The big boys have gathered to protect their turf and lecture the government on how they want to conduct their business in Malaysia.

They are telling us how and what we should legislate and how we should enforce the law and want the government to halt its plan to impose licences on social media platforms, saying the plan was “unworkable”.

Who are they, exactly? A group of companies, some of which have no recognised representation in the country, think they know best what is good for Malaysia and its people.

The Asia Internet Coalition (AIC), representing tech giants including Google, Meta, and Amazon, voiced its objections in a letter to Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim dated Aug 23.

Among the issues raised was that social media and messaging platforms covered areas of self-regulation, consultation and limiting their liability against criminal sanctions.

It also wants the government to remove any provisions that would impose criminal liability on service providers and representatives and instead create “safe harbour” protections to limit their liability from user-generated content.

If third-party representatives are appointed to front RM2 shell companies, they will be thrown under the bus in case of trouble. Millions in revenue would have been repatriated by then.

Every country does it differently

Why should the government limit its liability? In the past, Malaysian media companies and individuals have paid heavily for their indiscretions, and some of them have gone to jail, albeit using some of these platforms.

There was no hue and cry or appeals to the UK government from their European counterparts when the Online Safety Bill was passed, yet a requirement for registration has brought about such a blatant protest.

The AIC argued that the UK regulates online services under its local laws without the need for a “formal and cumbersome” licensing procedure.

Agreed, but every country has reasons for doing it differently. And AIC should not be dictating how Malaysia must go about it.

But be reminded that Malaysia’s own legislation, which we have been told, is on the same lines as the one in the UK, is being drawn up.

At this point, it has to be pointed out that the UK’s Online Safety Act has created a new concept in the duty of care of online platforms, requiring them to take action against illegal, or legal but “harmful” content from their users.

Platforms failing this duty would be liable to fines of up to £18 million or 10 percent of their annual turnover, whichever is higher.

While these companies are willing to be subjected to heavy penalties elsewhere, they have the cheek to demand limitation of liability here.

Reckless to allow self-regulation

Instead of imposing a licensing regime, the AIC wants the government to consider a self-regulation model like New Zealand’s Code of Practice for Online Safety and Harms.

But self-regulation has not worked. For the past three decades, Malaysia practised this, but sad to say, each company’s values, morals, and ethics differ and the imposition of penalties has been selective.

Each has its own set of rules and regulations, and it would be reckless to allow such a practice.

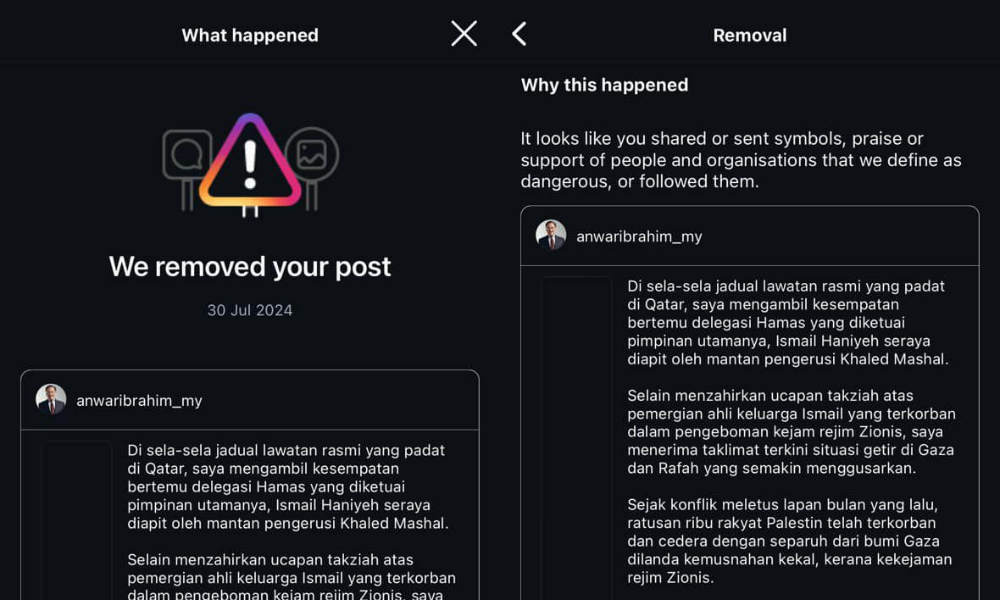

Remember the episode of the removal of content featuring Anwar?

Meta’s removal notification from Instagram stated that the post contained “symbols, praise, or support of people and organisations that we define as dangerous”.

The posts were restored but included a footnote that they are still in violation of Meta’s community guidelines.

It was the so-called self-regulation that was at work. But then it must also be said that some platforms have refused to remove content on request from the authorities because “we don’t see them as harmful”.

‘No formal consultation’

The AIC claimed there were no formal public discussions before the government published the legislation’s guidelines on Aug 1.

This, AIC said, created a “great deal” of uncertainty among platforms on what they would be signing up for.

“No platform can be expected to register under these conditions,” the coalition’s managing director Jeff Paine added.

Consultation? Is that new or novel to AIC?

Last night, ride-hailing and food delivery firm Grab, which was listed in the protest letter, distanced itself from the statement.

Grab Malaysia said: “The proposed regulation does not impact our operations, and therefore, we had no part in it (the letter). We remain committed to collaborating with the government, reflecting our mission to contribute to the nation’s development.”

The AIC also warned that the licensing scheme could increase regulatory uncertainty and impact Malaysia’s economy without significantly reducing harmful online content.

It is a warning Malaysia can choose to ignore. We promulgated many laws that may be seen in a different light, but we have a right to prioritise people’s safety and welfare over everything else.

The same warnings loomed in 2021 when Australia was drafting laws to make it mandatory to require tech giants such as Google and Facebook to pay local media for reusing their content.

Google Australia and New Zealand managing director Mel Silva said the code would severely impact Google and its subsidiary YouTube.

“…the proposed law would force us to provide you with a dramatically worse Google Search and YouTube, could lead to your data being handed over to big news businesses, and would put the free services you use at risk in Australia.

“The law would force us to give an unfair advantage to one group of businesses - news media businesses - over everyone else who has a website, YouTube channel, or small business,” she said, but that threat was dismissed.

Licensing can trace wrongdoers

The AIC must understand that to do business in Malaysia, every entity must be registered as a business or a company and comply with all related laws, rules, and regulations.

Such a requirement is simple. If a breach occurs, the authorities can trace the wrongdoers and take appropriate action.

These companies want a world with their own laws, refusing to comply with what is legislated. They do not want to be controlled, answerable, or responsible for their actions and inaction.

They should never be allowed to do so by shouting us down, threatening or insinuating that what we plan to do for the good of people is not workable. - Mkini

R NADESWARAN is a veteran journalist who writes on bread-and-butter issues. Comments: citizen.nades22@gmail.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.