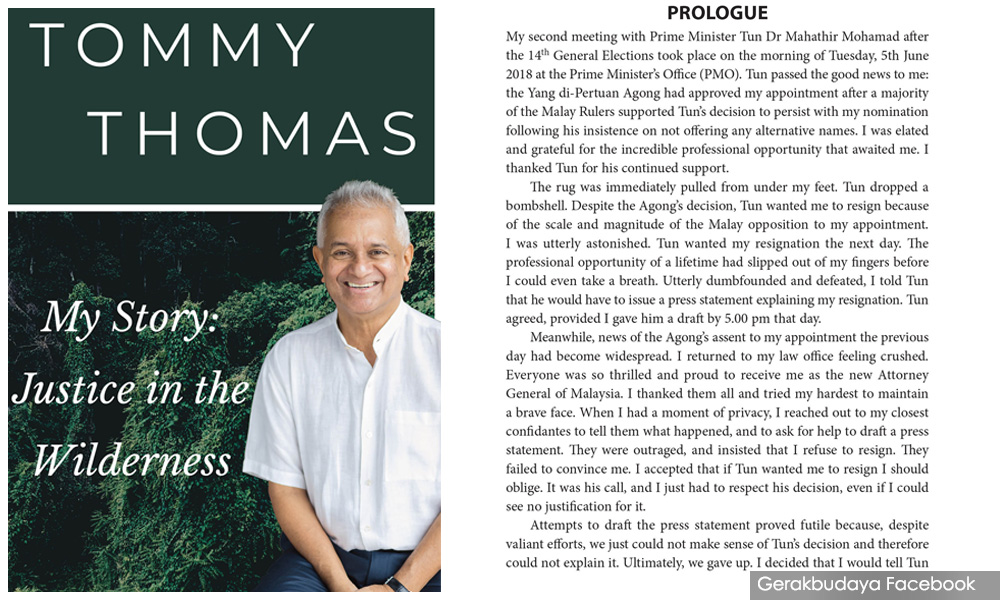

There’s a quote I found quite memorable in former attorney-general Tommy Thomas’ hotly-debated new book, “My Story: Justice in the Wilderness”, where the author defended himself against accusations that he spoke poor Malay by describing what he believed to be a key feature of the advanced complexity of common law:

“It is largely a result of the greatness of the English language, the language of Shakespeare, Milton, Dickens and Austen. Hence, it was not so much that one is reluctant to use Malay for legal purposes; it was rather a commentary on the greater benefits of English.”

Two other similar controversies recently emerged alongside Thomas’ quote that are also related to the politics of language in Malaysia - the first being an educational video clip by a teacher on human reproduction on the newly-launched DidikTV, and the second being a streamed speech (start at 47.40) given by Women, Family, and Community Development Minister Rina Harun.

The latter two were criticised - sometimes virulently - for representing a very poor standard of English in their respective presentations.

Language of course does not exist in a vacuum, and is closely tied to the fault lines of both ethnicity and class. Indeed, language barriers often mirror much more significant social barriers.

Many people with my background, class, and type of education often advocate teaching in English, sending their kids to international schools, and are quick to criticise public figures who do not have a good grasp of English. The arguments used publicly are often centred around the practical benefits of speaking what is probably the world’s most international language.

It’s probably fair to say that those who are most critical of others with poor English are people who themselves speak good English. These criticisms imply a certain expectation that the people criticised (like Rina Harun or the DidikTV teacher for example) should in fact have a better grasp of English.

If we take a step back from our assumptions, the question arises: why should we expect this of them?

If a minister from say Japan, China, Russia, France, Brazil, Mexico, Egypt, or Algeria could not speak English well, would we be angry about it? Are we thus angry because children in those countries do not learn English in school (I imagine some do), while ours theoretically do? Are we angry because we are a Commonwealth country? (Implying we are angry that our fellow citizens cannot speak the language of their colonial oppressors)

It is fair of course to say that educational programming that has decided to use English as a medium of instruction should employ a high standard of English.

But this is no reason to hit out strongly at the teacher being featured. Nor is it an excuse to slip into what is for some a frequent generalisation and denigration of civil servants and their command of English, and (sometimes subtly, sometimes not) an entire community and perceived levels of education.

With regards to the DidikTV case, instead of criticising the teacher, I think a more reasonable approach is to ask questions like: Why were presenting teachers not given sufficient resources and help to ensure the quality of their presentations? Why did the entire initiative seem poorly planned and rushed, even though the government should have been dealing with the pandemic and its effect on education for over a year now?

This controversy is obviously related to the question of whether science and mathematics should be taught in Malay or English. Maybe it is because I myself studied my entire curriculum in Malay, and don’t feel disadvantaged in any way from it, but I generally lean towards using the former.

The amount of effort required for so many teachers - like the one on DidikTV perhaps - to achieve the level of English ‘demanded’ by others seems to be an inefficient use of limited resources. If teachers are having a hard time of it, can you imagine how difficult it is for students who are even less exposed to English?

It is more important that the child is educated well, than the child is educated in an ‘international language’. Forcing education to be conducted in a language alien to both teacher and student will result in a reproduction of what we saw on DidikTV all throughout the country.

