Sabah's campaign for state polls starts in a few days. This state election will shape not only Sabah's politics but will be the first genuinely competitive contest for Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin's Perikatan Nasional government.

Neither of the previous Chini nor Slim by-elections were real contests; PAS and Umno put aside their differences and made good showings over weaker contenders.

The outcome of the upcoming Sabah polls, in comparison, will set Malaysia's political trajectory ahead – the timing of national polls, leadership battles, the strength of the Borneo state rights movements, and voter (dis)engagement, to name just a few of the issues.

Even if the results end up around the same as they were in GE14 - a tie - how the process evolves through alliances, the campaign, post-election and the splits in voting and outlook will be revealing.

The next three weeks – including the days after the election – will bring attention to the complexities of Sabah politics and showcase how Sabah and Malaysia's politics are (and are not) changing.

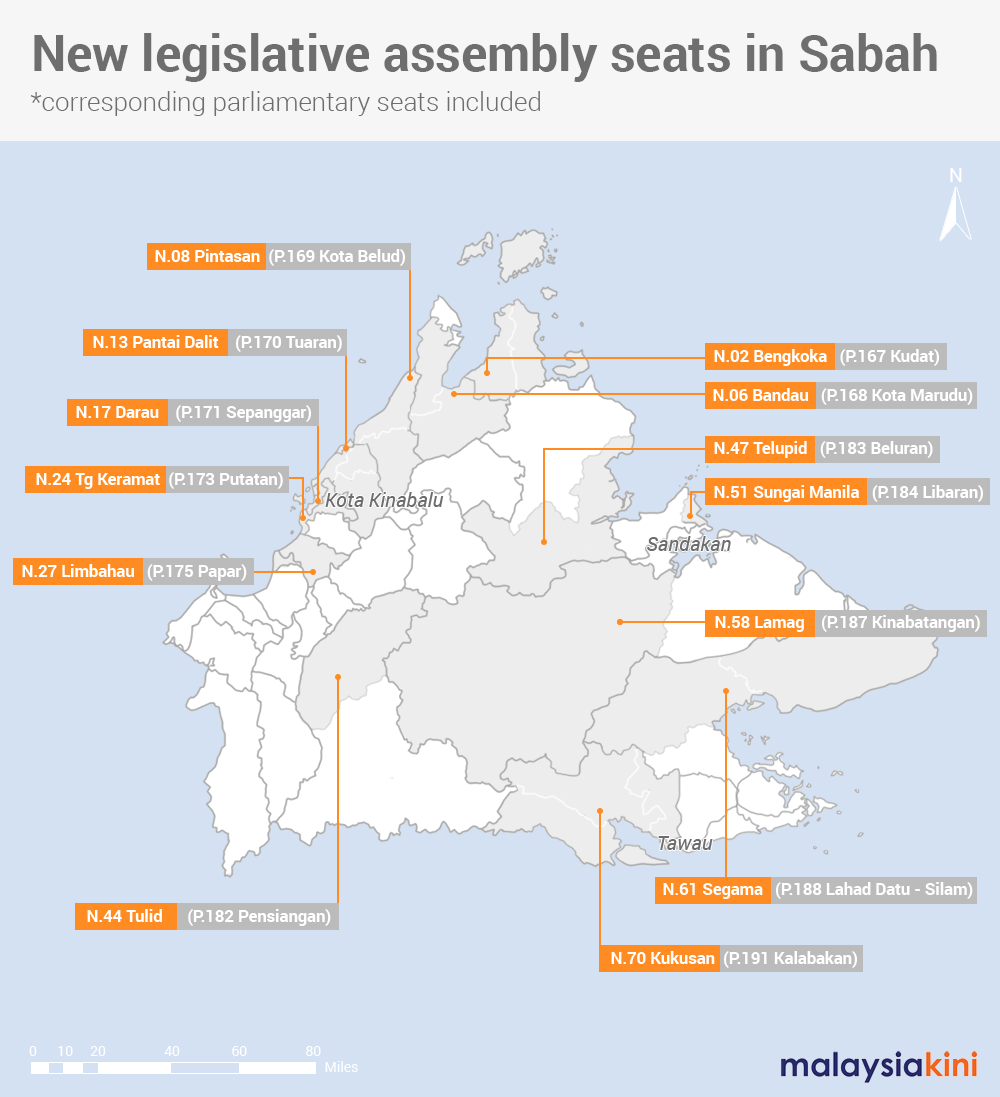

In my first piece on the Sabah 2020 polls, I am looking at the 13 new seats that were added in June 2019 and will discuss what these seats and the latest delineation exercise more broadly mean politically for the upcoming state polls.

An earlier Malaysiakini analysis by Ng Xiang Yi and Andrew Ong argued that they favoured BN, drawing from assessments of voting behaviour in 2018 in the respective polling stations that comprise these new seats. This was a good start. I would like to push the analysis a bit further.

Serious Electoral Carve

Foremost, in looking at the new seats, it is important to assess the picture holistically. The 13 seats were taken from other seats, changing the original configurations and possibly their political fortunes. A total of 27 seats from the original 60 were affected, almost half of all seats in Sabah at that time.

Table 1 details the seats affected and shows the share of the respective seat that now makes up the new seats, highlighted in yellow, and we see significant changes across Sabah.

Packing and Cracking Sabah Style

Looking at the changes, the first question one asks is what was the rationale for the changes. The short answer is political interest, but the long answer is more complicated.

Sabah's politics are complicated, and there are many different factors at play – often at odds with each other. One of the reasons the delineation was delayed – originally slated for 2016 and later pushed back due to resistance from the then Sabah state government led then by Musa Aman (then of Umno) – was that the new seats increased electoral competitiveness.

