Chong Keat Aun’s “Snow in Midsummer” is a poignant and haunting exploration of one of Malaysia’s darkest historical episodes, the May 13 riots of 1969.

The film transcends mere historical recounting, instead delving deeply into the inter-generational trauma and the lingering wounds that continue to affect Malaysian society.

It is a masterful piece of work that not only honours the memory of those affected but also underscores the urgent need for truth, reconciliation, and the healing the nation desperately needs.

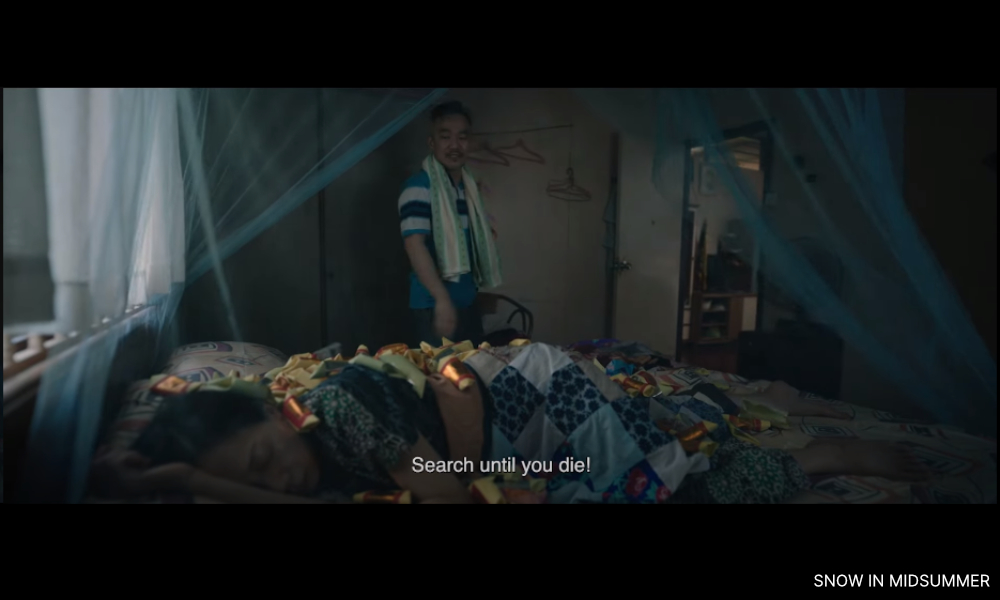

“Snow in Midsummer” follows the intertwined stories of several families, each grappling with the inherited grief and unresolved questions stemming from the May 13 tragedy.

The film opens with a series of evocative images - a tapestry of cultural symbols, personal relics, and archival footage - immediately immersing the audience in a world where the past is ever-present.

The narrative is meticulously constructed, weaving together personal testimonies and historical documentation. Chong spent more than 10 years collecting oral histories from those who visited Sungai Buloh cemetery where the May 13 victims are buried.

This approach allows Chong to present a multifaceted perspective on the events of May 13, moving beyond simplistic explanations and offering a nuanced understanding of the conflict’s root causes and its enduring impact.

Powerful use of metaphors

Chong’s direction is both sensitive and incisive. He employs a lyrical visual style, using stark contrasts of light and shadow to reflect the film’s themes of memory and loss.

Snow is of course an unusual and anachronistic element in tropical Malaysia - the opera troupe happened to be performing the old classic “June Snow” in 1969. It serves as a powerful symbol of purity and erasure, a reminder of the cold, unresolved emotions that lie beneath the surface of the nation’s history.

The film’s use of powerful metaphors, such as the raja on his elephant striding through deserted Pudu, adds layers of meaning and resonance to the narrative.

This image is evocative of traditional authority and power, yet its presence in an empty, desolate landscape suggests the futility and isolation of unchecked dominance.

The deserted streets of Pudu symbolise the aftermath of conflict, where once-vibrant communities are left in ruins, and the imposing figure of the raja on his elephant underscores the themes of control and historical legacy that continue to influence contemporary Malaysia.

The spectre of ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy) from the legends of the Malay Annals is another potent metaphor that Chong skilfully incorporates into the film. The invocation of these legends within the context of the film highlights the tension between mythic grandeur and the harsh realities of modern political and social life.

It suggests that the spectre of dominance, like a haunting presence from the past, continues to loom over the nation’s collective consciousness, influencing perceptions and actions in ways that are often subconscious and deeply ingrained.

Reflection and healing

What sets “Snow in Midsummer” apart is its unflinching examination of the need for closure and the search for truth. Chong does not shy away from the difficult questions or the uncomfortable truths.

Instead, he invites the audience to engage in a collective process of reflection and healing. The film’s climax, a cathartic and emotionally charged ceremony at Sungai Buloh cemetery is a testament to the power of acknowledging and confronting past injustices.

For me, “Snow in Midsummer” is more than just a film; it is a call to action. It urges Malaysians to confront their shared history with honesty and compassion, to seek out the stories that have been buried, and to honour the memories of those who suffered.

By doing so, the film suggests, the nation can move towards a more just and inclusive future.

The film addresses the lingering trauma of May 13 with grace and courage. It demands to be seen, discussed, and remembered, for it holds the key to the long-anticipated healing and reconciliation in the country.

Malaysians will be proud to know that “Snow in Midsummer” has won an award at the 2023 Venice International Film Festival, nine categories in the Golden Horse Awards, and four categories in the Hong Kong International Film Festival. - Mkini

KUA KIA SOONG is a human rights activist, former Suaram director, and former DAP MP.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.