DEFORESTATION INC | In 2019, signs of logging appeared near Kampung Lawai, an Orang Asli village located in Jalong Tinggi, Perak.

Kampung Lawai is the highest among the several Orang Asli villages in that area, with an altitude of more than 635m.

Heavy machinery was brought up the mountain, causing damage to the roads and polluting Sungai Korbu, the main water source for the villagers.

Landslides are one of the concerns among the locals about the safety of their homes in case of heavy rain.

Furthermore, the logging plan also caused a conflict among the villagers.

Mat Seri Pandak, a resident of Kampung Lawai, told Malaysiakini that the developer had tried to bribe the villagers with money to prevent them from protesting.

However, some villagers returned the money to MACC and proceeded to lodge a police report.

The one-off "compensation" could not solve the long-term impact of logging on the Orang Asli community's livelihood.

Mat Seri said some young Orang Asli had previously planned to work on ecotourism, bringing interested tourists to experience nature on low-impact tours.

However, the logging plan not only destroyed the landscape but also damaged the forest trails, making it difficult for outsiders to enter.

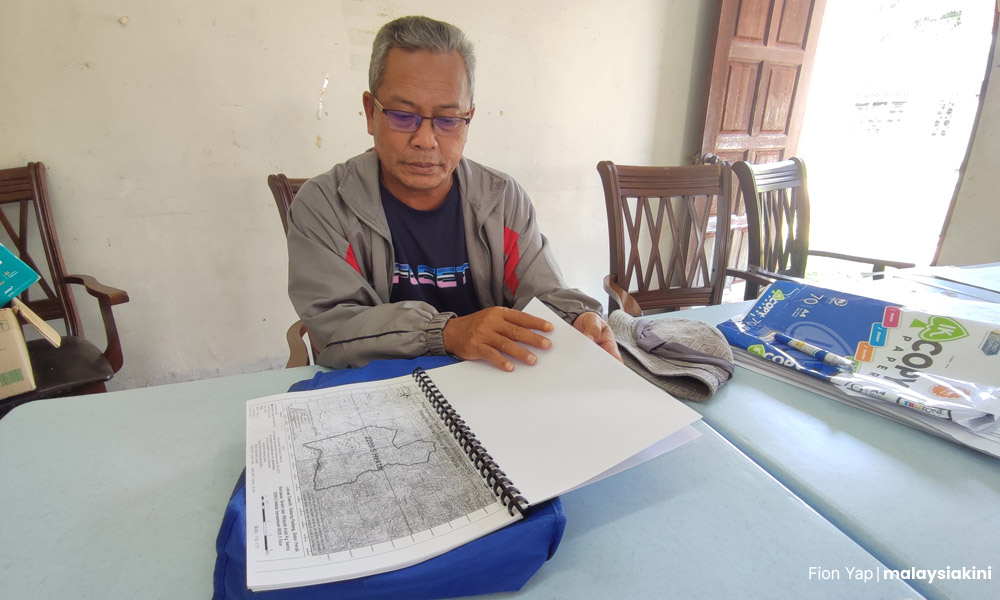

Although the issue has been resolved, the memory is still fresh for Mat Seri.

"From that, I saw how rich and smart people incited the villagers to fight with each other and break up over money," he said.

Today, the logging plan has been suspended due to protests by the residents and the following movement control order (MCO) due to the Covid-19 pandemic. During this period, permits for selective logging expired for particular compartments. But for other compartments, selective logging will likely start again after a cycle is completed, much to villagers’ concern.

Certification as solution to conflict?

With an export value of RM25 billion in 2022, timber is a significant contributor to the Malaysian economy. But since the 1990s, there has been ongoing friction between the indigenous community and the logging industry, particularly in Sarawak where vast tropical rainforests are concentrated.

Over the years, multiple blockades have been set up by indigenous people, in an attempt to stop logging companies – some lead to physical conflicts.

The Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS) was established under the Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC), in response to this situation.

It was expected to provide a sustainable management approach to the logging industry, so its practices are environmentally sustainable and protect the rights of the indigenous community.

But whether it has met this mark remains a question.