This contributed to why the delineation exercise was not approved before GE14. Gazetting the changes was not a risk they were willing to take at the time. Warisan's Shafie Apdal's government had a different view and pushed for the new seats to be accepted. It may, in fact, have been a risky move.

What then was the different logic of the Sabah delineation exercise? There are broadly five drivers in how seats are cracking and others packed.

First, Sabah followed the model of Sarawak, creating new seats to accommodate the varied ethnic communities in the state. This practice in 2013 contributed to Sarawak winning a larger majority in their own state election in 2016, as more of the smaller ethnic communities were recognised and allowed representation.

It favoured the governing coalition with its advantage in holding multiple seats that it could share and allocate seats more widely across communities.

Traditionally, the BN coalition with its broad umbrella has seen to be better positioned to accommodate more different ethnic communities. This is no longer the case, as not only has the coalition eroded in its ability to accommodate non-Malay dominant minorities, but other alliances - notably Warisan Plus - are competing against it.

Nevertheless, this "bring diversity into the umbrella" assumption underscored greater accommodation of ethnic minorities. We see, for example, a seat created with a majority of Iranun in Pitasan and Bugis and Tidung in Sebatik and Kukusan.

It is not always just smaller minorities. For example, in Papar, the new seat of Limabahau was carved out with a majority of Kadazan and Dusun, addressing the sense of displacement this community felt in this part of the state which has a long connection to these indigenous people along the Papar River.

Ethnic considerations overlap with religion. This is not so straight forward in Sabah as it is dichotomised in Peninsular Malaysia. Many of the Dusun indigenous people are Muslim, thus the labelling as "Muslim" and "non-Muslim" bumiputera.

In reality, families in Sabah often have both, but the classification labels show the federal way of thinking, prioritising religious difference. The trend has been to create more Muslim majority seats, as occurs for example with the changes surrounding Telupid and Labuk in Sabah's interior.

Labuk has become not only a majority seat for the Orang Sungai, but also a majority Muslim seat. Behind this are assumptions – not always correct assumptions – that this will favour BN or PN.

This feeds into sensitive issues about faith and displacement, not easy issues across Malaysia and also salient in Sabah politics despite the state's more harmonious inter-ethnic and inter-religious relations.

