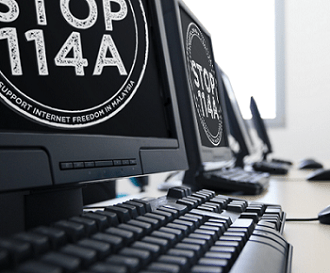

We are pleased to publish a comment by Stephen Mason, editor of the renowned practitioner’s text Electronic Evidence, to the President of the Malaysian Bar, Mr Lim Chee Wee, on his views on section 114A of the Evidence Act 1950, recently introduced by the Evidence (Amendment) (No. 2) Act 2012.

Dear Mr Lim Chee Wee,

In relation to this matter, the new edition of Electronic Evidence (which is published inNovember 2012), includes further materials (especially in chapters 2, 3, 4, and 5) to support your argument relating to the new s. 114A introduced by the Evidence (Amendment) (No. 2) Act 2012.

The legislation in New Zealand has an interesting provision in the Evidence Act 2006 in relation to hearsay, which, arguably, a posting on the Internet must be.

The provisions is as follows:

18 General admissibility of hearsay(1) A hearsay statement is admissible in any proceeding if—(a) the circumstances relating to the statement provide reasonable assurance that the statement is reliable; and(b) either—(i) the maker of the statement is unavailable as a witness; or(ii) the Judge considers that undue expense or delay would be caused if the maker of the statement were required to be a witness.(2) This section is subject to sections 20 and 22.

The necessity to provide a ‘reasonable assurance’ of reliability is of fundamental importance, and ‘circumstances’ is defined under s 16(1) to include consideration of the following questions:

16 Interpretation

(1) In this subpart,—circumstances, in relation to a statement by a person who is not a witness, include—(a) the nature of the statement; and(b) the contents of the statement; and(c) the circumstances that relate to the making of the statement; and(d) any circumstances that relate to the veracity of the person; and(e) any circumstances that relate to the accuracy of the observation of the person

It might be possible to take the New Zealand position on hearsay statements and compare the position. There is reference to case law in the chapter on New Zealand in Electronic Evidence.

In evaluating electronic evidence, subsection 3 to s. 114A is highly significant:

(3) Any person who has in his custody or control any computer on which any publication originates from is presumed to have published or re-published the content of the publication unless the contrary is proved.

The crucial words are ‘in his custody or control’. A person might have a computer or computer like-device in their custody, but the device might not belong to them, and merely being in custody of the device is hardly (unless the circumstances suggest otherwise) a reason to presuming they have written defamatory comments on a web site on the Internet.

Second, ‘control’ is of the utmost significance, which is covered in detail in chapters 2 and 5 ofElectronic Evidence in different ways. I can be using my computer to prepare this document and also use the Internet to send and receive e-mail, and I might think I am in control of the device, but it might be that a third person or persons unknown have gained access to my computer via Trojan horses or another form of malicious software, and might be using my computer and the information associated with my computer and Internet protocol address to be doing things that I am not aware of (a simple example is where people download music or films without paying for them, using the Wi-Fi connection of another person, so the person whose connection is being used is wrongly accused of stealing intellectual property). Again, this is covered in far more detail in Electronic Evidence (with relevant citations of papers and articles) in relation to this matter. It may be that the meaning of ‘control’ will be of significance for lawyers dealing with this issue in the future. To that end, it is important for all lawyers to be educated in the details of computers and how they work, as I indicate in my editorial in theDigital Evidence and Electronic Signature Law Review from 2010.

The significance of s. 114A should not be lost on the politicians.

As my wife and I were leaving Malaysia this summer, I read The Star, dated 24 August 2012. On page 2 was an article written by Edmund Ngo entitled ‘Section 114A stays, says Nazri’. On the page opposite, that is on page 3, was an article entitled ‘I dive, I don’t tweet’ about Pandelela Rinong Pamg, who won a bronze medal in the Olympics in London, and who confirmed she did not have a twitter account, even though a twitter account had been set up in her name.

What would happen to her if a defamatory comment had been posted on the twitter account? Would action have been taken against her? Probably no action, because of her fame, but an ordinary person would have significant difficulties in dealing with the presumption set out in s. 114A in similar circumstances.

Stephen Mason

8 October 2012

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.