How MTCS works

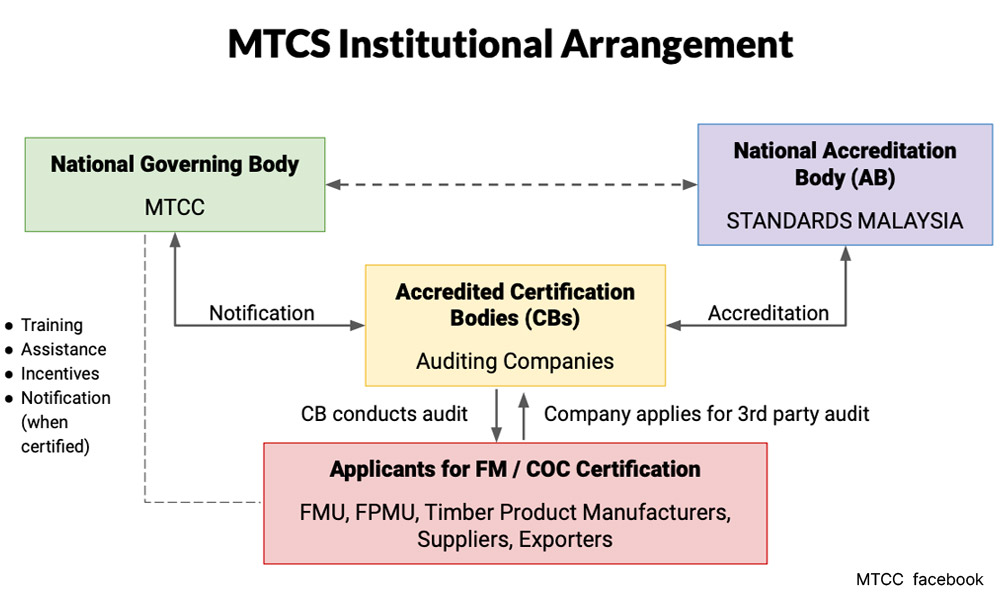

The MTCS is an independent and voluntary certification scheme under MTCC. At the international level, it is recognised by the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes (PEFC).

There are two levels of MTCS certification. The Forest Management Unit (FMU) certification is at the upstream level and deals with the extraction of timber and the downstream certification - Chain of Custody (COC), which monitors the processing of timber and its products all the way to export.

In Peninsular Malaysia, the FMU certification is issued to forestry departments that manage the extraction of timber. In Sabah and Sarawak, they are issued to forestry companies. The Perak Forestry Department holds an MTCS certification, and by right, all selective logging activities in the state - including near Mat Seri’s village - should adhere to MTCS standards.

Protection of Orang Asli rights

Besides limits to forest conversions and protection of ecologically sensitive areas, upholding indigenous community rights is a key criterion for MTCS certification.

Certificate holders must prove that they respect the rights of the natives to own, use and manage the land in the forest, unless they delegate the control to others, with free, prior knowledge and consent (FPIC).To do this, they must engage with the indigenous community before forestry activities are started, and conduct a social impact assessment to ensure activities do not affect the communities’ way of life or livelihood.

If there is a risk of infringing on this, the community must provide prior consent and compensation provided. Timber products which are involved in disputes over indigenous land rights are also categorised as “disputed resources” under the COC standards.

Compliance is checked through audits by MTCS-appointed certification bodies through scheduled and unscheduled audits.

MTCS’ standard was developed by a team comprising indigenous representatives from the Peninsular and East Malaysia, as well as stakeholders such as the director of the Orang Asli Development Department (Jakoa).

The guidelines are reviewed every five years. On paper, it looks perfect.

Different on the ground

However, indigenous people interviewed by Malaysiakini have little knowledge of this, were unclear of grievance processes or did not trust MTCS.

Kampung Chang Lama is another Orang Asli village in Bidor, Perak, still suffering from logging activities since decades ago.

After unusually heavy rain in April and May last year, local rivers remained murky until February this year.

Kampung Chang Lama is only 5km from the city centre of Bidor, but half of the villagers' homes have no access to running water.

After the river water was polluted by runoff from logging and a pig farm, some villagers had to borrow water from their neighbours or walk to more distant rivers to obtain water.

“So, what’s the benefit of logging to our community?” asked a villager, Rizuan Tempek.

He is among the few Orang Asli villagers who have knowledge of MTCS. In 2011, he went to the Netherlands to participate in a parliamentary hearing, where he called out the MTCS-certified timber as “unsustainable".

Rizuan believes these certification standards may look good on paper, but the execution is weak and no one is supervising it properly.

He said the engagement process with the Orang Asli is poor and even if done, alienated the villagers who either do not understand English or the academic terms used.

"They invited the Orang Asli, but not many could understand. They are just discussing their business, and everyone will agree with the agenda.

“We attend not to support, but to listen. However, after we attend, if no one opposes or speaks out, we are considered as the Orang Asli representatives who agreed with the agenda," said Rizuan.

Not fully consulted

Mat Seri Pandak of Kampung Lawai is also aware of the MTCS, and that Sirim QAS International is the auditor for MTCS in Perak. But he does not really understand the auditor’s role.

