Regrettably, it has not been given adequate attention in our school history textbooks.

While the Jesselton Uprising is mentioned in the current Form Four school history textbook (page 79), it, however, does not do justice to the scale and impact of this momentous event which resulted in the tragic deaths of thousands of civilians.

It does not stress a key and unique characteristic of the event - that it was a multi-ethnic revolt.

This omission is unlike the earlier Form Three history textbook first published in 1990 (page 13) which highlighted the inter-ethnic cooperation among the various communities that led to the uprising to resist Japanese rule in Sabah: “Penentangan secara gerila dilakukan oleh semua kaum yang terbesar di Sabah” (Guerrilla resistance was carried out by all the large ethnic communities in Sabah).

Led by Albert Kwok Fen Nam, the Jesselton Uprising hence deserves a special place in our history.

It is the only armed uprising in Malaysia against Japanese rule that was led by civilians comprising various ethnic groups.

As aptly stated by Danny Wong Tze Ken in his book ‘One Crowded Moment of Glory: The Kinabalu Guerrillas and The 1943 Jesselton Uprising’, the revolt “served as an excellent example of inter-ethnic cooperation” in fighting the Japanese.

Calling themselves the Kinabalu Guerrillas and headquartered in Menggatal, Sabahans of diverse ethnic origins participated in and supported the revolt - local Chinese, indigenous communities (Bajaus, Suluks, Dusuns, Muruts, and Binadans), Eurasians (including Charles Peter and Jules Stephens), and Sikhs (Subedar Dewa Singh, Sergeant Budh Singh, and Corporal Sohan Singh).

To top it all off, one of its most flamboyant guerrillas was a Ceylon Tamil, Rajah George Sinnadurai.

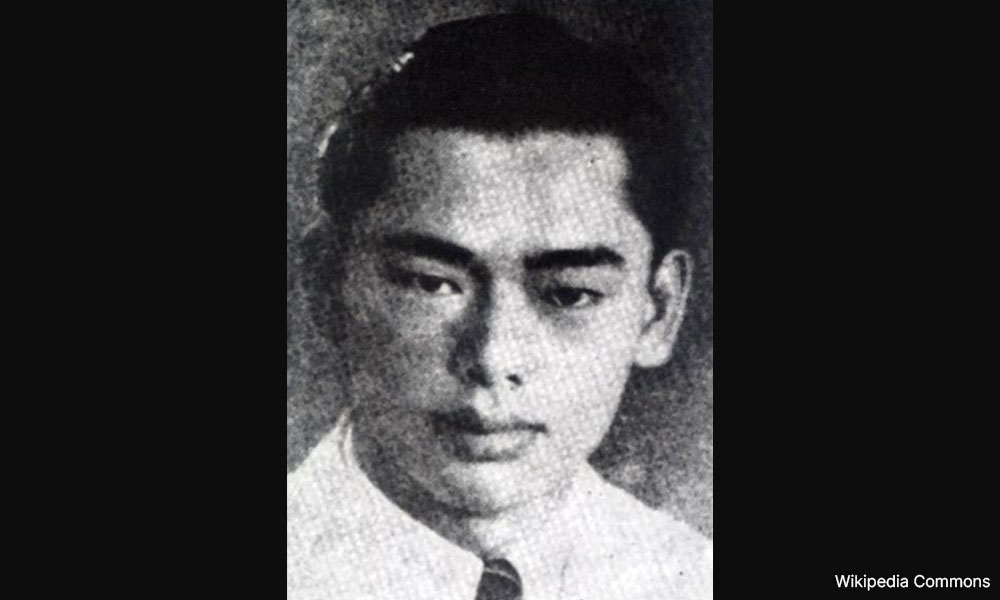

Their leader, Albert Kwok, a young and energetic Kuching-born (1921) Teochew Chinese, was educated in Shanghai, China.

He worked with the China Red Cross and also served under the Kuomintang during the Second Sino-Japanese War 1937‒1945.

Kwok returned to Borneo in late 1940 and moved to Jesselton (present-day Kota Kinabalu) in May 1941 where he started his successful traditional healing practice of treating piles.

Among the leading Kinabalu Guerrillas were Kong Sze Phui, Lim Keng Fatt, Li Tet Phui (a former lieutenant in the North Borneo Volunteer Force), Tsen Tsau Kong, Charles Peter (a former chief police officer), Jules Stephens (a former sergeant in the North Borneo Volunteer Force who served as the Adjutant of the Kinabalu Guerrillas), Duallis (a Murut and former chief inspector of the North Borneo Armed Constabulary), Musah (a Dusun native chief of Membakut), Orang Tua Panglima Ali (a Bajau village chief of Suluk Island), and Orang Tua Arshad of Oudar Island.