Tone deaf and insensitive

In Rina Harun’s case, I agree that she did not speak English well. But if I were to truly reflect on it, I am hard-pressed to believe that proficiency in English should be a primary metric in determining either someone’s suitability to be appointed minister, or their performance as minister. It certainly helps, and is an advantage, but it does not make a minister or potential minister either good or bad.

As a commentator, I cannot help but take this opportunity to go slightly off-topic and comment briefly on a few other controversies that this particular minister is involved in.

Rina was the subject of considerable attention when modelling-style photos of her emerged on the internet (alongside some articles in the press about them), in which she looked considerably different than before.

I get the feeling that had she been a more popular figure, it is possible that these pictures may have been more warmly received.

In any case, from a communications perspective, I think it is important to note that allowing such pictures and coverage to emerge at a time when a great number of Malaysians (not least the women and children that she is supposed to be watching out for) are suffering greatly due to a pandemic is the epitome of being tone deaf and insensitive. The backlash can hardly be considered surprising.

We must definitely avoid this terrible tendency to let discussions about how a woman looks dominate discourse - just as it is not particularly productive to make fun of how she speaks English. It is probably fair however, to question whether or not a minister has her priorities straight, and is spending her time on things that matter.

The recent controversy over how exactly she could have afforded to pay off a seven-digit debt should of course also be examined.

This brings us back to Thomas. Before continuing, I must say I believe that any crackdown by the authorities on Thomas or his publishers is completely unwarranted.

My last article concerning his book spoke at some length about this quote: “I could not find an AGC officer of sufficient experience, expertise, with the ability to work independently and to lead the preparation in my absence.”

I don’t think we can be blamed for thinking there might be some arrogance in this statement. In addition to the first quote above, Thomas also wrote the following:

“Referring to English, all the lawyers and staff in the Attorney General's Chambers, from the moment of my arrival until my retirement, went out of their way to converse with me in English. Even the duty policeman who greeted me every morning at the entrance, and on the 16th floor spoke to me in English. So did the cleaners.

“All the draft opinions, letters and memoranda prepared by the Attorney General's Chambers for my attention were in English. All our discussions were conducted in English. I am most grateful to everyone in the Attorney General's Chambers who made my tenure in chambers most satisfying as far as the use of English was concerned. Never once did I face any unhappiness, let alone hostility, from an Attorney General's Chambers' officer or staff member because of my poor command of the Malay language.”

No reader should presume to always know an author’s intent. In terms of interpreting the above, I suppose there are two ends of the spectrum - and I would not deign to know which is more accurate.

The kinder interpretation is of course that Thomas was merely praising the high standard of English of people in his office. A slightly less kind interpretation is that Thomas is proud of the fact that his subordinates all had to defer to him and speak to him using the colonial language that he preferred.

Superiority complex

I am not some rabid anti-colonial who hates all things British or English, or one who likes to rant and rave using the word ‘colonial’ in every other sentence. There’s no reason to be. But attitudes like these about language are subtly akin to exactly the kind of superiority complex that colonial powers exuded - all part and parcel of the myth of the lazy native.

I think it is not unreasonable to say that for many, the use of the phrase “the language of Shakespeare, Milton, Dickens and Austen” here is also a little cringey.

Again, while not being supportive of unbridled cancel culture and so on, I think we cannot be blamed for reading a certain subtext here - citing (only) great English authors in the context of comparing one language to another surely implies (to an extent at least) that the language to which it is being compared lacks such literary heritage and sophistication.

Just because the author is likely not well-versed in the titans of Malay literature does not mean such titans do not exist.

I contend that there are towering Malay writers - not just in the past, but living and breathing among us - writers skilled in dancing gracefully in and with a language that is richer and more nuanced than most English speakers who often shun or look down on Malay can appreciate.

The fact that the four English authors quoted have more name recognition than say Usman Awang, Muhammad Haji Salleh, Zurinah Hassan, or Siti Zainon Ismail likely has more to do with both physical and cultural imperialism than with literary quality and value.

In commenting on this topic, it is worth saying that discrimination in the other direction is also equally unhelpful. There are times when people are disliked or automatically assumed to be arrogant simply because they are speaking in English. Such emotional kneejerk reactions contribute equally to social division.

Perhaps what is most important to remember ultimately is that no language is ‘superior’ to another. Some of us have a tendency to judge and evaluate people differently based on which languages they speak, or think that we are somehow ‘better’ because we speak a language that has more economic value internationally.

These kinds of thinking tend to drive even deeper wedges between our already divided society.

When I went to school, a very high number of non-Malays still attended government schools or did the government syllabus. That number has dwindled over the years, and with it, the number of non-Malays who are comfortable speaking Malay. This also reflects some attitudes that think of Malay as a ‘useless’ language.

I really hope this trend can be reversed, as a widely spoken lingua franca is such a key element of nation-building. I believe the right way to do so should involve less forcing or high handedness, but an emphasis on the beauty of the language, and its importance in forging a true #BangsaMalaysia.

NATHANIEL TAN was greatly encouraged by the outpouring of support for Malaysiakini and their great work. Twitter: @NatAsasi, Clubhouse: @Nathaniel_Tan, Email: nat@engage.my. - Mkini

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.