He recalls officers visiting the village to seek consent for the logging projects, but they only met with villagers who he said were aligned with developers and sought signatures from the village head alone.

"The certification standards might be in good intentions, but in practice, they merely collected the opinions of some villagers.

“If they agree, they record it. For our rejection, they would just listen to it and ignore it," Mat Seri said.

However, Rizuan and Mat Seri said they have never directly dealt with MTCS or its auditors.

This is perhaps not surprising.

According to MTCS guidelines, the auditor only needs to interview village heads and 10 percent of the households in a forest management unit.

The villagers are selected at random, using a provided formula, but feedback from the villagers suggests this might not always be the case.

Who should the community complain to?

The MTCS’ complex decentralised structure also makes the dispute resolution process unclear to stakeholders. The MTCS itself can only handle disputes over the standards, but not the application of the standards.

Such disputes are dealt with by certification bodies, who conduct the audits. The certification bodies are accredited and monitored by Standards Malaysia, a department under the Science, Technology and Innovation Ministry.

MTCC representatives met with Malaysiakini for an interview but declined to be identified by name. They likened the MTCS to lawmakers in Parliament. When a law is broken, one representative said, the complainant does not complain to MPs or Parliament but reports the crime to the police.

In this analogy, the “police” are the auditors or certification bodies, like Sirim QAS International. And if the stakeholders believe the auditing process was unfair or improper, they can complain to Standards Malaysia.

"They can still come to us, but our role is not the 'police' here, so we will pass the complaint to the auditor or Standard Malaysia, depending on who the complaint is for,” he said.

He acknowledged that cases against auditors were the main category of complaints received by MTCS, but mostly from companies who complain that the auditors are too strict. Very few are received from the community stakeholders.

‘Not like SPM - 100pct compliance required’

To obtain MTCS certification, the state forestry department or forestry company will apply to the auditor, Sirim, which then reviews the forest managers’ practices, for a fee.

The certification is also issued by Sirim, while MTCS does not receive any payment. Instead, the scheme, run under the MTCC, is funded by a government grant.

"It's not like taking the SPM, where you can get a certification by passing 80 percent of the paper. If there is any non-conformity, the auditor will issue a major or minor non-conformity that must be closed.

"For example, the forest manager will receive a major non-conformity if it is found that a tree was felled in the riparian buffer zone in the forest, and will not be certified if they can't avoid future recurrence and carry out remedial action," he explained.

Currently, only Kelantan, Malacca, Perlis and Penang in the peninsula are not MTCS-certified FMU. Kelantan lost its certification in 2016, after converting more than five percent of its primary forest to other use.

Forest plantations certified, too

Despite MTCS’s stringent requirements, some legal forest management practices may still fall short of its criteria.

For example, states still have the right to convert natural forests into forest plantations. However, they can lose the certification if the conversion process and maintenance are substandard, or they breach the five percent threshold.

Timber from the first round of clearing will also not be certified under MTCS, but subsequent harvests from timber plantations set up on that cleared plot can be.

Forest plantations, largely opposed by environmentalists, are also certified by MTCS. There are 10 forest plantations which are MTCS certified, making up more than 143,000ha.

In addition, even if a state is certified, that does not mean that all legally harvested timber in that state would be COC-certified under MTCS.

Once an audit finds noncompliance, the certification is temporarily withdrawn until the problem is fixed.

High-profile case in Baram and beyond

The standards for MTCS may seem strict, but complaints from Orang Asli about encroachment on ancestral or customary lands by the logging industry continue.

The most high-profile case is that of the Penans in Baram, Sarawak, who have filed complaints against MTCS-holder and timber giant Samling for what they say is encroachment into their ancestral land.

Denying this, Samling has taken its detractors to court over their claims, while the MTCS dispute resolution process is on hold pending the trial. But the global campaign by the Penan and supporting NGOs on the matter has put a dent in MTCS’ reputation.

Earlier this year, Sarawak Penans travelled to London to demand a halt to the import of MTCs-certified timber, claiming the so-called “sustainable” certification was merely a "greenwashing" scheme.

What is the solution?

One of the biggest sticking points is meeting the conditions of FPIC in cases of dispute among indigenous communities.

Although MTCS guidelines only require auditors to conduct interviews with 10 percent sampling of households, auditors have conducted interviews with all households in the face of dispute in Baram.

But this is not always possible in every case, an MTCC representative told Malaysiakini.

He added that since the land issue is under the jurisdiction of the state governments, MTCS will continue facing the same issue.