By way of historical background, it should be noted that the Jesselton Uprising occurred at the height of the Second World War.

The Japanese conquest of Sabah began with the invasion of Labuan on Jan 1, 1942. Eight days later, they took over Jesselton. By Feb 1, 1942, the Japanese were in full control of Sabah.

During the war, guerrilla groups in the Philippines which were controlled by the Americans extended their influence to Sabah.

Through Lim, a prosperous businessperson, Kwok befriended a Sulu, Imam Marajukim, who was in close contact with Alejandro Suarez, a guerrilla leader in the Philippines. Kwok visited Suarez in early 1943 and learnt about guerrilla warfare techniques.

What caused the uprising

Let’s now delve briefly into the major causes of the 1943 Jesselton Uprising.

During Japanese rule in Sabah, the Chinese community suffered the most. Several Japanese companies seized control of most of the businesses in Sabah which severely affected the Chinese entrepreneurs.

The Japanese also coerced the Chinese to raise funds for Japan’s war efforts. Towards this end, the Jesselton Chinese raised $600,000 while the Sandakan Chinese raised $400,000.

What further angered the Chinese community was that their leaders, who were involved in the China Relief Fund, were arrested by the Japanese and imprisoned in Kuching.

In the case of the other ethnic groups, they were also hugely opposed to Japanese rule in Sabah primarily due to the scarcity of essential foodstuffs (particularly rice), recruitment of conscripted labourers, and forced recruitment of native women to serve as comfort women in Japanese military brothels.

It should be noted that Chinese nationalism also played its part in the outbreak of the revolt due to Japanese atrocities in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Ooi Keat Gin, in his book titled ‘The Japanese Occupation of Borneo, 1941‒1945’, concludes that “the spark of the Kinabalu Uprising of October 1943 was ignited by Chinese nationalism and was fanned by the sufferings of the indigenous communities”.

What apparently hastened and precipitated the outbreak of the Jesselton Uprising was the general belief among the Chinese community that the Japanese were planning to conscript about 3,000 Chinese youths for military service and a large number of Chinese females to serve as comfort women.

No one really knows for sure what was Kwok’s actual plan in leading the revolt. Most likely, as suggested by FG Whelan in his book ‘Stories from Sabah History’, he hoped that his strike against the Japanese at Jesselton would spur other groups to resist Japanese rule.

The attack

He might have further hoped to retreat to his hideout, wait for arms and supplies from Suarez, and subsequently obtain assistance from the Allied forces.

On the night of Oct 9, 1943, the Kinabalu Guerrillas, comprising about 100 Chinese armed mostly with parangs, launched their attack on the Japanese.

The first attack was made on the Tuaran police station. The guerrillas managed to kill four Japanese police personnel and seized six rifles and some ammunition.

The second attack, according to Maxwell Hall in his book titled “Kinabalu Guerrillas: An Account of the Double Tenth 1943”, was made on the Japanese police station at Menggatal. Fifteen Japanese and three native police officers were killed.

Subsequently, the Kinabalu Guerrillas attacked Jesselton at about 10pm. This land attack by the Chinese was supported by a sea force of more than 100 indigenous people (Bajaus, Suluks, Dusuns, and Binadans) who were gathered together by Orang Tua Panglima Ali of Suluk Island.

He was ably assisted by Orang Tua Arshad, Jemalul of Mantanani Island, and Saruddin of Dinawan Island. The islanders attacked the military stations and burnt the Customs sheds hoping to attract the attention of Allied ships in the area – unfortunately, there were none. The whole operation took about three hours.

On Oct 10, 1943 (National Day of the Chinese Republic), the Kinabalu Guerrillas celebrated their glorious, albeit short-lived, victory by parading flags – the Chinese national flag, Sabah Jack, Union Jack, and the Stars and Stripes - on all the major buildings from Jesselton to Tuaran.

Following their initial success, on Oct 12, 1943, a small force of 12 men (the majority of them being Dusuns of Tambunan) under Rajah George Sinnadurai set out to capture Kota Belud.

They ran into three armed Japanese at Tenghilan and managed to kill them, one of whom was Ishikawa, the Jesselton police chief who managed to escape during the earlier attack on the night of Oct 9.

Rajah George then rode in style to Kota Belud town donning Ishikawa’s riding boots and his samurai sword. The four captured Japanese in Kota Belud were executed. All in all, the Kinabalu Guerrillas had killed about 50 Japanese.

