KINIGUIDE | The Umno supreme council unanimously decided last week that it would apply for a pardon for Najib Abdul Razak.

This is the second royal pardon bid in seven months to provide an early release for the former prime minister, who is serving a 12-year jail term over corruption in the SRC International case.

In this instalment of KiniGuide, we look into the key areas of a royal pardon process and how it applies to Najib's case.

What is a royal pardon?

A royal pardon is an official order by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to stop the punishment of a person accused of a crime.

Pardons are usually sought after a prisoner has exhausted all their legal remedies in court.

There are two types of pardons: a “conditional pardon”, where the sentence is substituted with a lesser sentence; or a “free pardon” which purges the prisoner’s offence and all consequences of their crime.

Based on Article 42(1) of the Federal Constitution, the Agong’s power to grant a pardon is limited to offences tried or committed in the Federal Territories - Kuala Lumpur, Labuan, and Putrajaya.

Clemency for offences committed or tried in other states would be in the hands of each state’s Malay ruler.

The Agong will grant the pardon upon the advice of the Pardons Board.

Can Umno file a pardon on Najib’s behalf?

Under Article 42 of the Federal Constitution, all convicted prisoners are entitled to apply for a pardon.

Najib himself applied for a royal pardon in September last year, after he was convicted.

On March 31, the Federal Court dismissed his application to review his conviction and sentencing in the RM42 million SRC International corruption case with a majority 4-1 verdict.

The following week, Umno supreme council unanimously decided to seek a royal pardon for the former premier.

The council will also present to the monarch a memorandum signed by all 191 Umno division leaders.

Najib’s lead counsel Muhammad Shafee Abdullah said he would use the dissenting judgment of Federal Court judge Abdul Rahman Sebli to support the pardon application.

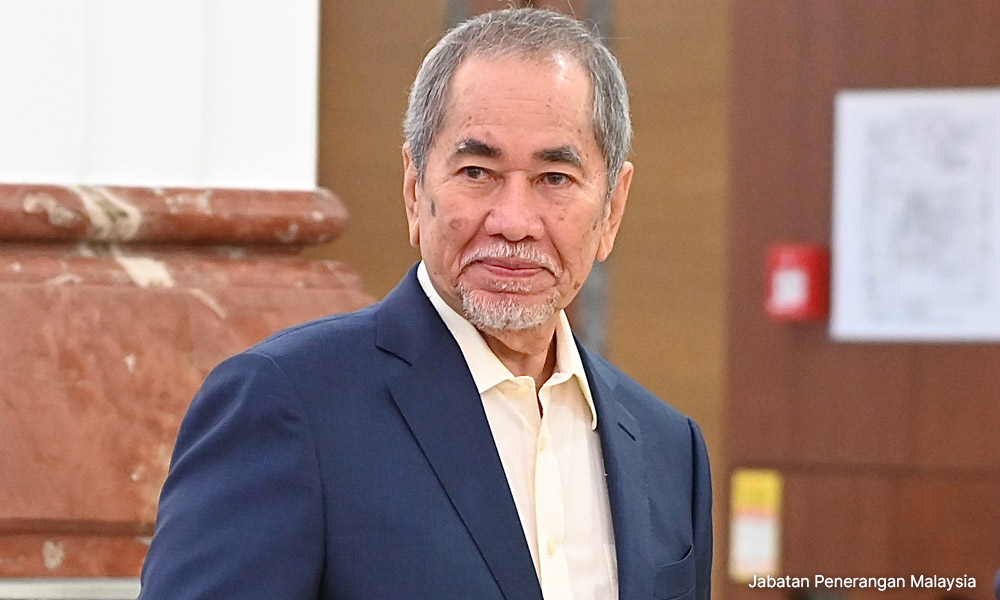

However, lawyer Mohamed Haniff Khatri Abdulla and former law minister Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar have both opined that Umno cannot file a royal pardon application on Najib's behalf.

This is because, under Regulation 113 of the Prison Regulations 2000, a petition can only be filed by the convicted, their family or a lawyer appointed by them, and the Prisons Department.

