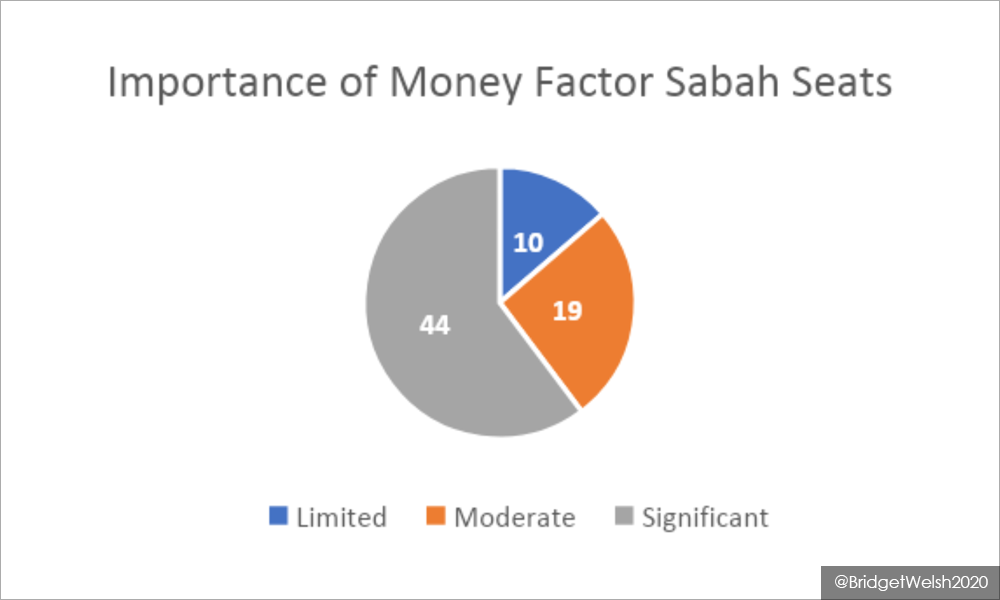

Warisan Plus thus has focused its campaign heavily on issue-based messaging, aiming to maintain (and even possibly increase) the levels of support it won in 2018. There are open appeals to idealism and the "Obam-apdal" campaign is appealing to similar chords of hope and harmony. All the contenders know, however, that what is essential in these rural seats is money. Money matters for the machinery, noted above, but it has long been an integral part of the campaign - used to offset the costs of transporting voters, gantirugi payments to voters who lose a day’s work for voting and ultimately used to confirm support, to get voters to come out and vote for a specific candidate or party – vote-buying. Poverty and vulnerability make the issue of money more significant in Sabah, but it is ultimately the parties who compete using this technique. The practice is well entrenched, creating expectations and demands. Amounts vary by locality and voter, but range from RM50-300 on average, sometimes higher to RM700-1,000, especially if this person is a local "influencer".

Money usually comes down heavily in the last few days of the Sabah campaign thought "bombing" but in this campaign, it is already flowing (there has indeed been lots of rain in Sabah and more expected). Negotiations are taking place with voters fielding offers. The funds are sometimes more than one family can make in a month. The intense level of competition this election adds to the money flow. Older campaigns were won on money. New modern campaigning relies less on money directly to voters, placing resources elsewhere. The test will be whether as in GE14 money bombs or whether bombing remains effective.

Above, again based on assessments of seats, I differentiate where money is seen as critical in the campaign. In some seats, parties competing against each other have limited resources, so money is used more selectively. In urban areas, campaigns rely on issues and more motivational issue-based messaging. Nevertheless, in over 60 percent of the seats money is a significant factor. It is used across the political parties with some candidates seen as more generous than others.

Friend vs enemy sabotage

If there is one tactic that is not adequately discussed to date in this campaign but extremely prominent, it is the role of sabotage. Friends are enemies and enemies are friends. Sure, this is done in a more friendly, less vicious attack form than can be found in Peninsular Malaysia but this practice of undercutting individuals from within is ongoing and common. It is highly personalised. Sabotage played a big role in the losses of Sabah BN in GE14. In a state where personal ambitions and competition are so open, the resentments are also open as well. Some supporters resent the candidate selection process. Others just do not like the candidate or the party. This election, the technique is being used against Warisan, Upko and within GRS itself.

Three factors make the 2020 Sabah state election even more susceptible to "sabo". First, there are federal-based players who are supporting candidates and using the campaign to undercut those they do not like. This is the only election in town, and many have joined the party. Second, the races are close, thus making this factor more impactful. There is electoral power in channelling disgruntlement. Third, and the most important, is the competition within alliances, and to a lesser extent within parties. For GRS, the main competition is between Umno and Bersatu (although Star and PBS also have tensions). The Sabah election will shape the respective power of these two federal parties and both national and state levels. Muhyiddin made a strategic mistake by announcing Hajiji Noor as the GRS CM candidate, fueling sabo fire. So far, nationally in by-elections, Umno and Bersatu have been able to put aside differences for victory; this is much harder to do in so many contests in Sabah. For Warisan Plus, the challenge lies within parties and with the alliance partner PKR. There is simmering distrust and suspicion, as it is not yet clear that all the parties are on the same page, and fully supportive of Shafie’s leadership.

One week in, it may appear as if all is rather quiet on the Sabah front. Do not be fooled. The campaigning is in full swing, but largely taking place in houses, in party offices, in personalised connections, through avid attention to smartphones (especially WhatsApp) and well beyond the posters. Sabah has its own blend of old and new campaigning. The election will test how effective older techniques of division, sabotage and money work. All sides are adopting a blend as they try to achieve success in a campaign that remains too close to call.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre. She tweets at @dririshsea. - Mkini

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.