As the biggest kleptocracy in the world, where the scale of corruption in Malaysia goes into tens of billions of ringgit, it is a shock that the MACC actually finds it a shock that the country's anti-corruption ranking has regressed to 62nd place.

Indeed, as DAP veteran Lim Kit Siang has pointed out, between 2009-2018, Malaysia's rankings under Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak have never improved one bit.

Granted that the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is partly based on the responses of businesspeople, what is actually deemed a "perception" is, in fact, a reflection of their experiences, and encounter with endemic practices and their entrenched roles in the system.

Even if these businesspeople prefer to extricate themselves from the insidious practice of averting and avoiding corruption altogether, they may find themselves unable to challenge the status quo.

A broken protection system

There are three reasons. To begin with, the whistleblower protection system is practically broken and beyond redemption under the current regime.

When Pandan MP, the affable Rafizi Ramli, spoke out against corruption in the National Feedlot Corporation, he was sentenced to 30 months in prison, ostensibly for breaching the Banking Financial Information Act (Bafia).

A fellow whistleblower, one Johari Mohamad, also found himself being implicated by the Malaysian courts. While both are now appealing against their sentences, the damage to them has been done. Rafizi, despite his exceptional efforts, for instance, cannot run for office lest he wins his appeal.

The unfair treatment of Rafizi (photo) is an example of one of the reasons why Malaysia did so poorly in the CPI.

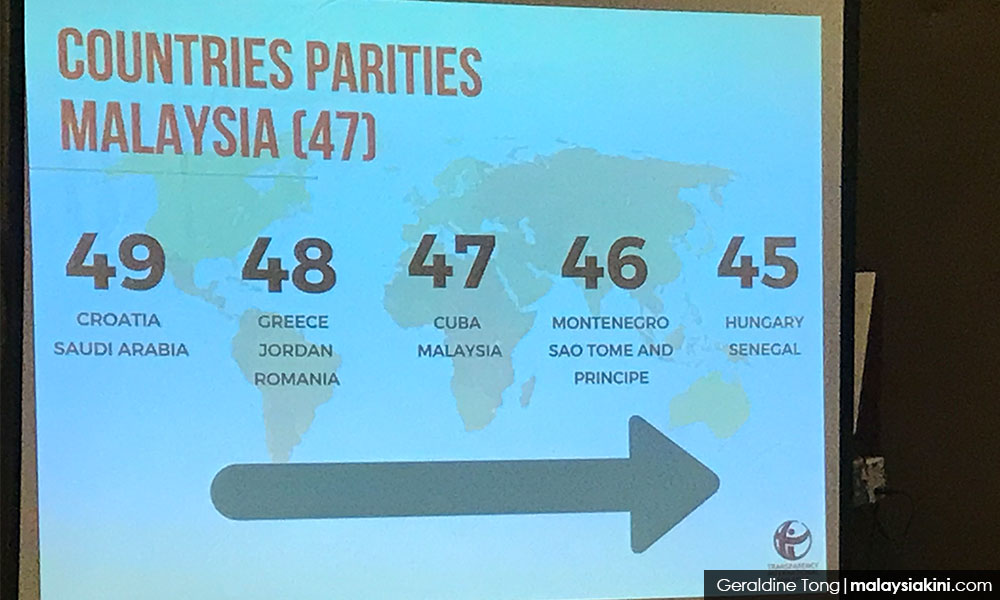

As noted, Malaysia ranked 62 among 180 countries in the CPI last year, dropping from 55th spot in 2016. That is a drop of seven places in a year!

The index put Malaysia in the same spot as Cuba, with a score of 47 out of 100. In 2016, Malaysia ranked 55 with a score of 49.

But this is also the rub: by consistently scoring below 50, between 2016-2017, Malaysia now belongs to two-thirds of the 180 countries that cannot pull itself up by its bootstraps with regard to corruption.

Contrary to what Najib may have said at the Invest Malaysia Conference in February 2018, Malaysia is in fact reeling.