At the same time, a third practice is to create ethnically mixed seats and follow the older model honed in the 1980s under the first Mahathir period, to reduce risk, to split votes and loyalties. We see this in the new seats of Pantai Dalit, Segama and Darau, for example. Old practices meld with new practices, as history has shown that a reliance on one rationale is risky.

We see also packing of seats to contain the support of particular parties. For example, more Chinese voters were moved into the urban seat of Luyang won by DAP, taken from Kapayan, making the latter seat more competitive for DAP and for other parties that appeal to or rely on ethnic loyalties.

This replicated what happened in Peninsular Malaysia, where large numbers of voters were packed into DAP seats in a strategy of "containment".

Finally, and perhaps most obvious, is serving the dominant incumbents and parties. Musa Aman's Sungai Sibuga seat was split, creating two seats with the addition of Sungai Manila. Speculation surrounded which (and whether) he will contest, the traditional seat or the newly prepared one. Musa announced today the new one, Sungai Manila.

In similar former incumbent Umno's heartland of Bung Mokhtar Radin, the new seat of Lamag was created, with a small number of 8,159 to win over. He has publicly confirmed he will contest in the seat. Lamag is very rural and remote, as is Tulid and to a lesser extent Telupid as it is along a main road – but they all share low numbers of voters, making them easier to compete in and win.

Ethnic accommodation, changing ethnic composition of seats, ethnic splitting, containment and incumbent empowerment are combined as part of Sabah's unique cracking and packing style in its delineation.

Increased competitiveness

One may now ask what the political consequences are? What does this mean for the state's politics?

To start, one implication is money, taxpayer money. Each of these new seats gets allocations from public funds. The assumption is that these funds will be shared with the community and enrich representation.

Sadly, this is not always the case. Increasing the number of politicians does not increase the quality of representation.

Secondly, is the effect on the equality of representation in Sabah. While smaller ethnic communities are being accommodated, others are not. Disproportionately, many indigenous communities are being given greater influence in many seats, especially if they are Muslim.

These issues raise questions about how power is distributed with understandable sensitivities and tensions. The vision of Sabah promoted by the federal government is quite different than that seen locally within the state.

The new seats do add to the malapportionment within Sabah as some Sabahan voters have more voting clout in the smaller seats than others. Comparatively, Sabah is less imbalanced as some other states in Malaysia, but there is inequality.

Voters on the island of Banggi, 5,961 of them, certainly have more influence per voter than the 30,034 in Kapayan, by a ratio of 5:1. Most of the new seats, however, are around the average of 15,000 voters in a seat.

Thirdly is the effect on political parties/alliances. Here, new seats create opportunities, reducing pressures on alliances as they provide new seats to bargain and distribute.

Given that it is now three days before nomination day and the candidate lists for the various alliances have not been announced, there are most certainly intensive negotiations going on, with the new seats a core part of the discussion.

Lucky Thirteen?

Finally, to the issue of political chances and which side(s) does the delineation favour?

To see Sabah's competition as binary – Warisan Plus versus PN/BN/PBS/STAR/Third Forces is too narrow. Allegiances are fluid, and it remains to be seen whether there will be straight fights, multi-cornered fights or multi-multi cornered fights.

Of the thirteen seats, two have clear advantages for traditional incumbent forces in the area – Sungai Manila and Lamag. The others are competitive, with candidate factors and different types of contests shaping the competition.

The tendency is to project voting patterns of GE14 on the future Sabah polls, and this also needs to be reassessed as Sabahans do swing their votes and loyalties are shifting. By how much it is still not fully clear as the campaign is starting and will matter.

Who will be (un)lucky from the thirteen remains to be seen.

Sabah's thirteen new seats have added to the competitiveness, and in some ways fueled resentments and in others addressed resentments.

They certainly will make the election more costly, especially in seats where political funds play a large role, and more interesting. There is a lot to watch and learn as the election evolves.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre. She currently is an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. She tweets at @dririshsea. - Mkini

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.