The Japanese retaliate… brutally

The Japanese response to the uprising came almost immediately and viciously.

Beginning Oct 13, 1943, the Japanese counter-attacked mercilessly. Coastal villages along the Tuaran road were bombed and machine-gunned, as a result of which about 3,000 civilians were killed indiscriminately.

Japanese troops reoccupied Jesselton. Kwok surrendered on Dec 19, 1943, with the hope that the Japanese would not persecute other Sabahans.

Ten days later, Lim arrived off Sabah’s coast with arms and men from Suarez to assist the Kinabalu Guerrillas. He did not land as Kwok had already surrendered.

Around the end of October 1943, the Japanese attacked Suluk Island, set fire to all the houses and killed all the men.

The women were taken away and forced to work in the rice fields of Bongawan. It should be noted that when the British landed on Suluk Island in 1945, there were no adult males. An 11-year-old boy was the headman.

The Japanese also attacked Oudar Island and massacred 29 people.

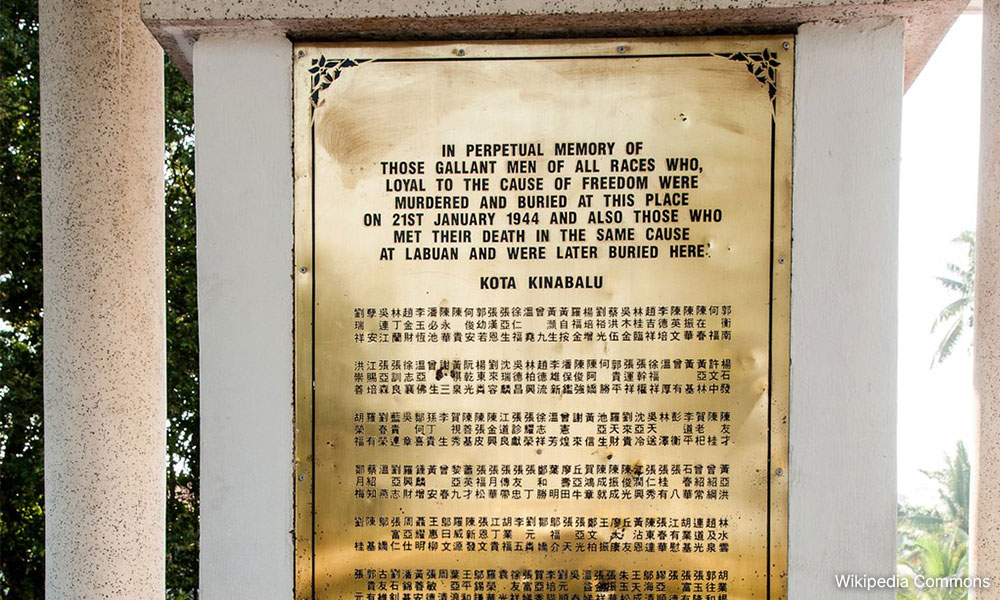

On Jan 21, 1944, Kwok, with 175 others including Kong, Li, Charles, Tsen, Stephens, Panglima Ali, Rajah George, Budh Singh, and Sohan Singh were executed by the Japanese at Petagas.

Another 131 people were imprisoned at Labuan, out of whom only nine remained alive at the time of Sabah’s liberation by Allied forces.

Japanese atrocities did not stop with the Petagas executions. On Feb 11, 1944, the Japanese visited Mantanani Island and arrested 58 Sulus who were taken to Jesselton. Most of them died at the Batu Tiga Prison.

Two days later, the Japanese revisited the island and massacred about 80 people.

It should be noted that Duallis and his Murut followers continued guerrilla warfare against the Japanese until the Allied forces liberated Sabah from Japanese rule.

In recognition of the Kinabalu Guerrillas’ struggle, the Sabah government has built a war memorial at Petagas.

In honour of their sacrifices, an annual remembrance ceremony is held on Jan 21 at the Petagas War Memorial. Additionally, two streets in Sabah are named after Kwok and Li.

To conclude, the multi-ethnic 1943 Jesselton Uprising must be given its rightful place in our school history textbooks.

This was no ordinary resistance. It is a testament to the rare occasion in our history when ordinary Sabahans of different ethnic backgrounds came together for a noble cause.

To paraphrase FG Whelan, hundreds of Sabahans under the heroic leadership of Kwok fought bravely and sacrificed their lives so that others could live in liberty and peace. - Mkini

RANJIT SINGH MALHI is an independent historian who has written 19 books on Malaysian, Asian and world history. He is highly committed to writing an inclusive and truthful history of Malaysia based upon authoritative sources.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.