Yet, the Prime Minister's Office has seen it fit to call for the enactment of fake news legislation, when in fact the falsehoods are being peddled from and by the very top in the regime.

If anything, the tenure of Najib says it all - as this is the "worst score in the last five years and the lowest ranking since the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International (TI) was introduced in Malaysia", according to TI Malaysia.

Lack of independence

Secondly, MACC is not a body that operates independently from the Prime Minister's Office, unlike the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) in Hong Kong. Thus, when the prime minister is in the thick of many alleged corruption scandals, such as 1MDB, SRC International, Felda, Felcra and Mara, it goes without saying that the rot will afflict the whole system.

Take the very fact that while the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and various international jurisdictions have found 1MDB to be consumed by corruption and money laundering, not a single culprit in Malaysia has been charged by the MACC or the attorney-general's (AG) office. In fact, the then attorney-general Gani Patail (photo) found himself being removed from the AG's chamber under bizarre circumstances.

His successor Mohamed Apandi Ali has done nothing to either unseal the corruption findings of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) or call for their release, let alone work with the US, Singapore, Hong Kong and Switzerland, despite the Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) sought by the respective foreign jurisdictions.

Absence of political financing laws

Thirdly, the erosion of Malaysia’s status in the CPI is also due to the absence of any political financing laws.

When politicians of all stripes can make use of questionable sources of funding, either through criminal syndicates or organised racketeering, then the lack of any transparency will make the state liable to capture by the criminal underworld, if not the unscrupulous politicians themselves.

To be sure, Professor Edmund Terence Gomez, one of the leading authorities of Malaysia at Universiti Malaya, has spoken consistently of the need for a transparent political donation law.

Yet, his voice and that of Cynthia Gabriel (photo), the chairperson of the Center to Combat Corruption & Cronyism (C4), a non-governmental organisation (NGO), have found themselves being completely marginalised; as is the case of the electoral watchdogs Bersih and Tindak Malaysia.

Indeed, on the day when the findings of the CPI were announced, the prime minister himself did not express any concern. Neither did any members of his cabinet. Their cavalier attitude says it all: They don't care two hoots about the disease afflicting the country.

But they must, and should, care. If not, Pakatan Harapan will be impelled to take the lead. This is precisely due to the interconnectivity of the CPI with the Consumer Price Index.

The latter, to be sure, has a 33 percent weightage on food. When the Consumer Price Index in December 2017 stood at 3.5 percent - as was the same figure in December 2016. It goes without saying that the cost of living has officially doubled.

Double whammy

When one factors in the erosion of the value of the Malaysian ringgit, it goes without saying that Malaysian corruption has produced a double whammy.

First, the country is regressing. Second, the people's livelihoods are totally affected, forcing the present generation to leverage on the savings of the previous generation to get by.

The net effect is a country where private household debt has hit 80 percent or more, with many unable to find any financing caught in the bottom 40 (B40) income group, and consigned to receiving handouts and BR1M payments, which can barely last a few days.

More alarmingly, research has shown that Malaysians have had to sacrifice their needs for nutritional food in order to make ends meet. In about 120 rural constituencies across the country, there are considerable pockets of poverty.

Research by Wan Saiful Wan Jan (photo), who has just left the think-tank the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (Ideas), has shown that Umno captured 108 constituencies in 2013. And, traditionally, this has been the bastion of Umno and BN.

Yet, due to grand corruption, the welfare of the 108 rural constituencies has been neglected, unless it is to frontload them with election goodies prior to the general election.

If anything, research by Serdang MP Ong Kian Ming has shown that the Prime Minister's Office keeps getting an ever-larger slice of the development expenditure.

Indeed, of the 16 percent reserved for Malaysia’s development expenditure, another 25 percent has been further corralled and taken away by Najib to beef up his PMO slush fund and budget further.

With such a vapid form of government, and governance, is it any wonder why Malaysia is languishing with two-thirds of the world that is still struggling with corruption and poverty?

RAIS HUSSIN is a supreme council member of Bersatu. He also heads its Policy and Strategy Bureau.- Mkini

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.