“People tend to think companies are bad guys, but how do they conduct this (FPIC) ethic?

“When (the auditor) goes to the village, maybe the people are not able to show up (for engagement). We’re not the Election Commission; we don't go around and take votes.

“Even within a family, every child will have different opinions about what to eat for dinner. Some want pizza, some prefer sushi. We’re in this situation and I don’t have any solution.

“MTCS stands by the FPIC principle. You can say we’re not doing enough, but what is the solution? We are just a tool (to achieve the goal), and the goal is sustainable forest management," said the representative.

‘Don't abandon forest certification’

MTCC is worried that the Baram public relations crisis will lead to total rejection of the scheme, something it believes will bring more harm to Malaysia’s forestry management practices.

"We’re concerned. By doing this, they are just throwing the baby out with the bathwater. We hope this is just a misunderstanding. Please don’t abandon the certification,” an MTCC representative said.

He said without the MTCS, there won’t be a third party monitoring the forest managers. Without auditors, even laws could be broken without anyone knowing.

“They want to discredit us, saying that we are not enough. But when you look at Kelantan, some NGOs want to complain to the auditor or us, but we cannot do anything since they are not certified anymore.

“They depend solely on the State Forestry Department to process their grievances. Certification provides a platform to allow stakeholders to actually express their concern,” he said.

Sirim sidesteps questions

Both the Perak and the Baram logging projects were audited by Sirim. When contacted, Sirim chose not to respond to specific questions on the projects, nor claims that it was not conducting audits fairly and is engaged in “greenwashing’.

It also chose not to provide information on the number of complaints it received and how much it charges for an audit. However, in a statement to Malaysiakini, certification senior general manager Mohd Hamim Imam Mustain urged stakeholders to lodge complaints to forest managers through their dispute resolution mechanism.

He said forest managers have to establish dispute resolution mechanisms, in order to get MTCS certification, and the community should use this to raise their grievances.

He also urged stakeholders to send a copy of their complaint to forest managers, to Sirim QAS International so it could be looked into during surveillance audits.

What is Orang Asli land?

Hamim also stressed that the term “customary land” for Orang Asli does not exist under the Aboriginal Peoples Act 1954.

Under this act, the Orang Asli have rights to access the forest and collect forest resources for their own consumption but not for commercial purposes. The law also allows Jakoa to resettle villagers while the state government has the right to revoke Orang Asli reserve status without due compensation or allotting replacement land.

In contrast, land laws in Sabah and Sarawak do recognise the rights of native customary land (NCR). But the state can also acquire it and remove the NCR status with compensation. The vulnerable land right status has pushed the Orang Asli to use other means to stake their claim on ancestral land.

This includes using geolocation markers to draw boundaries of their ancestral land and requesting Jakoa to recognise these community maps.

Some have even won through legal channels.

In 2015, the Ipoh High Court ruled in favour of the Orang Asli from Kampung Kuala Senta, Bidor and recognised the community map which was provided by the locals.

Following the ruling, the Perak state government was ordered to gazette 2,209ha of land as native reserve land and revoke the title issued to a company.

The landmark ruling offers a glimmer of hope for the peninsula's indigenous people.

‘Biggest issue is complaints procedure’

Samuel is a Perak activist, who is currently working with a group of Orang Asli from Simpang Pulai to map their ancestral land, as part of Gabungan Operasi Pemetaan, Penyelidikan & Pembangunan Komuniti (GOP).

GOP is a coalition of environmental and Orang Asli NGOs. Samuel is not his real name, but he spoke to Malaysiakini on condition of anonymity, for fear of backlash, which may interfere with his work with the Orang Asli.

The group in Simpang Pulai are preparing a map and documenting their history, culture, and beliefs. The mapping project is expected to take a year and will later be submitted to Jakoa for recognition of their land rights.

His work with GOP and the Orang Asli has shown him that while MTCS can help promote sustainable forest management, it has its drawbacks. The biggest problem, he said, is the frequency of reviews and efficiency of the complaint and investigation process.

Further, he discovered that some of the timber from Perak does not merely come from selective logging projects, but from clearing to make way for Musang King durian plantation or quarry mining.

This approach may help loggers and developers bypass sustainable certifications such as MTCS or RSPO and other regulations, as well as diversify the profit sources, he said.

“(It’s preferred) because it's a lesser hassle compared to timber logging. Perhaps there might be some regulations in the future for Musang King or whatever, but by that time, they will change the game,” he said.

A trust issue

This is a challenge for sustainable certification like the MTCS, on top of the trust issue among indigenous communities.

Having bitter experience with loggers before, Mat Seri does not see how logging - sustainable or not - can benefit the Orang Asli.

