While Parliament’s recent decision to abolish the mandatory death penalty may have come as a surprise, this was the culmination of the work of five successive governments.

Putrajaya first softened its position on the death penalty following widespread outcry over the case of Yong Vui Kong - a Sabahan youth who was on death row in Singapore for drug trafficking in 2007.

Then minister in the Prime Minister’s Department in charge of legal affairs Nazri Abdul Aziz spoke against the death penalty, bolstering an already active civil society campaign for clemency.

Eventually, after four years and in a very rare move, Singapore’s justice system commuted Yong’s sentence to life imprisonment.

By 2017, the Najib Abdul Razak administration amended Section 39B of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 to allow courts discretion to decide whether to impose the death penalty or life imprisonment for drug offences.

Before this amendment, possession of a certain amount of drugs will automatically be considered trafficking which carried a mandatory death sentence. At the time, the minister in charge of law was Azalina Othman Said.

First attempts at abolition

Veteran human rights activist Dobby Chew explained that the government initiated a study on amending death penalty laws in 2013 after calls for abolition were made by lawyers and several human rights groups.

The exact motivation behind the government’s sudden interest in the matter remained unclear. However, Chew noted that it happened around the time Singapore amended its Misuse of Drugs Act 1973 as well as Yong’s sentencing.

“No one knows (why) because everything was done behind closed doors, but the start of the review happened around the same time the news of Yong Vui Kong broke,” said Chew, who is the executive coordinator of Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (Adpan).

“The earlier discussion had galvanised groups to push for abolition, led by Amnesty International Malaysia and the Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (KLSCAH) civil rights committee.

“(It was also) supported by groups of lawyers, Adpan, Suaram, and many others,” he told Malaysiakini.

Legislative work on death penalty reforms took off in earnest during the Dr Mahathir Mohamad administration in 2018, which had to fulfil Pakatan Harapan’s election pledge to abolish “mandatory death by hanging in all” federal laws.

Then law minister Liew Vui Keong planned to table bills to amend relevant laws by Oct 15, 2018, and announced a moratorium on all executions pending the passage of the amendments.

At the time, the Mahathir administration explored the possibility of total abolition but this was met with strong opposition, primarily by families of murder victims.

Following this, Putrajaya set up a committee to study the repeal of the mandatory death penalty for 11 out of 33 related criminal offences.

The government cited public concern, but Chew felt Harapan was not fully prepared to deal with naysayers.

“Backlash happened and Harapan didn’t have the experience and depth of knowledge to make stronger counterarguments. (It) got overwhelmed.

“So the government backtracked and decided to take the middle ground of abolishing the mandatory death penalty, placating the victims’ families with something that abolitionists can still accept and support,” Chew explained.

Eventually, the Mahathir administration never managed to table any bills of such nature as their tenure in government ended in February 2020.

An impermanent hope

The subsequent Muhyiddin Yassin cabinet pledged to study the report of the committee set up by the previous administration on the abolishment of the mandatory death penalty.

When then-law minister Takiyuddin Hassan was quizzed in November 2020 in Parliament on the position of the Muhyiddin administration on the death penalty, he was non-committal on the matter.

By 2021, discussions on the death penalty resurfaced following the outcry on the imminent execution of Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, a Malaysian, in Singapore for drug trafficking.

Former prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob and former foreign affairs minister Saifuddin Abdullah penned letters to their Singaporean counterparts to consider granting Nagaenthran clemency.

Public clamour grew louder after his execution in April last year, despite calls for change from around the world, including from EU representatives and figures such as British magnate Richard Branson.

Soon, ministers and MPs were debating the death penalty in the august House once again. Nazri, as then Padang Rengas MP, even renewed his call for abolishment.

The following year, former law minister Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar said the Ismail Sabri administration agreed to abolish the mandatory death penalty with expectations that the necessary amendments would be tabled last October.

Unfortunately, the Parliament was dissolved before the bill could be tabled.

More work to do

Following the formation of Anwar Ibrahim’s government, Azalina is the law minister once again, with Jelutong MP Ramkarpal Singh as her deputy.

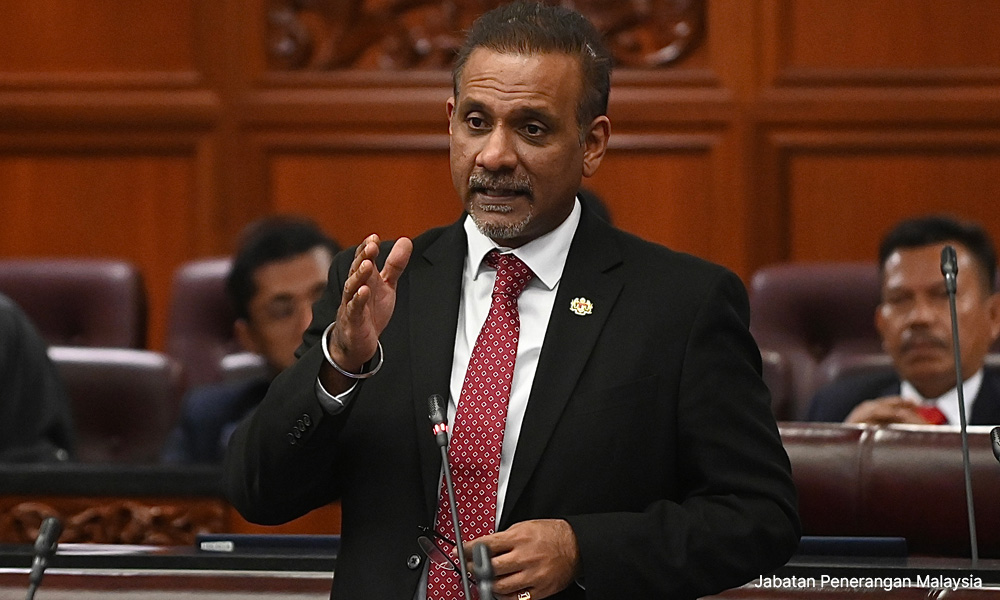

Azalina delegated the Revision of Sentence of Death and Imprisonment for Natural Life (Temporary Jurisdiction of the Federal Court) Bill 2023 to Ramkarpal, who oversaw the passing of the bill on Monday (April 3), barely six months after the new government took office.

The new laws do not eliminate the death penalty altogether but will instead allow judges to use their discretion in imposing penalties that are proportionate to the crime that was committed, up to and including the death penalty, where necessary.

Chew, who had long been advocating for the law’s reform, said that while the bill was passed, the journey is far from its end.

He said the government will have to work with lawyers and families in identifying cases, as well as engage with other stakeholders such as the judiciary and Prison Department, to establish a new appeal process.

Chew also noted that the methodology behind the mitigation hearing will have significant consequences moving forward, not just for those currently on death row.

Further, he said there will be some who disagree with this move, and so he commended the deputy minister for taking it one step at a time, starting by removing the mandatory sentencing.

He added that with support and advocacy, the public can have a better understanding and appreciation for rehabilitation and restorative justice, and why abolitionists oppose the death penalty outright.

“There needs to be some degree of buy-in and support from the public, and abolishing the mandatory sentence will get us there,” he added. - Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.