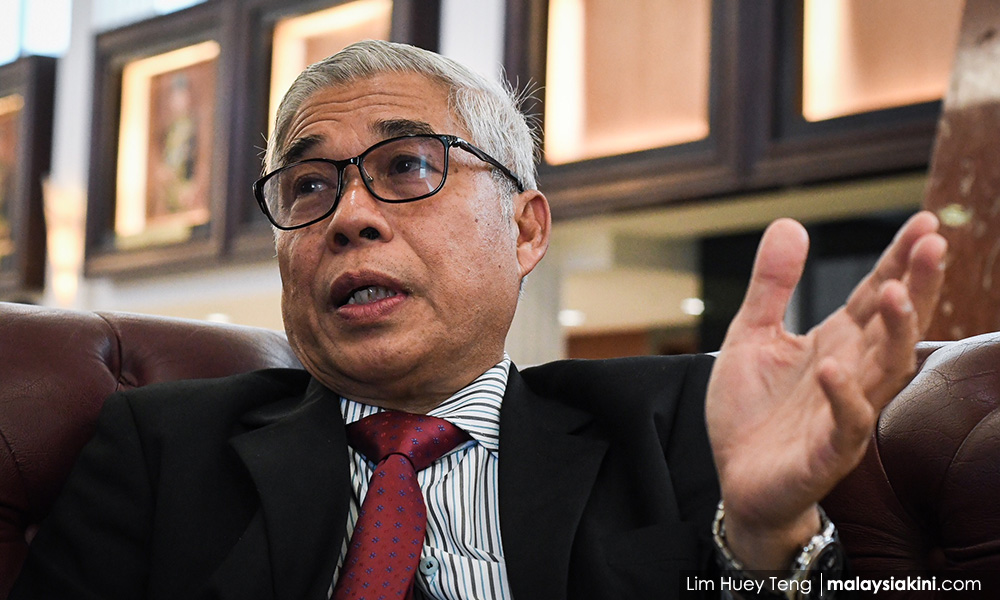

Haniff said that Umno can only file a letter or petition of support to the Agong.

Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform) Azalina Othman Said responded that Umno was no longer involved in the pardon process and that the decision was now up to the Agong.

What are the criteria to seek pardon?

According to former attorney-general Tommy Thomas, the first criterion is that the prisoner must have served one-third of their jail sentence before applying for a pardon.

He noted, however, that this was not a legal requirement but a convention, based on a process built over decades since Merdeka in 1957.

According to Regulation 113 of the Prisons Regulations 2000, a prisoner may send a petition seeking clemency “as soon as practicable” after their conviction.

The second petition is allowed when the person has completed three years from the date of conviction. Any further petitions shall be granted at two yearly intervals unless there are special circumstances.

Thomas argued that this raises practical issues due to the large volume of prisoners in the jail system. He added that Najib should "wait his turn".

Thomas said that the second criterion was for the prisoner to be able to show evidence that they have reformed - which would take roughly three or four years.

“All convicts would say that they have reformed. The convict’s statement carries no weight because it is self-serving.

“So it is always backed by the parole officer, prison officer, hospital people, and many other independent sources. The more references you get, the better your case. All the references must point to the fact that you have reformed,” he added.

The third criterion, he said, is that the prisoner cannot have other pending criminal cases.

Najib has three more cases, including the RM2.28 billion 1MDB corruption case which is still undergoing trial.

The other two that have yet to go to full trial are the RM27 million SRC International money laundering case and the RM6.6 billion International Petroleum Investment Company (Ipic) criminal breach of trust case.

What happens after the petition is filed?

There are no actual guidelines or regulations regarding the process of seeking a royal pardon.

According to Thomas, the Pardons Board meets three to four times a year and considers about 10 applications per sitting.

The Federal Territories Pardons Board consists of the attorney-general, the Federal Territories minister, and three members appointed by the Agong, who will chair the meetings.

The Prisons Board is required to consider any written opinion given by the AG before tendering advice to the Agong.

Legally, there is no time limit for the Agong to decide when to grant a pardon.

Do we have a Federal Territories minister?

No, we do not. The responsibilities of the Federal Territories Ministry are placed under the Prime Minister’s Department.

By virtue, Anwar is a member of the Pardons Board by being the de facto minister of the Federal Territories.

He confirmed his involvement on April 8 that he would be part of Najib’s royal pardon process.

However, he dispelled rumours that it would result in any conflict of interest as the final decision rests on the Agong.

Major concerns were raised surrounding Anwar’s involvement in the Pardons Board. Wan Junaidi, however, said that the AG would play a bigger role than the prime minister.

“The granting of a royal pardon is not within the scope of the administration or the executive.

"As such, in the matter of an application for a pardon, the AG will provide his legal opinion and advice from the AG's Chambers.

"However, even with the advice, the Agong has the absolute authority to decide on his own whether he wishes to issue a pardon or otherwise,” he was quoted as saying by New Straits Times.

Is the Agong required to follow the advice of the board?

There is a large discourse on this.

Article 42(4) and Article 40(4)(a) of the Federal Constitution does indicate that the Agong has to act upon the advice of the Pardons Board.

However, the Supreme Court ruled in Sim Kie Chon v Superintendent of Pudu Prison & Ors (1985) that it was not mandatory for the Agong to act on the advice of the Pardons Board.

The Supreme Court asserted that the role of the Pardons Board was to only provide advice to the Agong.

Pasir Gudang MP Hassan Karim, who is also a lawyer, claimed that his reading of Article 42(1) and Article 42(5) of the Federal Constitution meant that granting pardons was the Agong’s sole prerogative.

Anwar’s former lawyer Zainur Zakaria, however, differed, saying that Hassan’s claim was incorrect as the king has to act based on the Pardons Board's advice.

Can Agong’s decision be challenged?

Article 32(1) of the Federal Constitution states that the Agong shall not be liable to proceedings in court.

However, the justiciability of the Agong’s decision had been raised in 1986 in Superintendent of Pudu Prison & Ors v Sim Kie Chon.

Sim had claimed that the Pardons Board was void and legally ineffective after the Agong had rejected his plea for clemency.

The Supreme Court took the view that Sim was attempting to challenge the exercise of the Agong’s powers of clemency under Article 42 of the Federal Constitution.

The Federal Court also ruled in the case of Juraimi bin Husin v Pardons Board, State of Pahang & Ors (2002) that the prerogative of mercy, which includes the power to grant a royal pardon, was not liable to judicial review due to its nature and subject matter. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.