"If the (logging) location is very high, how can we accept it? This poses a risk to downstream residents, including landslides, sliding wood and stones, and muddy floods.

“You can't predict these things. It’s just a matter of time," said the 50-year-old man, whose village is located on an elevation.

"We have logging plans, Perak Hydro project, plantations, all sorts of developments on the hills here that are dangerous for people downstream.

"Look at the Pos Dipang flood in 1996, several of my friends died," he said, referring to another Orang Asli settlement in Perak.

‘Selective logging not that green’

The timber industry argues that selective logging is a more sustainable way forward. It involves logging a specified number and species of trees and can be certified with MTCS. But this does not sit well with Dahil Yok Chopil, the Tok Batin of Kampung Chang Lama.

This is despite a requirement for forest managers to obtain data on the size and number of trees in the forest before the project starts, to ensure parent trees and endangered plants are protected. Other regulations include directional logging, no logging in riparian buffer zones and so on. After harvesting, replanting must be carried out to ensure sustainability.

“How do you keep a certain type of tree from being logged when you have heavy machinery going into forests?

“To build the logging roads itself is going to sacrifice a lot of plants and herbs that are used by Orang Asli," Dahil said.

Other critics also worry that selective logging may not be as environmentally friendly as expected. The dead wood that remains in the forest will increase carbon emissions as it decomposes.

Although the Peninsula Forestry Policy 2020 said only selective logging is allowed in permanent forest reserves, clear-felling also happens legally.

This is when a part of the permanent forest reserve categorised as a “production forest” is approved for a plantation project - like the Musang King plantations mentioned by Samuel - or for mining. About 61 percent of permanent forest reserves in Peninsular Malaysia are production forests.

‘Logging has never benefited us’

’Be it selective logging or clear-felling, there is no evidence that logging has benefited the local indigenous people, said Orang Asli activist and Kampung Chang Lama resident Tijah Yok Chopil.

“No Orang Asli village has become rich or prosperous after logging. There is no benefit for us at all, no!

"There is only destruction. We no longer have fish and much wildlife left (the jungle). The land and forest resources are destroyed. Landslides may happen at any time.

“Only two or three villagers would benefit (from the job opportunities) if not none at all. What’s the point?” said Tijah.

Thirty years after the first logging project near Kampung Chang Lama, the streams and rivers are still clogged by sand and debris. Some of the streams have completely dried up, making life difficult for half of the households that do not have access to running water.

"The state or the country depends on logging (for income), but not the community. Logging has happened a few times in this area but I still don't have running water.”

‘Greenwashing’ a global issue

With Malaysia exporting RM22.7 billion worth of timber exports in 2021, logging of forest reserves is unlikely to cease.

Exports to high-end markets in Europe may be part of the incentive for the industry and state government to adhere to sustainable forest management. In fact, 73 percent of MTCS-timber is exported to Europe.

But challenges by stakeholders, like the Orang Asli, to raise their grievances to certification scheme operators raise questions over whether sustainable certification schemes truly ensure more sustainable practices or enable existing bad practices.

This is a global issue. Recent coverage by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has shown how auditing systems in sustainability certification schemes the world over have failed to some degree.

Certification bodies have been reported to overlook deforestation, while deficiencies in the system have allowed bad practices to slip through. Former foresters have also shared how the two largest international timber certification body, Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the PEFC, have diluted their standards and practices.

Instead of setting effective and strict standards, the foresters said, the schemes are now just used by companies as part of a branding exercise where they can pay to look green.

‘Look at Enron’

PEFC, which endorses the MTCS, said its credibility and that of other certification systems have been assessed multiple times and are recognised by the United Nations.

Its communications head, Thorsten Arndt, told the ICIJ, PEFC revises its standards based on “the latest scientific knowledge, research and relevant emerging issues”, and does so along with indigenous communities, trade unions and other non-industry actors.

A spokesperson of FSC, meanwhile, said the certification body has a governance system that engages with stakeholders and has implemented strict environmental rules - a statement which coincides with MTCS’.

At a briefing in Kuala Lumpur recently, FSC Malaysia country manager Charmine Chee was asked if the sustainability certification system is failing.

Speaking in a personal capacity, she admitted that “no auditing system is foolproof or 100 percent perfect”. But she said there have been many examples where adopting FSC standards has improved environmental outcomes, from raising the number of leopards in South America to improving the health of smallholding rubber farmers in Thailand.

“Relating back to accounting and finance, we have all sorts of accounting and financial standards and yet we have cases of Enron. Is the system failing? Not really, it works for most.” - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.